THE PROBLEM

Principals and school leaders today are tasked with developing the whole student. Many appreciate that sports,+ broadly defined to include all forms of physical activity, can help students grow academically, socially, physically and mentally in ways that will benefit them throughout their lives. Sports are a meaningful strategy to foster student engagement and motivation, which so many states, districts and schools are grappling with now.

In fact, sports are the best venue in schools to build social and emotional skills,+ according to former U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan.¹ “It’s hard to teach that in Biology. It’s hard to teach that in Algebra,” Duncan said at an Aspen Institute event. “It is much more organic and authentic to do it through sports. It’s the perfect practice field for those skills.”

Yet, fewer than 4 in 10 students play sports in public high schools² and only 23% get the recommended level of daily physical activity – down from 29% in 2011.³ Data from the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) also show a decline in total sports participation opportunities.⁴ Many high schools are unable to deliver sports programs that meet the needs and hopes of students.

HIGH SCHOOLS LACK THREE TYPES OF SUPPORT:

FUNDING

Athletic departments do a lot with a little. In the national search for innovative high schools that anchored this project, the winning schools typically allocated just 2%-4% of the total school budget to sports. Only one winner surpassed that, a small suburban school that spent 10% by spending heavily in football, the most expensive sport. Coaching stipends, equipment, uniforms, transportation, and referees/officials are often the largest expenditures.⁵

Other parts of the school budget typically cover facilities maintenance, as well as salaries for physical education (PE) teachers and, where made available, athletic trainers. But many sports programs lack full-time athletic directors to organize activities, and they often must cover budget gaps with football and basketball gate revenue, booster club support, and increasingly, pay-for-play fees or “optional” donations of several hundred dollars per season.

The fees pale in comparison to private club sport programs that have emerged over the past two decades. Many schools also offer fee waivers. Still, students from low-income families and communities of color often go unserved, for a variety of factors. On average, high schools populated predominantly by students of color have 25 roster spots for every 100 students; at heavily White schools, there are 58 spots per 100 students.⁶

