Photo: Getty Images

The Aspen Institute’s Project Play initiative partnered with Utah State University and Louisiana Tech University to survey youth sports parents, releasing in March a 148-page report that helped inform several sessions at 2025 Project Play Summit. Now, we’re analyzing key findings in depth. This fourth story in our year-long series examines the impact of climate change on youth sports.

Mitchell Huggins was one of those community heroes who makes youth sports work, a beloved umpire known as “Mr. Mitch” to the softball players whose games he called in Sumter, South Carolina. On June 21, he was behind the plate again in all his protective gear, as temperatures soared to 91 degrees.

This time, it was just too much. Tragically, Huggins, 61, passed out during a game and died of heat stroke. Parents told a local TV station they were concerned about why the tournament was allowed to continue in such extreme weather conditions.

The death of Huggins is sadly too common. Each summer, preventable heat-related deaths happen in youth and high school sports. Football is by far the most dangerous sport. Since 1996, 72 football players have died from exertional heat stroke (52 high school, 15 college, two professional, two organized youth, and one middle school), according to the National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research.

And as the climate continues to warm, competitions and practices are sometimes adjusted in hopes of preventing more tragedies.

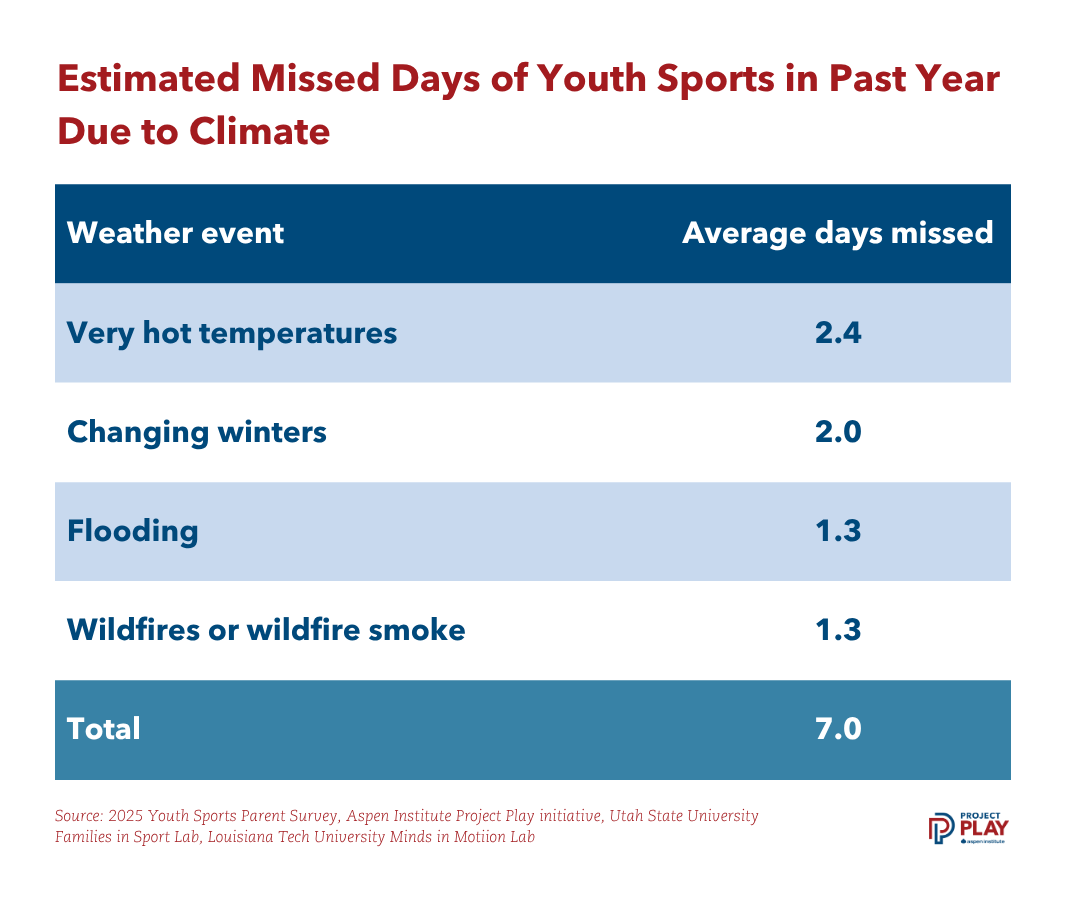

Youth sports parents nationally estimated their children lost about a week of sports practices or competitions in 2024 due to very hot temperatures, wildfires or wildfire smoke, flooding or changing winters. The new research by the Aspen Institute, Utah State University and Louisiana Tech is a rare estimate of how frequently our changing climate impacts sports activities for children in the U.S. – and a likely precursor of future challenges to safely play sports.

Black parents, who are more likely to live in geographic areas that are vulnerable to weather disasters, reported twice the number of sports cancellations than White and Hispanic parents. And in California, where wildfires are often prevalent, parents estimated their child lost 13 days due to extreme weather, almost twice as much as the national average.

How, or if, children safely play sports and recreate outdoors continues to be impacted by climate change. And the challenges are not going away.

Most U.S. cities now experience at least one additional week’s worth of extremely hot days than in the early 1970s, according to research by Climate Central. Eighteen cities – mostly in the South and Southeast – now have at least 30 additional extremely hot days each year than in 1970, led by Miami (50 more extremely hot days).

