Photo: Getty Images

The Aspen Institute’s Project Play initiative partnered with Utah State University and Louisiana Tech University to survey youth sports parents, releasing in March a 148-page report that helped inform several sessions at Project Play Summit 2025. Now, we’re analyzing key findings in depth. This third story in our year-long series examines parent goals and expectations for their child’s sports career.

Roughly two in 10 youth sports parents believe their child has the ability to eventually play Division I college sports, and one in 10 think their child could reach the pros or Olympics.

Last month, the Aspen Institute reported that the biggest driver promoting early sport specialization is children simply making the high school team. While that is true for the majority of parents, there remains a faction who believe their children will beat the long odds and play sports at the highest levels, according to the Aspen Institute’s parent survey in partnership with Utah State University and Louisiana Tech University.

NCAA statistics show that only a minuscule percentage of high school athletes will play professional sports.

1 in 610 (0.16%) will get drafted by a Major League Baseball team

1 in 10,399 (0.0096%) will get picked by an NBA team

1 in 12,873 (0.0077%) will be chosen by a WNBA team

1 in 3,960 (0.025%) will get picked by an NFL team

Because some parent expectations are so high, “they are extremely financially and emotionally invested in their kids’ sports,” iSport360 founder Ian Goldberg said at a 2025 Project Play Summit session on the parent survey results. “They’re literally delusional.”

While this is surely true for some parents, there is also nuance to parents’ expectations.

“I thought my daughter could play professionally or in the Olympics as a water polo player. I believe that,” said Asia Mape, founder of the “I Love to Watch You Play” website and a speaker at the Project Play Summit. “I also think it’s important to remember that it’s OK. Dreaming is a big part of what we’re doing for our kids. … That’s sort of our role. We support, we guide, we grow.

“But then there comes a point where we have to pivot, and this is one of the biggest problems. We don’t pivot with our kids. We stay stuck on their initial dreams. We stay stuck on our dreams for them. And when they change, we have to change. Or when society tells us we have to change because they’re not making their high school or middle school team, then we have to pivot with them.”

In the Aspen Institute survey, parents of Black children reported the strongest belief that their child can eventually reach the highest levels of sports. They were two times more likely to think their child can play professionally than White and Hispanic/Latino parents.

Tackle football parents had the highest belief their child can play high school, Division I and professionally. Parents of boys and girls had nearly identical sports aspirations for their child.

“For a small subset of kids, they go on to be elite athletes and that can be really terrific for them and their future prospects,” University of Baltimore law professor Dionne Koller said in a recent interview promoting her new book More Than Play: How Law, Policy, and Politics Shape American Youth Sport. “But for the millions of kids who get involved, continuing to professionalize youth sports by emphasizing year-round training and skill-building can be a little too much for their minds and bodies.”

For some families, simply accessing expensive sports leagues is a barrier. While parents of all income levels believed at relatively equal levels their child can play rec and high school sports, there were gaps by wealth in believing their child has the ability to play travel sports.

“These data reinforce the true value of sport: that when children engage in appropriately designed settings, they experience better quality of life across a number of personal domains,” said Travis Dorsch, co-author of the Aspen Institute parent study and founder of the Families in Sport Lab at Utah State University. “That is the promise we should be focused on keeping.”

