Among children who play sports, those with disabilities annually participate almost one month less in practices or competitions than their peers without disabilities. The lack of play can be impactful – parents of children with disabilities are more likely to believe their child’s health worsened when not regularly playing sports.

Project Play survey: Parents spend 3+ hours every day on child’s sports

If you’re the parent of a child in sports, chances are your life gets extremely hectic. It’s not just the extra costs with sports, although a 46% increase on family spending since 2019 that surpassed U.S. inflation leaves parents frustrated. It’s also their time commitment.

Project Play survey: Youth lose one week of sports a year due to climate extremes

Youth sports parents nationally estimated their children lost about a week of sports practices or competitions in 2024 due to very hot temperatures, wildfires or wildfire smoke, flooding or changing winters. The new research by the Aspen Institute, Utah State University and Louisiana Tech is a rare estimate of how frequently our changing climate impacts sports activities for children in the U.S. – and a likely precursor of future challenges to safely play sports.

Project Play survey: 11% of sports parents believe their child can go pro

Project Play survey: Parents justify sport specialization so their child can play in high school

Project Play survey: Family spending on youth sports rises 46% over five years

Participation in youth sports is getting more expensive – and there seems no end in sight.

The average U.S. sports family spent $1,016 on their child’s primary sport in 2024, a 46% increase since 2019, according to the Aspen Institute’s latest parent survey in partnership with Utah State University and Louisiana Tech University. The rising commercialization of youth sports impacts who can access quality sports opportunities or whether some children play at all.

Analysis: Serious knee injury among teen athletes grows 26%

Among the most dreaded injuries in sports, the rate of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries among high school athletes has grown significantly over the past 15 years, according to a new data analysis by organizations collaborating to assess and address the problem of serious knee injuries.

The National ACL Injury Coalition reviewed injury data for 12 major girls and boys sports over five three-year periods from 2007 to 2022, as supplied by certified athletic trainers in the High School RIO surveillance program. From period one to five, the average annual ACL injury rate grew 25.9% to 7.3 injuries per 100,000 athlete exposures. ACL injuries now represent more than 14% of all injuries involving the knee.

Projected benefits if U.S. lifts youth sports participation to 2030 goal: $57B

Survey: High school students want more sport, physical activity options

Wealthier children are playing sports more during COVID-19

Survey: High school students worry about COVID-19, still want to play sports

Survey: Parents grow more worried about their child returning to sports

TeamSnap data: Youth sports teams return to play faster than expected

Survey: 50% of parents fear kids will get sick by returning to sports

Survey: Sports parents now spend more money on girls than boys

Survey: African-American youth more often play sports to chase college, pro dreams

This article shares new insights on the sports experience for youth across racial subgroups, based on a national survey of sports parents by the Aspen Institute’s Project Play initiative and Utah State University’s Families in Sport Lab. The data show sharp differences in access, and in pressures experienced by young athletes.

Survey: Low-income kids are 6 times more likely to quit sports due to costs

In this post, we break down the data by family income. Youth sports have become an estimated $17 billion industry, often leaving behind families who cannot afford to keep up with the escalating arms race. In our latest analysis of the parent survey, we explored participation rates, free play, pressure on kids, and costs to play by evaluating responses against household income.

Staying in the game: Progress and challenges in youth sports

In the often confusing and frustrating world of youth sports, some progress is being made. The Aspen Institute Sports & Society Program’s Project Play discovered these trends within research of kids ages 6 to 12:

The percentage of kids playing team sports on a regular basis increased for the third consecutive year. Baseball, cheerleading, gymnastics, lacrosse, softball, swimming, tennis, volleyball and wrestling all registered positive bumps.

Fewer kids were physically inactive for the fourth consecutive year.

Multisport play continued to make a slight comeback.

Those are among the key findings from the Aspen Institute’s State of Play 2019 report released today on how well stakeholders served children through sports over the past year. To that end, the Project Play 2020 campaign, “Don’t Retire, Kid” campaign, raises awareness about gaps in the youth sports system that cause kids to quit sports or not start in the first place – and solutions to keep them in the game.

