Ages 6-12 Data, 2020

Data on this page were provided by the Sports and Fitness Industry Association (SFIA), which annually commissions an online, nationally representative survey from Sports Marketing Surveys that tracks sport participation rates. The most recent data collected was at the end of 2020 from 18,000 individuals and offers a snapshot of activities then, placed into historical context.

Below are charts and key findings related to youth ages 6 to 12.

The chart above tells an interesting but nuanced story, shaped by the historic challenges and opportunities presented by COVID-19. Not surprisingly, 2020 produced many data complexities, making it very difficult to compare to previous years.

Overall, more kids played sports in some form but with less intensity, limited by the availability of organized activities. That’s both a promising development given the problem of overuse injuries and other pressures that children at the center of the youth sports industry have faced, and one that gives leaders some pause. In SFIA’s definitions, regular participation in a given sport might constitute playing only a couple dozen days during the year – and that includes casual play activities like kicking a soccer ball with siblings in the park.

“We’re encouraged because the number of participants did not go down as much as it could have,” said Tom Cove, SFIA president and CEO. “People were thirsty for activity and found ways to do some of it. But without question, there’s a massive drop-off in the overall times kids played team sports during the pandemic year.”

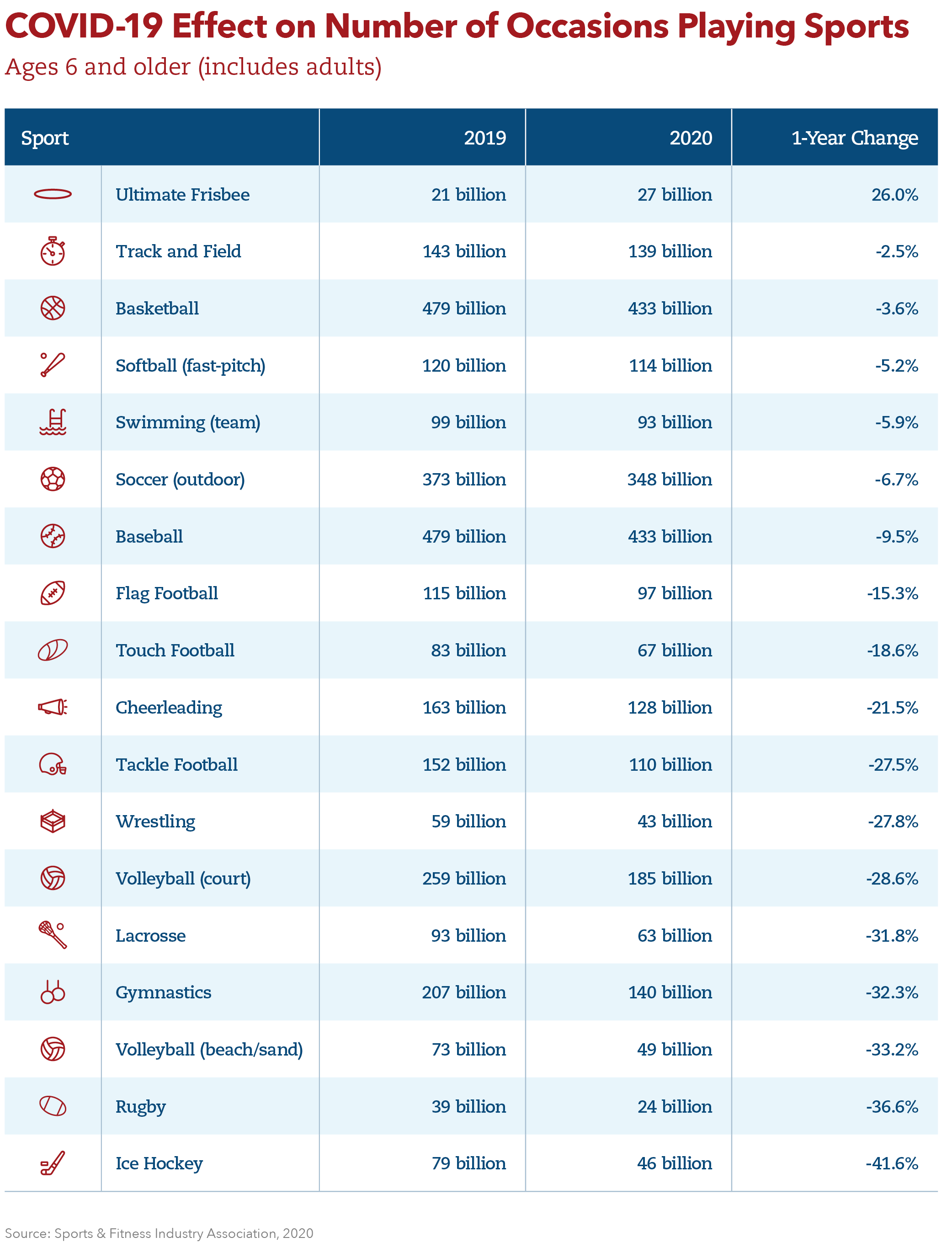

Americans played sports a lot less in 2020. SFIA data has not yet analyzed play occasions data for youth, but these figures for everyone 6 and older suggest what they may look like. Sports that could be played outside, individually and with less contact typically fared better than indoor, team-focused, high-contact sports. Play occasions for Ultimate frisbee were up 26%; play occasions for hockey were down 42%.

Ultimate also benefits from the lack of any need for referees – they aren’t used even in non-pandemic times, as players make the calls. The U.S. faces a national shortage of referees. Fewer people want the low pay and increasing verbal – and sometimes even physical – abuse directed at refs by some coaches and fans.

