Organized sports are starting to return for youth of all ages, though as of September, they are still half as active as they were prior to the pandemic. Parents are more willing to let their children play, and to spend money to support those activities, despite increasing concerns about the risks of COVID-19 transmission as well as transportation and scheduling concerns with school starting up again. Meanwhile, a growing number of youth have no interest in returning to the primary sport they played pre-pandemic – nearly 3 in 10 now.

Those are high-level takeaways from our latest national survey of parents. Below is a deeper dive on trends that are happening since the pandemic hit.

40%

Families whose child played their primary sport at least 4 days per week before COVID-19

A year ago, Project Play’s #DontRetireKid campaign grew public awareness of how common it is for kids to quit sports. No one could have envisioned that every child would be “retired” by March 2020. Prior to the COVID-19 shutdown, four out of 10 youth sports families saw their child play their primary sport at least four days per week, so the change was a jolt for many families.

By September 2020, when our latest survey was conducted, many parts of the country were back to playing sports. But some sports have returned more quickly than others, as have club teams in those sports, often traveling across county and state lines to find tournaments. Local recreational programs have struggled to get back to play.

Download the full Project Play COVID-19 Parenting Survey September 2020 report here.

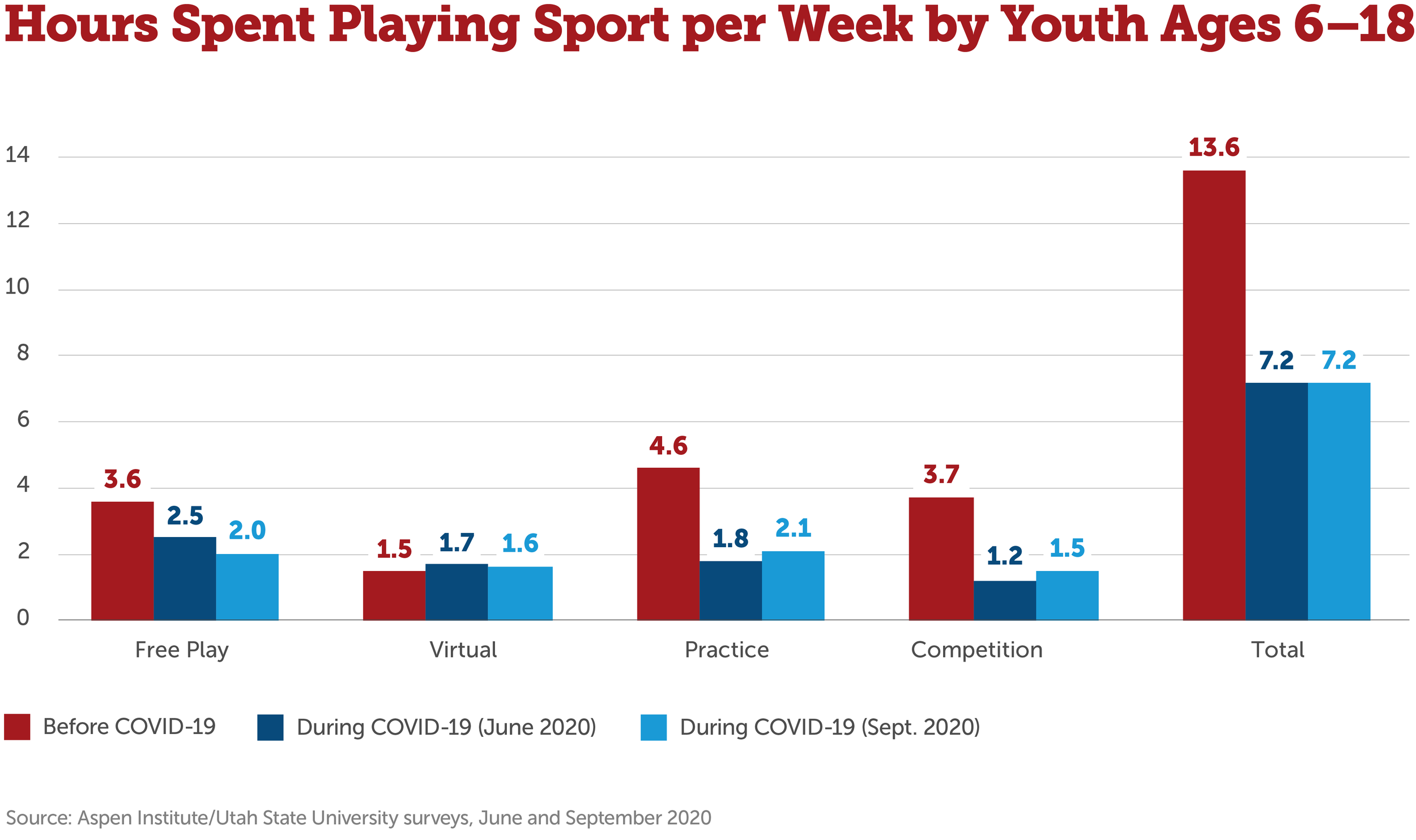

Overall, there has been less sport activity in all forms. The average child spends about 6.5 hours less per week on sports during COVID-19. Free play, practices and competitions have all significantly declined. Time spent on games have declined by 59% and practice hours are down 54% during the pandemic, though both saw increases in September 2020 compared to June 2020.

Gaps have grown, with sports becoming less accessible to lower-income youth. Children living in a household making $100,000 or more spend more than two hours additional time on sports each week during the pandemic than a child in a home under $50,000. That gap was less than one hour before COVID-19. While kids from all incomes have spent less time on sports now, having wealth seems to buffer a child’s loss of hours in free play, practices and games.