But major gaps remain. While regular sports participation increased to 38% in 2018, it’s still far from the level of 45% in 2008. Kids from lower-income homes are more than three times as likely to be physically inactive. Families are spending on average almost $700 per child for one sport each year, with some parents spending tens of thousands of dollars. And less than three of 10 youth coaches have been trained within the past year.

Below is Project Play’s annual release of charts showing the national landscape in youth sports compared to past years. Unless otherwise noted, all data were provided to the Aspen Institute by the Sports & Fitness Industry Association (SFIA), which in 2018 commissioned an online survey of 20,069 individuals through Sports Marketing Surveys.

On average, a family annually spends $693 per child in one sport, according to a 2019 national survey of youth-sports parents by the Aspen Institute and Utah State University Families in Sport Lab. The most expensive sports: ice hockey ($2,583), skiing/snowboarding ($2,249), field hockey ($2,125), gymnastics ($1,580), and lacrosse ($1,289). The latest expensive: track and field ($191), flag football ($268), skateboarding ($380), cross country ($421), and basketball ($427).

The average child today spends less than three years playing a sport and quits by age 11, most often because the sport just isn’t fun anymore, according to the Aspen Institute/Utah State parent survey. The sports with the longest shelf life: field hockey, skiing/snowboarding, and flag football.

More than four in 10 coaches reported having never received training in concussion management, general safety and injury prevention, physical conditioning, and effective motivational techniques. The latest numbers also make clear that when coaches do get trained, it’s typically not on an annual basis.

Given how difficult it is to find volunteer coaches, the 2018 numbers continue to show how more coaches can be added. Only 27% of youth coaches were female, up from 23% in 2017 but still very low. There are also very few coaches of high school and college age, and not many senior citizens who coach.

Good news: The percentage of kids who play at least one day during the year has held steady for five straight years since increasing in 2014. Also, the amount of kids playing team sports on a regular basis increased in 2018 by nearly a full percentage point. The bad news: For the third straight year, fewer kids are playing an individual sport.

Kids played an average of 1.87 team sports. It’s the second straight year with a slight improvement, though still well below the level of 2011 (2.11). Anecdotally, there are signs that kids are sampling more sports but still playing one sport year-round against the advice of medical experts due to the risk of burnout and overuse injuries.

This statistic showed a rare increase in 2018. Important note: SFIA changed this definition in the past year, though percentages for previous years have also been adjusted based on the new definition.