POLICY

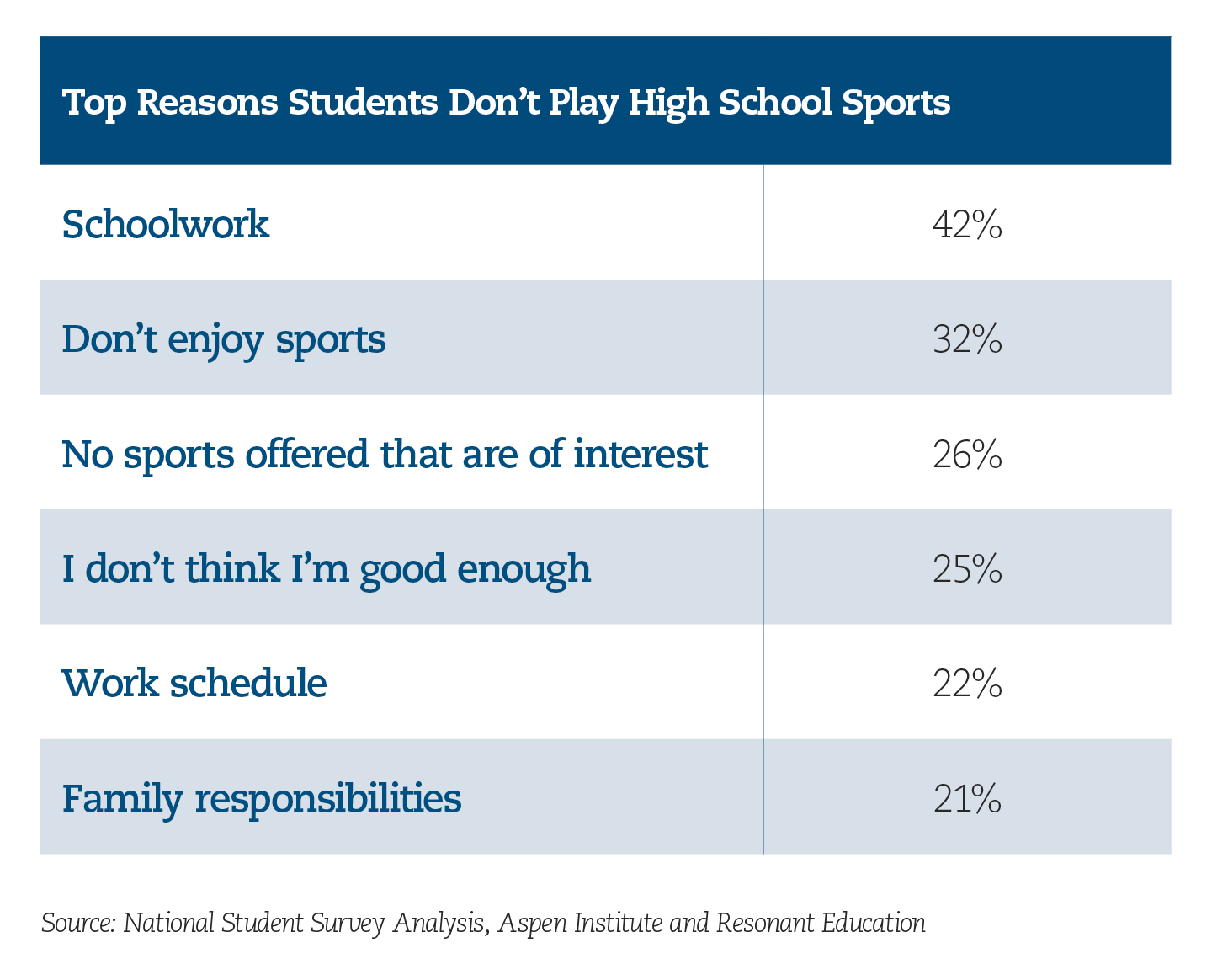

In the Aspen Institute’s national survey of nearly 6,000 high school students, the number one reason that students told us they don’t play sports is homework.⁷ More than 4 in 10 said academic demands leave them with no time. Participating on a high school team doesn’t help much with college applications unless you’re a recruited athlete. Neither do PE grades.

Today’s students live with the legacy of No Child Left Behind, the 2002 federal law that promoted testing in academic subjects at the expense of other programs. It was amended in 2015, identifying PE as part of a “well-rounded education” and offering new funds for PE programs.⁸ But many schools lack the capacity – or sufficient incentive – to seize the opportunity. While nearly all states have set standards for PE, most do not require a specific amount of instructional time and most allow exemptions, waivers or substitutions.⁹ Many school districts lack a staffer dedicated to overseeing PE. Some people just don’t feel compelled to support PE, assuming it was delivered the same way it was back when they were in school.

Without regular PE, students sample fewer sports and work less on their physical literacy.+

KNOWLEDGE

Superintendents, principals and school leaders are often unaware of innovations and alternate models that have found success elsewhere. They mostly work with what they are handed, a menu of interscholastic sports in which success is defined as winning championships, more than measures of student enjoyment and development. Membership organizations such as the National Federation of State High School Associations share promising ideas on their platforms but there’s a high churn rate of coaches and administrators, and universities increasingly focus on training sports business leaders instead of recreation professionals.

The absence of these assets threatens the historical bond that schools have with sports which goes back more than a century when the concept was introduced as a tool of nation-building. Between 2013-14 and 2017-18, public schools saw no growth in the participation rate of students despite an expanding economy, and the percentage of non-charter public high schools that offered sports decreased by 3%, according to an Aspen Institute-commissioned analysis of a U.S. Department of Education database.

Many schools with no sports programs have small student populations, making it challenging to field teams. Schools with fewer than five teams are three times more likely to eventually drop sports entirely than schools with five or more teams.¹⁰ Charter schools are growing, but often lack athletic facilities.

The COVID-19 pandemic very well could accelerate these trends, with students increasingly taking classes online or in small-group educational settings. Meanwhile, media opportunities have grown for schools with high-profile programs, creating more of a resource gap with other schools. So have opportunities for some high school athletes to market themselves through their name, image and likeness.¹¹ They face new pressures to specialize early in one sport.