In Japan, researchers describe a looming crisis for children’s health, as Japan’s intense summer heat merges with a deeply ingrained sporting culture, creating conditions that could pose serious health risks. By 2060, summer temperatures in Japan could become so dangerously high that outdoor sports for children may need to be suspended entirely during parts of July and August, warned a study by Japan’s National Institute for Environment Studies.

In the Upper Midwest of the U.S., warm temperatures and low snowfall are causing significant difficulties for youth cross-country skiers during winter, according to University of Minnesota research. Due to these conditions, coaches perceive negative changes in their athletes’ fitness levels and motivation and their teams’ schedules and finances. Although coaches are trying to find creative solutions, they worry they will have more difficulty recruiting new athletes, making the sport even more inaccessible for less-resourced teams.

And in the Southeast, many communities that suffer hurricane and flooding disasters never recover to resume providing sports opportunities for children, said Jessica Murfree, an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina who studies sports and climate change.

“They don’t have balls, nets, fields and other needs because weather continually impacts their community,” she said. “There’s a huge gap between the capacities of elite youth sports and parks and rec community centers. In climate research, we call it organizational climate capacity – your capacity to return to play. The gap widens, meaning for the organizations that can return to play, it becomes easier for them, and for the ones facing more challenges, it becomes harder.”

Meanwhile, the sports facilities industry is “not prepared at all, plain and simple” for the changing climate, Maryland SoccerPlex Executive Director Matt Libber said at a 2025 Project Play Summit session on the subject. “We’re not putting climate change in the equation when we’re building these facilities. It’s who can build it faster, bigger, better, and it’s going to come back and bite us at some point.”

Libber is adjusting. His soccer complex in Maryland faced a drought in summer 2024 that increased its water bill to $50,000. The complex has since transitioned to Bermuda grass that requires less water, built drains on every field to eliminate most rainouts, and added solar panels on its roof that cut the electric bill in half.

Staff are more conscious of field temperatures. Athletic trainers carry a cheat sheet to decide if there should be activities in extreme heat or cold.

“One problem is a lot of this work is super expensive,” Libber said. “The other problem is, and we learned this through the pandemic, no one wants to be the first to (make changes due to climate) in a highly politicized conversation. The facilities that shut down for COVID early had a lot of backlash and the ones that stayed open forever had a lot of backlash.”

The Aspen Institute survey also asked youth sports parents whether they would be amenable to sports providers changing their child’s sport season to another time of year if weather and disaster events continue to impact scheduling. About half of the parents said yes.