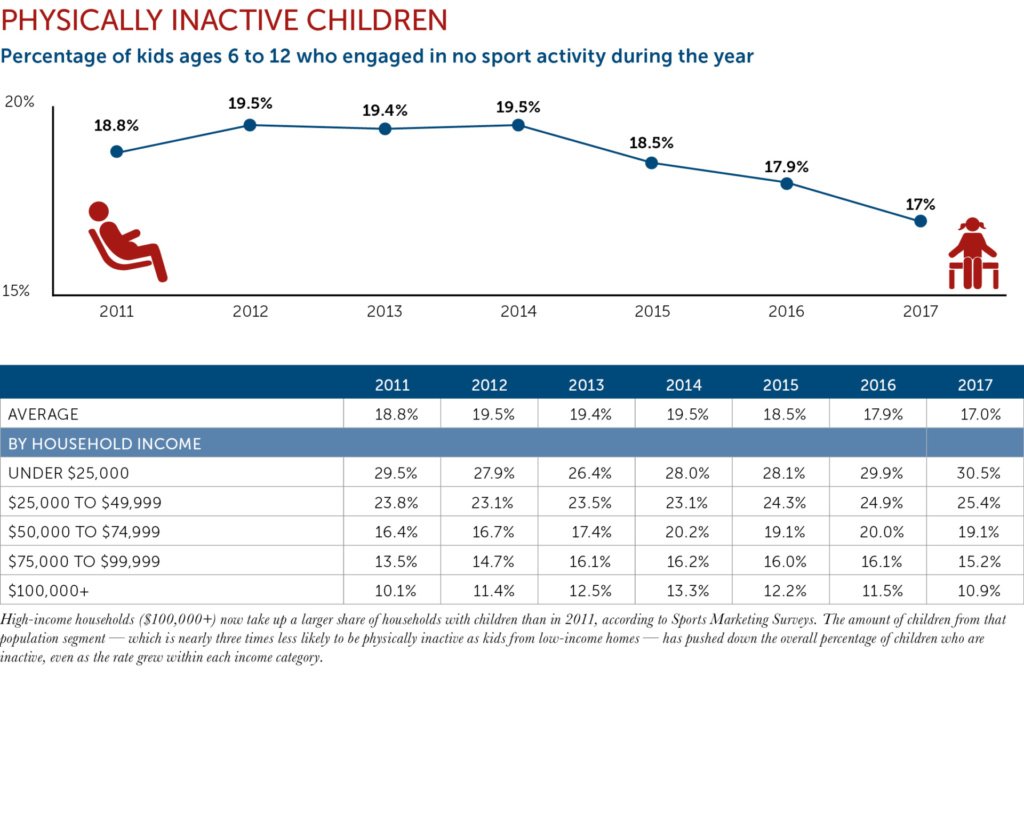

Each year, this continues to be the most positive statistic we track. The percentage of physically inactive children has now decreased for four consecutive years, from 19.7% in 2014 to 17.1% in 2018. That’s still too many children not moving their bodies, but it’s a major advance. Every household income category had fewer inactive children except one: Kids in homes under $25,000, where the inactive rate has gone from 24.4% in 2012 to 33.4% in 2018.

The gap between girls and boys regular participation sports has closed since 2012. But that’s because the percentage of boys dropped significantly in those six years, compared to a modest decline by girls. Kids who identify as Asian/Pacific Islander were the only ethnicity to increase regular sports participation.

Read State of Play 2019 to learn all 40 developments regarding the latest youth sports trends over the past year. The report is sponsored by Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS).

Story was originally published here.

Survey: Kids quit most sports by age 11

The average child today spends less than three years playing a sport, quitting by age 11, most often because the sport just isn’t fun anymore. Their parents are under pressure, too, with some sports costing thousands of dollars a year and travel expenses taking up the largest chunk.

These are among the findings of a new national survey of parents of youth athletes conducted by the Aspen Institute with the Utah State University Families in Sports Lab. The results offer key insights on the contemporary challenges of getting and keeping kids involved in sports, the theme of a new public awareness campaign, “Don’t Retire, Kid”, that launches Aug. 4.

10 charts that show progress, challenges to fix youth sports

Flag football surpassed tackle as the most commonly played form of the game for kids ages 6 to 12 in 2017. Fewer kids are physically inactive. Sampling of most major team sports is up. Most coaches are still winging it. And kids from lower-income homes face increasing barriers to sports participation.

Those are among the key findings from the Aspen Institute Sports & Society Program’s State of Play: 2018 report released on October 16 at the Project Play Summit. Progress is being made in some areas; much more improvement is needed to realize the goal of every child having access to quality sports, regardless of zip code or ability.

Below is Project Play’s annual release of charts showing the national landscape in youth sports compared to past years. All data are for kids ages 6 to 12 and were provided to the Aspen Institute by the Sports & Fitness Industry Association, which in 2017 commissioned a survey of 30,999 individuals through Sports Marketing Surveys.

The biggest news: Flag football (3.3 percent) surpassed tackle football (2.9 percent) for kids ages 6 to 12 who played sports on a regular basis. The sports with the largest three-year participation increase were flag football (38.9 percent) and competitive cheerleading (29.8 percent). Tackle football was down almost 2 percent.

Ten of the 15 sports tracked by Project Play saw increased participation on a regular basis in 2017. That’s progress, though the big three sports for kids (soccer, baseball, and basketball) are still down significantly from a decade ago. In 2017, only bicycling, tackle football, soccer, swimming, and tennis experienced one-year declines.