The pandemic accelerated trends toward at-home, virtual training. But the amount of time spent on such training has increased only 7% since the shutdown. Families making under $50,000 are seeing slighter increases in virtual training compared to wealthier families. Boys spent more time on virtual training before COVID-19; now girls are using it slightly more frequently than boys.

Prior to the pandemic, Black youth who played sports were the most engaged. Parents of Black youth reported that prior to COVID-19 their child spent more time playing sports (12.3 hours per week) than White children (11.6 hours). That’s flipped, with White youth (7.9 hours) now playing more than Black children (6.7 hours).

White youth returned to games faster. During COVID-19, White youth have spent 174% more time playing games than Asian youth, 46% more than Hispanic/Latino youth, and 39% more than Black youth. Before the pandemic, Black youth spent 13% more time on games than White youth, and the gap was not nearly as wide as it is now for Hispanic/Latino and Asian youth.

Children of all ages are playing sports less during the pandemic, but especially older youth. Parents of youth ages 15-18 reported a 65% reduction in time spent on practices or games, compared to 54% for 11- to 14-year-olds and 37% for 6- to 10-year-olds. Restrictions on middle and high school sports and travel sports likely explain the differences by age groups.

One of the most popular activities for youth was bicycling. While kids have significantly decreased their hours in most sports and activities during the pandemic, bicycling stayed about the same (9.1 hours per week during COVID-19, 10.5 hours per week before COVID-19). Bicycling went from the 16th-most popular activity pre-pandemic to No. 3 in hours spent during COVID-19, behind only tackle and flag football. “We’ve seen movement during the pandemic toward individual sports,” said Dr. Travis Dorsch, study director of the parent survey and founding director of the Families in Sport Lab at Utah State University.

Of the 21 sports/activities we tracked, parents reported increased hours by their child in 10 of them between June 2020 and September 2020. Some of the changes in time spent could be due to the sports calendar evolving to different seasons. Kids spent 29% more time on baseball in September than in June. Soccer moved slower with a 4% increase over those three months. Tackle football was up 10%. Basketball, a contact sport often played indoors during the winter, was down 10%.

Read "Youth volleyball coach: ‘Parents and players, please hold us accountable’ " here.