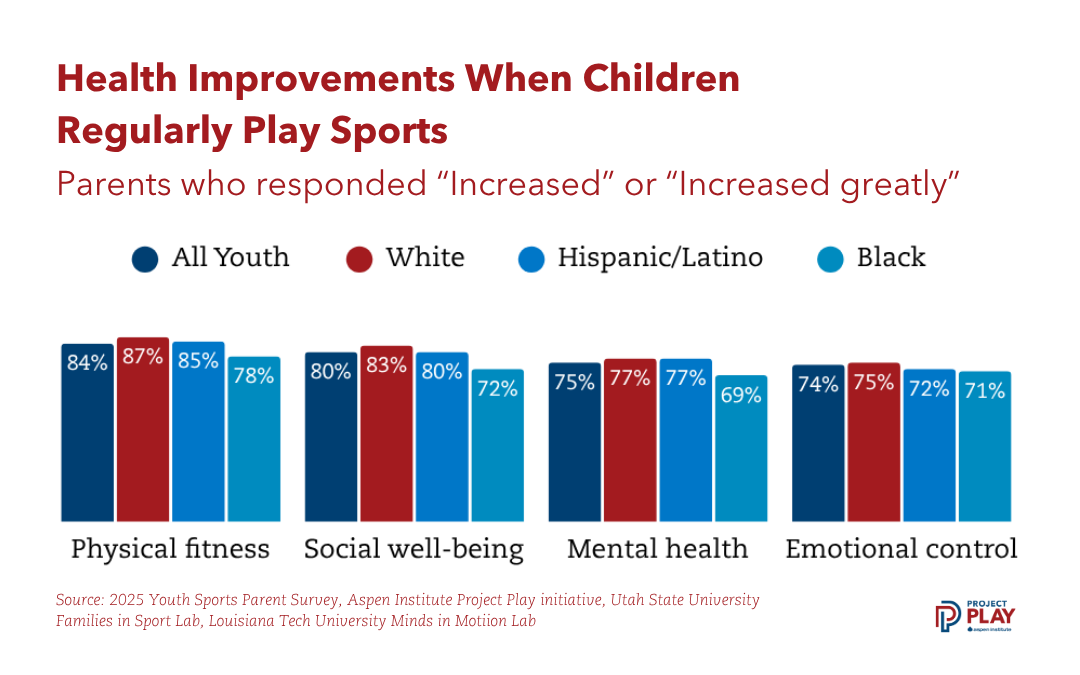

On-field success is not the only endgame parents hope their children achieve through sports, even among those who believe their child can thrive athletically. In the Aspen survey, roughly three-quarters of sports parents said their child’s mental health, physical fitness, emotional control, and social well-being improves when they regularly play sports.

Nearly eight in 10 urban parents (79%) reported their child’s emotional control typically increases when regularly playing sports, higher than rural (72%) and suburban (69%) parents. Parents of older children reported at higher rates that their child’s mental health improves when they are regularly engaged in sports.

Other research also shows nuance about what parents want from sports. A 2024 study of the San Francisco Giants’ youth baseball program found that the Junior Giants’ focus on youth-development goals, such as building character, can increase the likelihood of children returning to the program. The Junior Giants is a free program for children ages 5-18 and doesn’t keep score of games or create standings.

For every unit increase in positive changes to their child’s confidence, integrity, leadership and teamwork, parents were 2.38 times more likely to report intentions to return to the program, according to the research led by San Francisco State University professor Nicole Bolter. However, one reason some parents indicated they won’t return was their belief that the program was not competitive enough and teaching proper sports skills.

“I don’t think parents see sports as either/or (for their child’s outcomes),” Bolter said. “They want it all for their child – they’ll be pro athletes and great citizens. Parents are not looking to compromise on anything.”