Churn rate means the difference between the number of kids a sport loses compared to the number who return or try the sport for the first time. In 2017, among the nine sports evaluated by Project Play, cheerleading, baseball, and flag football fared the best in retaining and bringing in new participants. Baseball lost the fewest percentage of kids (18.4 percent). Soccer was at the bottom of the list with a negative 7.7 percent net churn rate.

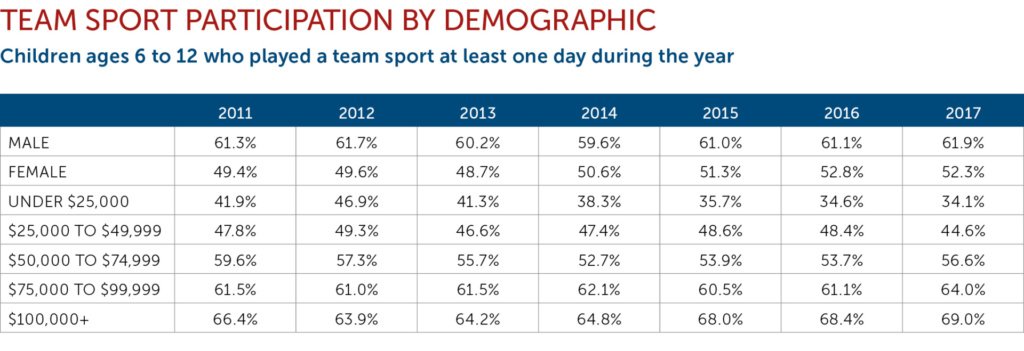

Consider this: In 2012, 46.9 percent of kids ages 6-12 in household incomes of under $25,000 played a team sport at least one day. At the time, there was very little difference in participation numbers between those children and kids in homes with incomes of $25,000 to $49,000 (49.3 percent). And even the gap between the lowest- and highest-income kids was “only” 17 percentage points. By 2017, that gap had doubled to 34.9 percentage points. The kids in homes under $25,000 were now 10.5 percentage points behind just the next highest class. Poorer kids are being left behind in all aspects of society, and sports is no different.

Less than four in 10 youth coaches say they are trained in any of the following areas: sport skills and tactics, effective motivational technique, or safety needs (CPR/basic first aid and concussion management). Lacrosse had the highest percentage of trained coaches in four of the six competencies; soccer was last in five categories. For the third straight year, soccer ranked last among coaches trained in concussion management (25 percent). Lacrosse was the highest (48 percent). Lacrosse, flag football, and volleyball coaches were the most trained in general safety.

Women remained an untapped area to develop more youth coaches. In 2017, only 23 percent of adults who coached kids 14 and under in the past five years were female. That was down from 28 percent in 2016 and the lowest on record dating to 2012.

Younger and older citizens also could be recruited as coaches. In 2017, 81 percent of youth coaches were between the ages of 25 and 54. Some of that is natural since that’s the period when people tend to have children playing sports. But high school and college students and retired citizens are available to help too.

The percentage of children who played a team sport at least one day in 2017 slightly increased for the third straight year. But the percentage of kids who played team sports on a regular basis in 2017 (37 percent) remained a far cry from 2011 (41.5 percent).

Children in our age group played an average of 1.85 team sports in 2017 – the first improvement in four years, albeit a slight increase. As recently as 2011, kids were averaging more than two sports (2.11). Still, 2017 marked progress.

This statistic perennially shows a decline. In 2017, only 23.9 percent of kids in our age group regularly participated in high-calorie-burning sports. The figure was as high as 28.7 percent in 2011.

Good news: The percentage of physically inactive children has now fallen for three consecutive years, from 19.5 percent in 2014 to 17 percent in 2017. That’s still too many children not moving, but it’s a major advance. In total, roughly 700,000 more kids are now off the couch and doing something.

Read the entire State of Play: 2018 report here. Watch videos and read companion content from the 2018 Project Play Summit. Project Play released new tools, reports and commitments to help more kids get active through sports.

Story was originally published here.