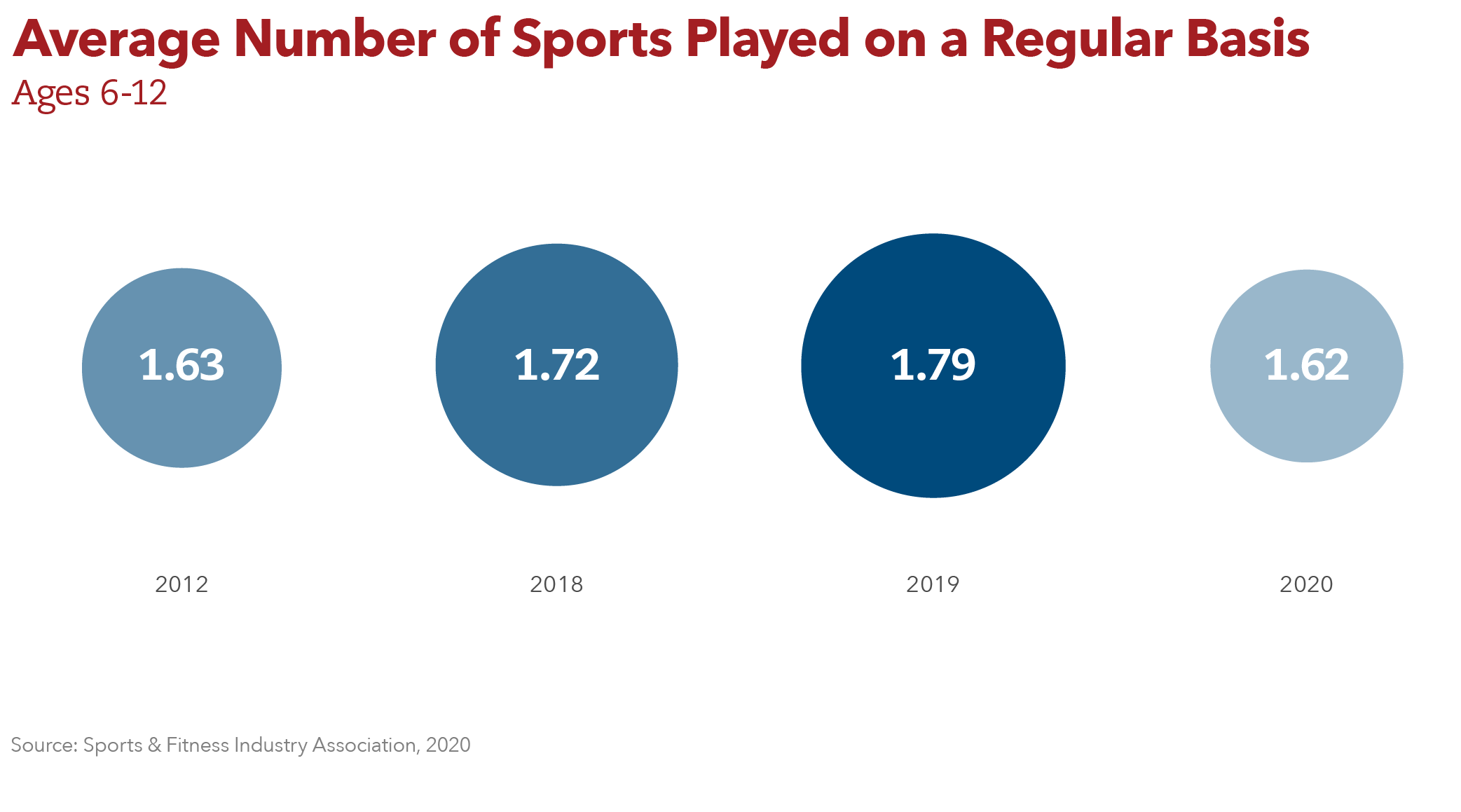

Not surprisingly, the average number of sports played by a kid on a regular basis declined in 2020. Shutdowns and school closures meant fewer opportunities to play organized sports. The total number of sports played (not counting how often the child played) decreased at a lower rate. Project Play used a chart reflecting play on a regular basis this year to show much less children participated in sports during 2020.

Soccer suffered mightily during the pandemic. Usually one of the most popular sports for kids ages 6-12, soccer had only 73,000 more participants than tennis and 226,000 more than golf. That would have been unheard of in a normal year. In 2019, soccer had 967,000 more kids than tennis and 916,000 more than golf.

Individual, outdoor sports fared the best during a tough year to generate regular participation for most sports. Twelve of the 17 sports analyzed by Project Play experienced participation declines. Only basketball, bicycling, golf, tennis and track and field grew participants at this age since many other sports were shut down or faced restrictions.

“Over the course of the year, people reimagined team play with informal practices, small numbers of kids at practices, and trainings more than games,” Cove said. “The nature of your team really influenced this. If your access to team sports was entry-level and park and rec teams, your participation probably dropped off dramatically. Travel-level teams had an already-organized structure with a coach who could communicate trust and get people together for practices. You didn’t get that at the entry level because volunteer moms and dads weren’t able to do that.”