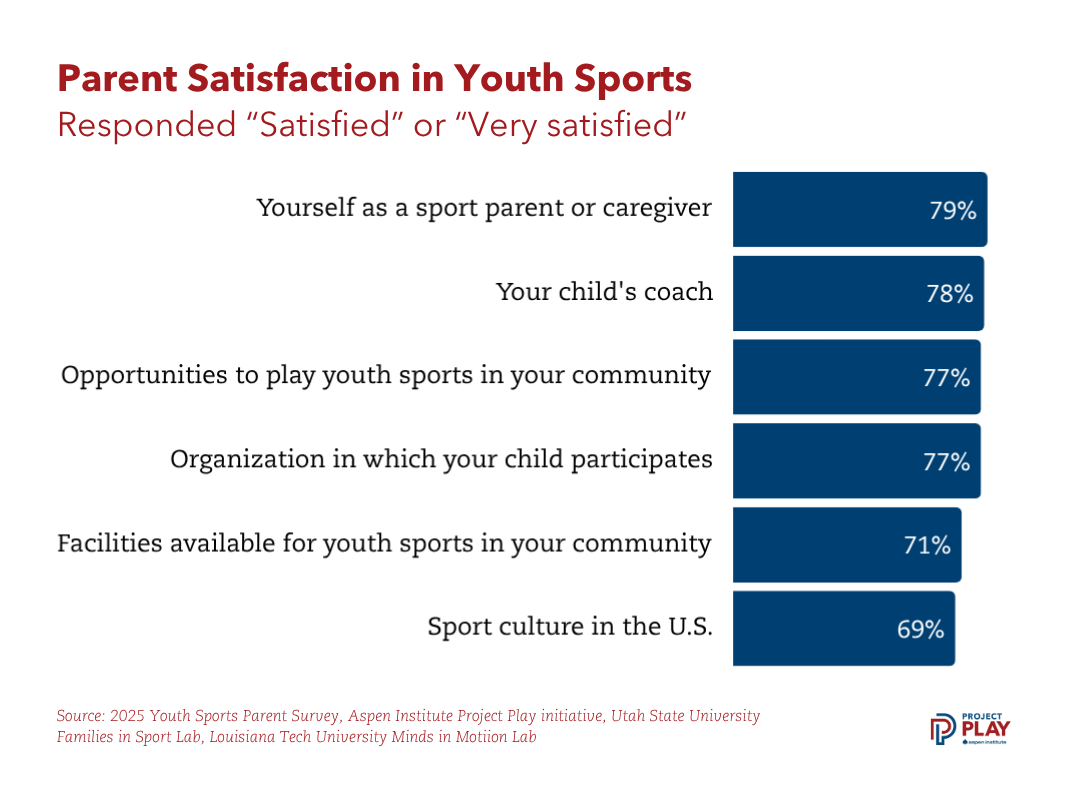

Youth sports parents generally appreciate the value of the institution. In the Institute’s survey, almost seven of 10 of them expressed satisfaction with sport culture in the U.S., Generally, parents expressed greater satisfaction with individuals and entities the closer they are to the family, including a 79% favorable rate for themselves as sports parents.

“Some coaches and sports administrators might disagree with that rating, but it strikes me as about right,” said Tom Farrey, executive director of the Aspen Institute’s Sports & Society Program and author of Game On: The All-American Race to Make Champions of Our Children. “Most parents are reasonable, try hard to check their behavior and don’t cause problems. The headaches and bad headlines are usually created by a few parents on the sideline who just lose perspective and warp the whole experience for all.“

Because society embraces sports as part of a positive childhood, parents feel like they are succeeding as a parent when their child excels in sports, Koller said. “Parents still refuse to believe this, but the best way to become an elite athlete can be having fun, participating in a range of sports, and letting kids’ minds and bodies grow up,” she said.

In the community where Mape lives, she finds many children worry that their coaches won’t play them if they make mistakes and that their parents will stop loving them if they fail.

“When children don’t want to play, we have to realize it’s about them and not us,” Mape said. “We have to connect with them in very different ways. It’s not, ‘Good job but.’ It’s just, ‘Good job.’”

Jon Solomon is Community Impact Director of the Aspen Institute Sports & Society Program. Email him at jon.solomon@aspeninstitute.org.

Survey Methodology

The Aspen Institute’s National Youth Sports Parent Survey, in partnership with Utah State University and Louisiana Tech University, utilized a nationally representative survey of 1,848 youth sports parents whose children participate regularly in one or more sports activities. The survey was conducted online in November and December 2024 with parents of children ages 6-18 from every state and the District of Columbia. The research sought to address patterns of youth sports participation, parents’ involvement in that participation, and the characteristics of the settings in which participation occurs. Read the full survey results. The Aspen Institute will publish additional analysis of the results throughout 2025.