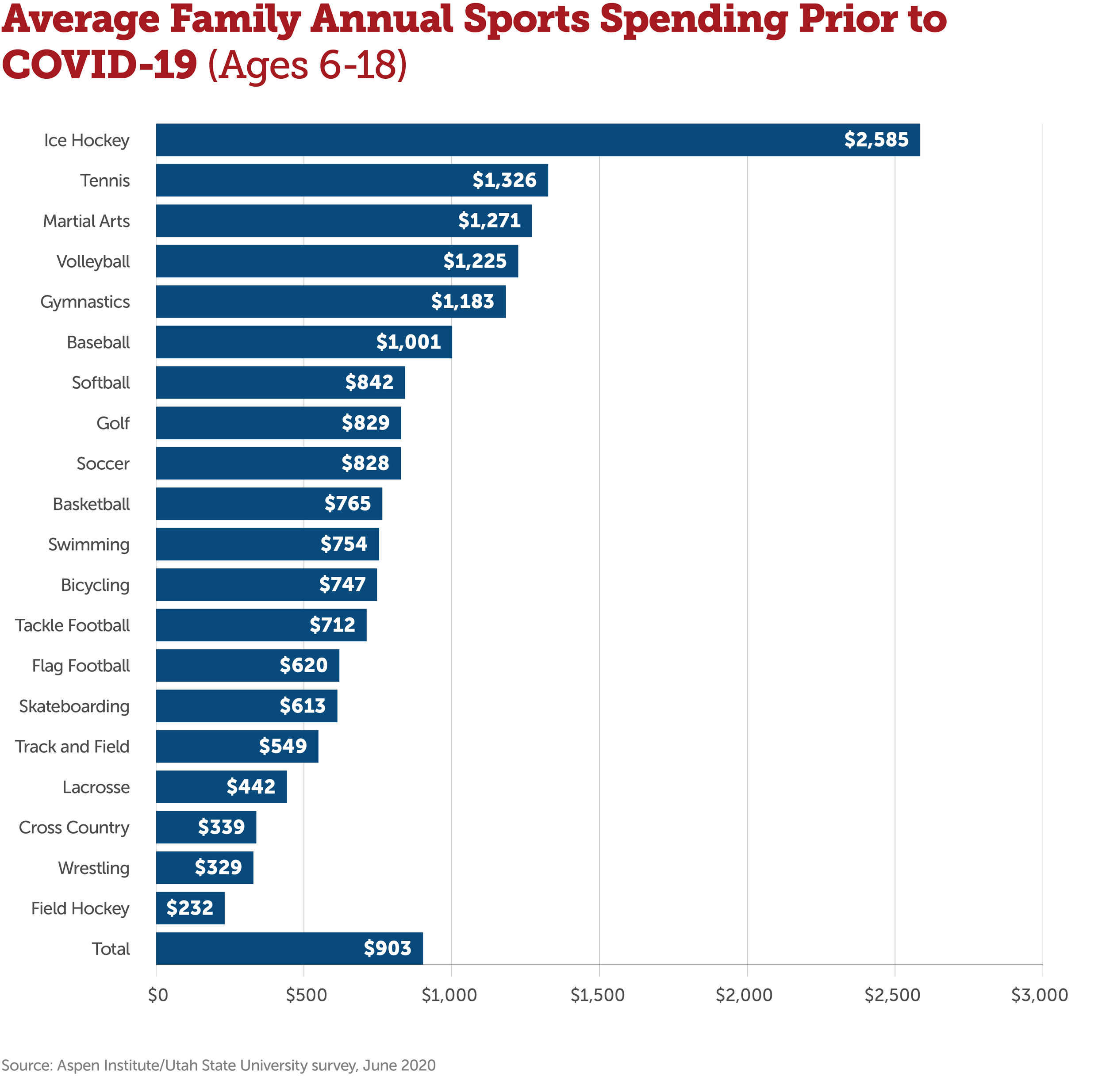

Prior to COVID-19 cancellations, the average family spent $903 per child annually across all sports. Parents with a child who considers hockey his or her primary sport spent almost twice as much money as the next closest sport (tennis). Parents living in the West ($1,445) spent about twice as much on youth sports as those in the Midwest ($740), plus more than families in the Southeast ($986), Northeast ($865) and Southwest ($849).