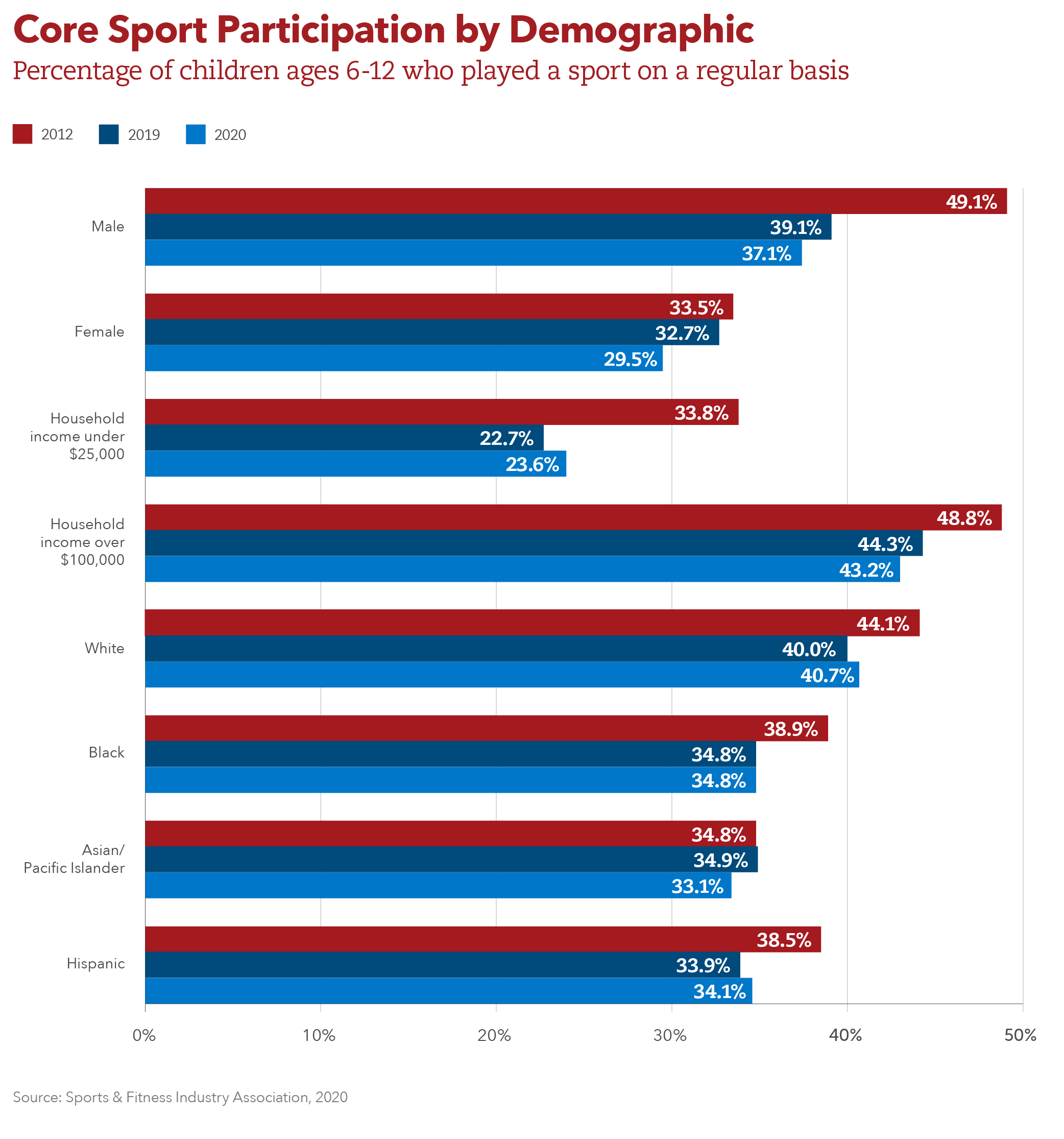

The SFIA data showed a rare increase in regular sports participation by kids in homes making $25,000 or less. It’s not clear exactly why that happened, especially with local, low-cost programs struggling the most to restart play. This much, we know: Playing sports on a regular basis in 2020 typically meant more informal play than organized teams.

“There was a certain democratization of activity in the pandemic year,” Cove said. “You didn’t have to pay big fees to play. Money didn’t protect you from COVID and didn’t keep leagues and venues open. So, if you moved to more informal play, this makes sense. The gap (with high-income families) is still too high. But it’s a lesson we could appreciate: If we could make sports more accessible and less costly, it’s likely we could close the activity gap by income level.”

There remained a gap in participation based on race and ethnicity. White youth ages 6-12 (41%) were more likely to regularly play sports than Black (35%), Hispanic (34%) and Asian (33%) children.

“Organizations must address the economics behind play,” said Nichol Whiteman, CEO of the Los Angeles Dodgers Foundation. “Even if a program covers the full cost of participation, we must provide the supplemental support that many families need in order for their child to engage. Do Black and Hispanic families in underserved communities have the transportation resources that allow their children to travel from school to activities? Many families do not have the luxury of flexible schedules, thereby making it more difficult for their children to engage in extracurricular activities. Coupled with the fact that even older elementary school youth may play a role in caring for younger siblings, an effective strategy will include wrap-around services for the entire family.”

"If we could make sports more accessible and less costly, it’s likely we could close the activity gap by income level.”

— Tom Cove, Sports & Fitness Industry Association CEO

No sport fared better in 2020 at adding and retaining kids as participants than basketball. Basketball’s strength during a pandemic is it can be played outside and in small numbers, or even individually. Some communities initially closed outdoor basketball courts during the early months of COVID-19, but later reopened them as a way for kids to be physically active and enjoy themselves. The virus is more transmissible indoors, meaning indoor sports like gymnastics and volleyball struggled much more to add and retain children.