More than half of urban parents were open to changing sports seasons (54%), higher than suburban (44%) and rural (41%) parents. That’s not surprising since cities, with extensive use of pavement, buildings and other heat-absorbing materials, tend to be warmer than surrounding rural areas. Urban areas also have less natural cooling mechanisms like trees, vegetation and water bodies.

Black (54%) and Hispanic (53%) parents were amenable to changing sports schedules at a higher rate than White parents (46%). The Brookings Institute reported that Black adults are more concerned about climate change than the national average. Black Americans are 40% more likely to live in areas with the highest projected increases in mortality rates due to climate-driven changes in extreme temperatures, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

In Aspen’s survey, basketball and soccer parents were slightly more open to schedule changes than baseball parents.

Libber cautioned that the feasibility of moving entire youth seasons would be challenging because of shared facility use, particularly with football, soccer and lacrosse. There would be cultural challenges in some communities too. For instance, in the deep South, life revolves around football season in the fall – a tough habit for some to break.

But major pro sports events such as the World Cup have rescheduled championships due to climate, and that will need to happen among youth for sports to survive the climate crisis, Murfree said.

Because climate change impacts areas of the U.S. differently, Murfree said making a national youth sports policy on this subject would be very difficult. Policies addressing heat illness and heat acclimatization in sports are sometimes set by state high school athletic associations or by state or local governments. Often, these policies only apply to school sports, not community-based leagues, travel teams or other recreational activities.

“Some states refer to national guidelines, and sometimes it’s a moving goalpost and they defer to each other,” Murfree said. “Finding who implements and enforces the policy is more important than finding the policy itself. If you’re a teacher, parent or coach, you need to know who’s in charge of adhering to the policies to ensure children are kept safe.”

How sports get offered to children may need to adjust too – even something as common as a child playing up on a team with older age groups. Murfree believes that may need to change in some circumstances.

“We teach kids in growing bodies who might not be able to advocate for themselves that they need to toughen up or play up an age group, and that might not be in the best interests of their health because the environment is changing,” she said. “There’s a massive difference in the risk of adverse health outcomes based on the amount of exertion a child has in sunlight, and your body has to work harder if you’re in an older age group. Let’s have water breaks, timeouts and be able to advocate for yourself to sit in shade.”

How some coaches communicate with players will need to evolve. Libber believes coaches need climate training, not unlike how concussion training became so prominent in the last decade or so as head injuries gained more attention. Coaches could be trained in how to address heat concerns, parameters for mandatory water breaks, and returning to what Libber calls “compassionate leadership” in youth sports.

“Youth sports should be about playing outside, having fun, and learning how to communicate, but it’s not that anymore,” Libber said. “It’s about how much money do parents have to pump into this? If that remains the focus, we can forget about smart, responsible leadership from adults who are supposed to protect kids with decisions in their best interest.”

Murfree and Libber are both confident that sports can continue to be played safely outdoors – as long as adults become more flexible.

“It’s going to take a lot of work and a lot of buy-in, but there is proof of concept of (adapting),” Murfree said. “The pandemic really showed us that when things are catastrophic, scary and changing, we want to have sports so badly that we’ll do what it takes to adjust.

“Just like the pandemic, we’re experiencing a massive, disruptive event to sport and to life in general with the climate crisis. If sport continues into the future, we’ll need to see some of those changes. It might be as small as shifting a week or so (of the event) or even time of day as opposed to the entirety of the season. But starting to get comfortable with that discomfort is really important.”

Jon Solomon is Community Impact Director of the Aspen Institute Sports & Society Program. Email him at jon.solomon@aspeninstitute.org.

Survey Methodology

The Aspen Institute’s National Youth Sports Parent Survey, in partnership with Utah State University and Louisiana Tech University, utilized a nationally representative survey of 1,848 youth sports parents whose children participate regularly in one or more sports activities. The survey was conducted online in November and December 2024 with parents of children ages 6-18 from every state and the District of Columbia. The research sought to address patterns of youth sports participation, parents’ involvement in that participation, and the characteristics of the settings in which participation occurs. Read the full survey results. The Aspen Institute will publish additional analysis of the results throughout 2025.