White parents reported spending more money ($894) than Black parents ($760). Spending by household income reflected just how commercialized the estimated $30 billion youth sports industry has become while leaving kids behind. Families making $100,000 or more spent $1,354 annually per child, compared to families between $50,000-$99,999 spending $908 per child, and families under $50,000 spending $561 per child.

29%

Parents who reported their child is not interested in sports

A very concerning number: 29% of parents reported their child is not interested in sports, up from 19% in June and 18% in May. Having three in 10 kids who previously played sports no longer interested should be a major red flag for the youth sports ecosystem.

“That’s a frightening number for the viability of the youth sports system, but also for the health outcomes coming down the pipeline for kids,” Dorsch said. “I think it’s really important that we acknowledge kids maybe don’t want to go back to sports the way they were. This is our opportunity to create a new youth sport system that kids want to come back to so we can reach that 29%, which is a moving target. How do we reframe the experience, whether it’s focusing on interpersonal coach-athlete features or health features or the competition itself? This looks like a real pivot point.”

64%

Parents who reported concern their child would get sick by resuming sports

Although some kids are returning to sports, the fear of illness increased for the third straight survey. In September, 64% of parents said they worried their child would get sick by resuming sports when restrictions are lifted, up from 61% in June and 50% in May. In theory, this runs counter to increased participation in sports and improving comfort level expressed by parents (see the next chart).

“Fear of illness and comfort in children’s sport participation may be mutually exclusive,” Dorsch said. “They might feel okay with their kids in sports because they’re outdoors, because leagues have taken precautions, because they haven’t seen evidence of outbreaks while simultaneously acknowledging that they or their kids might get sick at school, church, grocery stores or any in any other context.”

Asian (77%), Hispanic/Latino (73%) and Black (68%) parents expressed this fear at higher rates than White parents (60%). Black and Hispanic/Latino people are twice as likely to test positive for COVID-19 as White people, according to a study by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Black people tested at a rate of 60 per 1,000 people, compared to 52.7 per 1,000 among Hispanic/Latino people and 38.6 per 1,000 among White people.

Youth sports parents in our survey also reported increasing potential barriers to resume sports due to schedule conflicts and transportation. As children return to school and parents get back to work, juggling schedules and how to get kids to games and practices are returning as challenges.

Read "Business vs. safety: USSSA guidelines for travel sports raise concerns" here.

Families across all races reported being more willing in September than they were in June to spend more money on youth sports when COVID-19-related restrictions are lifted. In September, 28% of parents said they would spend more on sports when they return, up from 21% in June. Still, more than one-quarter of parents said they expect to spend substantially or a little less.

28%

Parents who reported they would spend more money on sports when they return

“They’re more likely to spend more money, but they’re more concerned about health outputs,” Dorsch said. “It could be that, yes, parents are afraid of getting sick, but we all have cabin fever and we’re trying to weigh the positives and negatives of getting back into sports.”

From June to September, parents of all races became more comfortable with children’s participation in all forms of sports. In most cases, White parents are more comfortable than parents of other racial backgrounds.

Among all parents, individual pickup games remain the form of sport with the highest comfort level (71%). Travel sports (52%) is gradually becoming more comfortable to parents, though it still trails community-based sports (58%) and interscholastic sports (57%). “Parents are in a tough position,” Dorsch said. “They’re weighing a lot by trying to keep their families safe and trying to give their kids experiences. Kids don’t want to lose this competitive time period. To lose six months of sport is an eternity for a young person. It’s a hard balance for parents.”

Concerns are also growing that local programmers that traditionally have engaged youth at scale (parks and recreation departments, YMCAs, Boys and Girls Clubs, Police Athletic Leagues, etc.) won’t be able to keep up with intense, organized team sports that have private resources and are further ahead in the recovery process.

Sports & Fitness Industry Association CEO Tom Cove said trends show that club and travel sports teams are returning much faster than local rec leagues. “Many surveys say parents aren’t sending kids back, and then the first travel tournament returned after three months, and the return was not gradual at all,” Cove said. “If you get communication from your team that you’ve been involved with for four years and the coach says, ‘We’ll organize this way with this protocol,’ what appears to be happening is the parent of a kid on the travel team says, ‘I trust that coach, he’s serious, I’ll let my kid go.’”