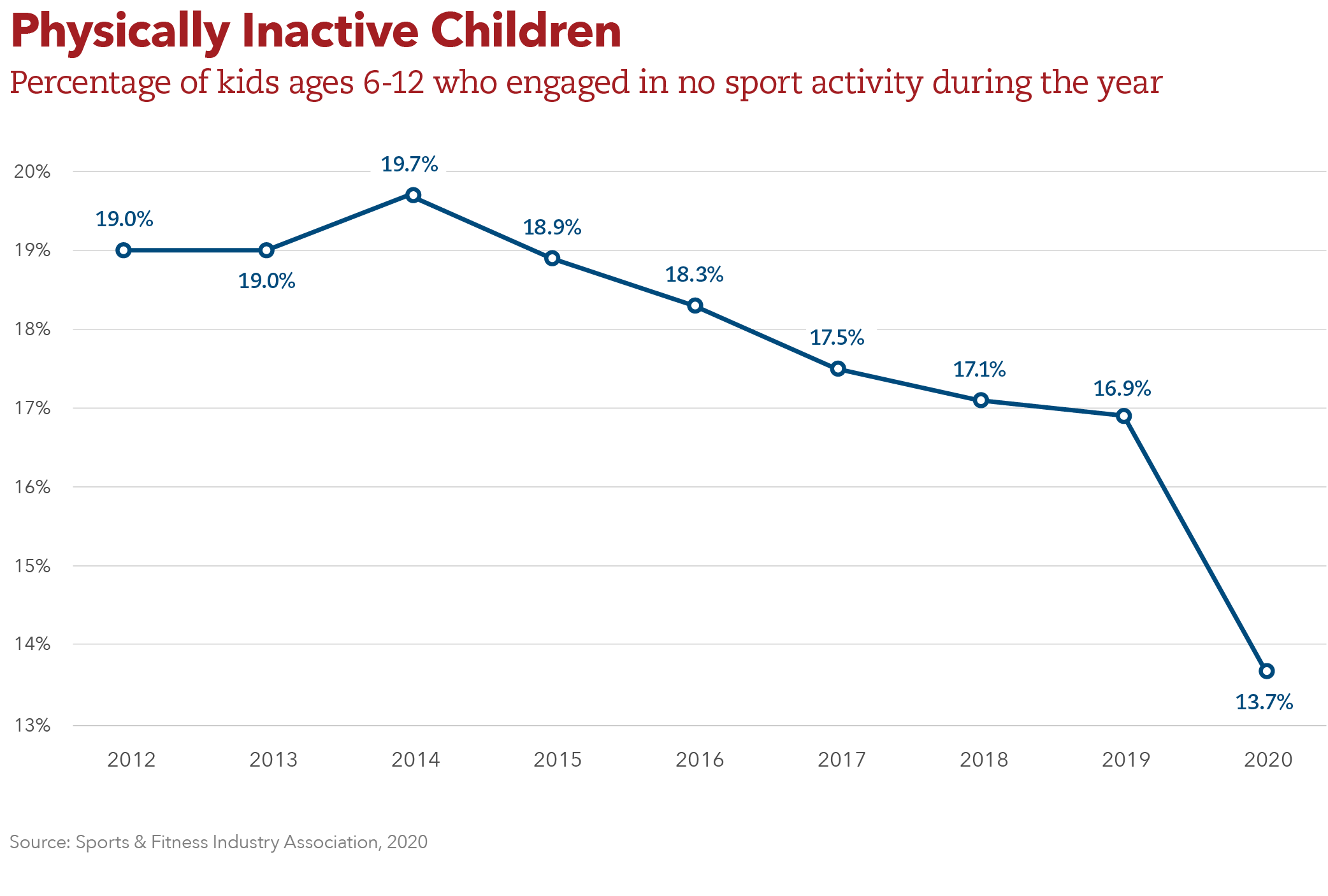

Good news from 2020: More kids did something physically active. This statistic on physical inactivity measures the percentage of children who engaged in no sport activity. Activities such as archery, camping, fishing, jet skiing and target shooting count as being physically inactive. This statistic had been trending positively before COVID-19, but it never saw a one-year improvement like 2020. Adults and children recognize the importance of being active.

“Some of the conversations around Project Play’s strategies of local, informal free play, and other long-term policy goals, opened up in one year more than what 10 years of advocacy could do,” Cove said. “We’re at an inflection moment of sports in America. Will we take some of the love of sport and thirst for activity and build on it to get more participating? And will we learn from the pandemic-induced changes to the way we deliver sports and make the experience a little more reasonable and family friendly?”

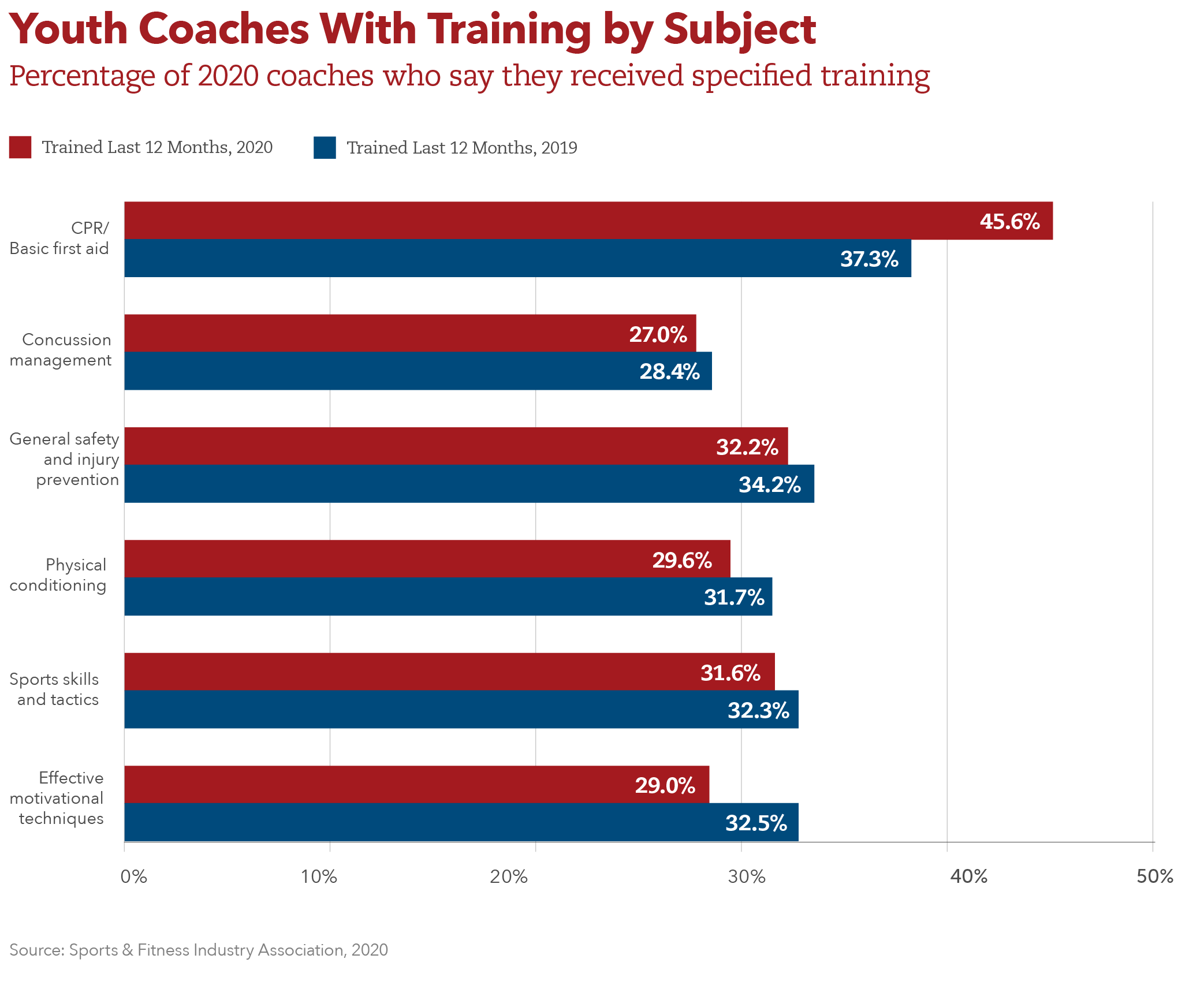

Disappointing news from 2020: More coaches didn’t take the time off from sports to get trained. Every training category except CPR/basic first aid saw a lower rate of training by coaches in 2020 compared to a year earlier.

“We were thinking this would be a good year for coach training,” Cove said. “There wasn’t organized sports, so people weren’t thinking about it and had no impetus or requirement to act.”

Less than half of youth sports coaches were trained to deliver CPR/first aid, only one-third received training in injury prevention or physical conditioning, and only a quarter were trained to manage concussions. In 2019, CDC reported that youth sports injuries result in nearly 3 million visits to emergency departments each year.

“While parents see sports participation as an opportunity to improve their children’s health, most youth sports coaches are not adequately prepared to meet these expectations,” said Joe Janosky, director of injury prevention programs at Hospital for Special Surgery. “Sports medicine experts and youth sports organizations should be collaborating, at both the national and local level, to provide cost-effective training for coaches that promote children’s health and safety because the health risks associated with sports participation for children should never outweigh the benefits.”