Middle school and high school sports have been in a state of confusion. Depending on the community, sports are opening or closing – or sometimes both. Some students are even transferring across state lines in order to play in high school this fall. As of September 2020, more states were gradually reopening high school sports, including some states that opened against the advice of public health departments, but at a slower rate than other forms of sports.

Of the parents who suggested their children participated mostly in interscholastic sports before COVID-19, only 37% said school sports opportunities are available at the same level as before. That’s less than what parents reported about available opportunities for community-based sports (51%), intramurals (49%), and travel/elite/club (40%).

Four of 10 parents reported in September that their child has not participated in new recreational activities during the pandemic, down from 51% in June. Of the parents whose children tried a new sport or recreational activity, 37% tried two or more. But only 46% of those parents believe their child would continue with that activity once organized youth sports return (down from 60% in June).

Parents reported 68% of free play opportunities are now available. There’s been new enthusiasm for pickup play and other forms of unstructured sports activity. In June, sales were up 203% year over year for inexpensive leisure bikes and up 150% for mountain bikes. They represented the styles that most contributed to overall bike sales growing 63% in June compared to 2019.

A study by the University of Wisconsin found that 65% of adolescent athletes reported anxiety symptoms in May, with 25% suffering moderate or severe anxiety. Physical activity was down 50% during the pandemic, according to the study, which surveyed approximately 13,000 athletes nationally and did not compare the data to the general student population. The 50% decrease in activity was “much more than what we thought it would be,” said Tim McGuine, the study’s author. “We see physical activity go down in kids post-injury and this is lower.” Read the full study here.

High school-age athletes reported more symptoms of anxiety and depression the older they are, with moderate to severe anxiety peaking in the 12th grade for both females (38%) and males (35%). Senior year can provide a lot of anxiety for all students during the pandemic given the uncertainty over present and future academic and athletic plans. Team-sport athletes who come from high-poverty homes reported higher levels of anxiety (44%) and depression (28%) than those who live in wealthier households.

The mental health challenges reported by athletes “illustrate to a great extent the value that schools are providing,” McGuine said. “We’ve come to realize that school is not just school. When kids can get their academic work done online in two or three hours, what are they doing the rest of the day? At school, they’re immersed in peer support and other ways that schools expand social and psychological benefits, not just academic. Schools challenge kids on how to work together as a team.”

McGuine also questions how much some athletes will practice proper COVID-19 protocols without a team structure requiring it in order to play. “For all we want to blame peer pressure on bad decisions kids may make, there’s also a body of evidence that positive peer pressure is important to keep kids in a structured environment,” he said. “If we don’t have sports as a carrot for kids, are they as likely to socially distance and wear a mask?”

Read "Player advice for coaches on mental health: “Don’t talk at me, talk to me”" here.

As Project Play focuses stakeholders on the need to develop more community-based play, let’s remember why most parents want their child to play. It’s not for competition, as often discussed publicly. The most important outcomes for parents: mental health, physical health, fun, social skills and peer relationships.

“Parents appear to really be valuing right now the physical, emotional and social benefits of sport,” Dorsch said. “Without in-person school in some places, sport becomes a vehicle where kids can still hopefully get these benefits. I also think a lot of parents view healthy competition as an important part of sports, and through competition, you can gain all of these other benefits. I think sometimes we create a false dichotomy over desired outcomes. They’re not mutually exclusive.”

Data on this page primarily came from three online surveys of youth sports parents conducted by the Aspen Institute, Utah State University and North Carolina State University to understand attitudes and behaviors before and during COVID-19. Surveys were conducted in 2020 during the months of May (1,050 responses), June (2,603 responses) and September (1,103 responses). The surveys were a statistically representative subset of youth sports parents in the United States. Participant quotas were established based on sociodemographic grouping variables recently published by the U.S. Census Bureau as well as past research on families with one or more children actively participating in organized sports. Surveyed participants had children between the ages of 6 and 18 who play sports and represented all 50 states and Washington D.C.