At the outset of Project Play in 2015, we profiled a boy named Tyriq, a sixth-grader at Schaumburg Elementary – a charter school on the east end of New Orleans. The school’s halls and cafeteria are lined with banners of colleges from around the country to help the students keep their “eyes on the prize,” as the faculty put it. “I know I have to get good grades so I can play in college,” Tyriq said.

Almost all students at Schaumburg, most of them African-American, qualify for free or reduced lunch. Tariq picked up basketball at 8 years old at a neighborhood hoop, and then played one season of “park ball” – what the area residents call the parent-coached recreational leagues based in neighborhood playgrounds. He wanted to play park-ball football too, but his mother couldn’t afford the cost of equipment.

Today, we have new insights into the challenges faced by children like Tariq. Youth ages 6-18 from low-income homes quit sports because of the financial costs at six times the rate of kids from high-income homes, according to a national survey of parents by the Aspen Institute’s Project Play initiative and Utah State University’s Families in Sport Lab.

In the coming months, the Aspen Institute will release and explore more findings, which offer new insights into the causes of sport attrition. The first set of results were released in July 2019 before the launch of the #DontRetireKid public awareness campaign inspired by Project Play 2020, a working group convened through Project Play. Those results showed the average child spends less than three years playing a sport and quits by age 11.

In this post, we break down the data by family income — an important factor given that youth sports have become an estimated $17 billion industry, often leaving behind families who cannot afford to keep up with the escalating arms race. We explore participation rates, free play, pressure on kids, and costs to play by evaluating responses from low-income households (less than $50,000 in gross annual income), middle-income households ($50,000 to $100,000), and high-income households (more than $100,000).

Our nationally representative survey, distributed by Qualtrics International, collected insights from 1,032 adults in all 50 states whose children played sports. The median household income of respondents was $70,000, compared to the U.S. average of $61,937. Each of the three financial brackets that were tracked accounted for about one-third of the sample. Parents whose kids were not active youth sport participants were not sampled.

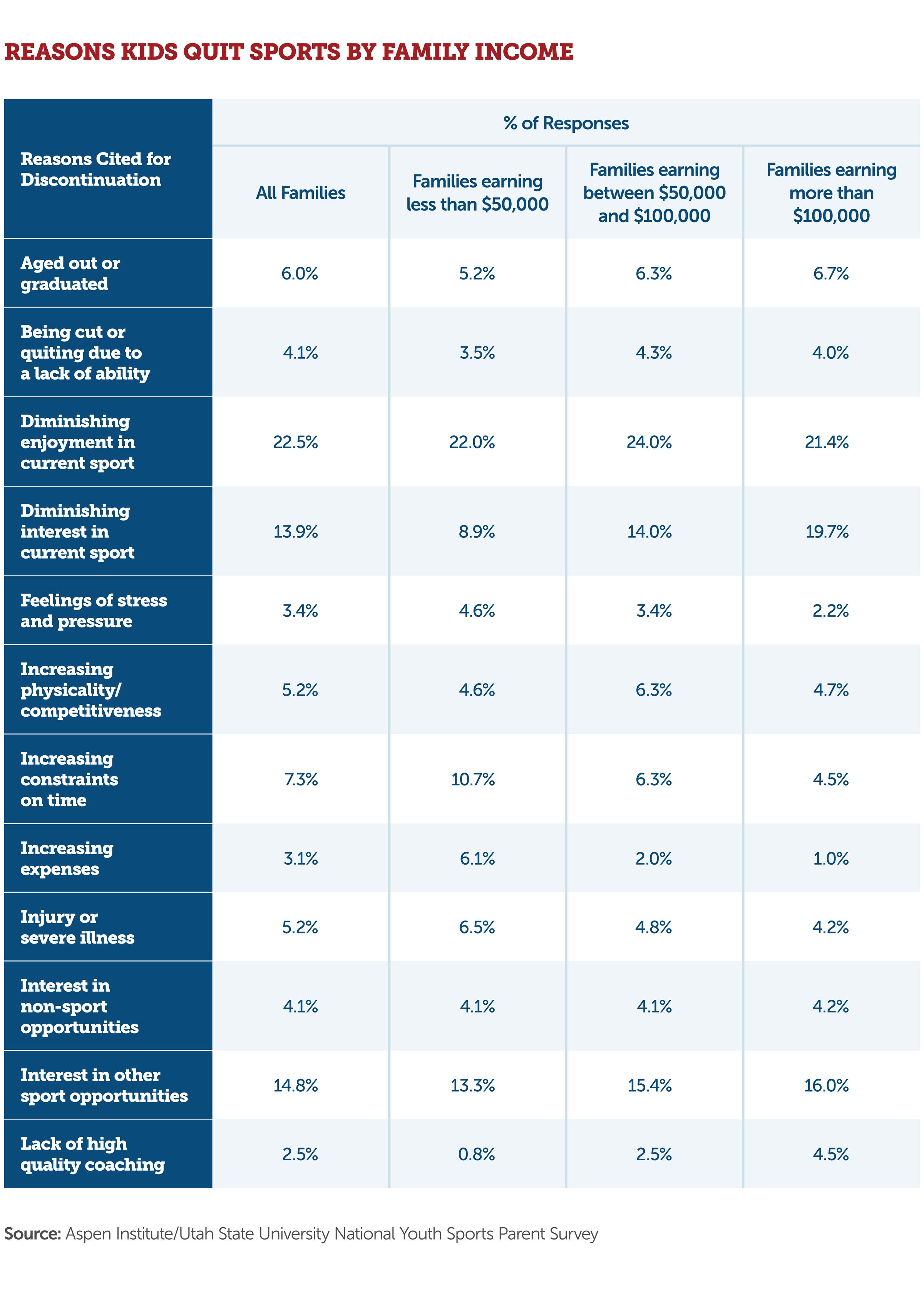

One of the main reasons poorer kids quit sports, according to our survey: time constraints. Their parents were two times more likely to cite lack of time as why their child quit sports than wealthy parents. This likely speaks to lower-income kids’ family responsibilities, such as caring for siblings or earning money from a job, and transportation challenges to attend practices and games.

However, the survey showed that the more money a family earns, the less likely the child enjoys sports. High-income parents (41%) were more likely to say their child quit a sport because it stopped being fun than middle-income parents (38%) and low-income parents (31%). Interestingly, middle-income parents were three times less likely to identify burnout as the reason for quitting than the wealthier and poorer parents.

More high-income parents said the lack of quality coaching is why their child left a sport. “This is an interesting finding because it confirms that kids from more-affluent families have more social mobility in sport,” said Dr. Travis Dorsch, founding director of the Utah State University Families in Sport Lab and lead investigator on the Aspen study. “If they don’t have a good coach, if they experience a little adversity, their parents are able to step in and find them another team, sport or coach. Less-affluent families are often time stuck with not too many options on the table.”

Other key findings from the new analysis (see related charts at the bottom of this page):

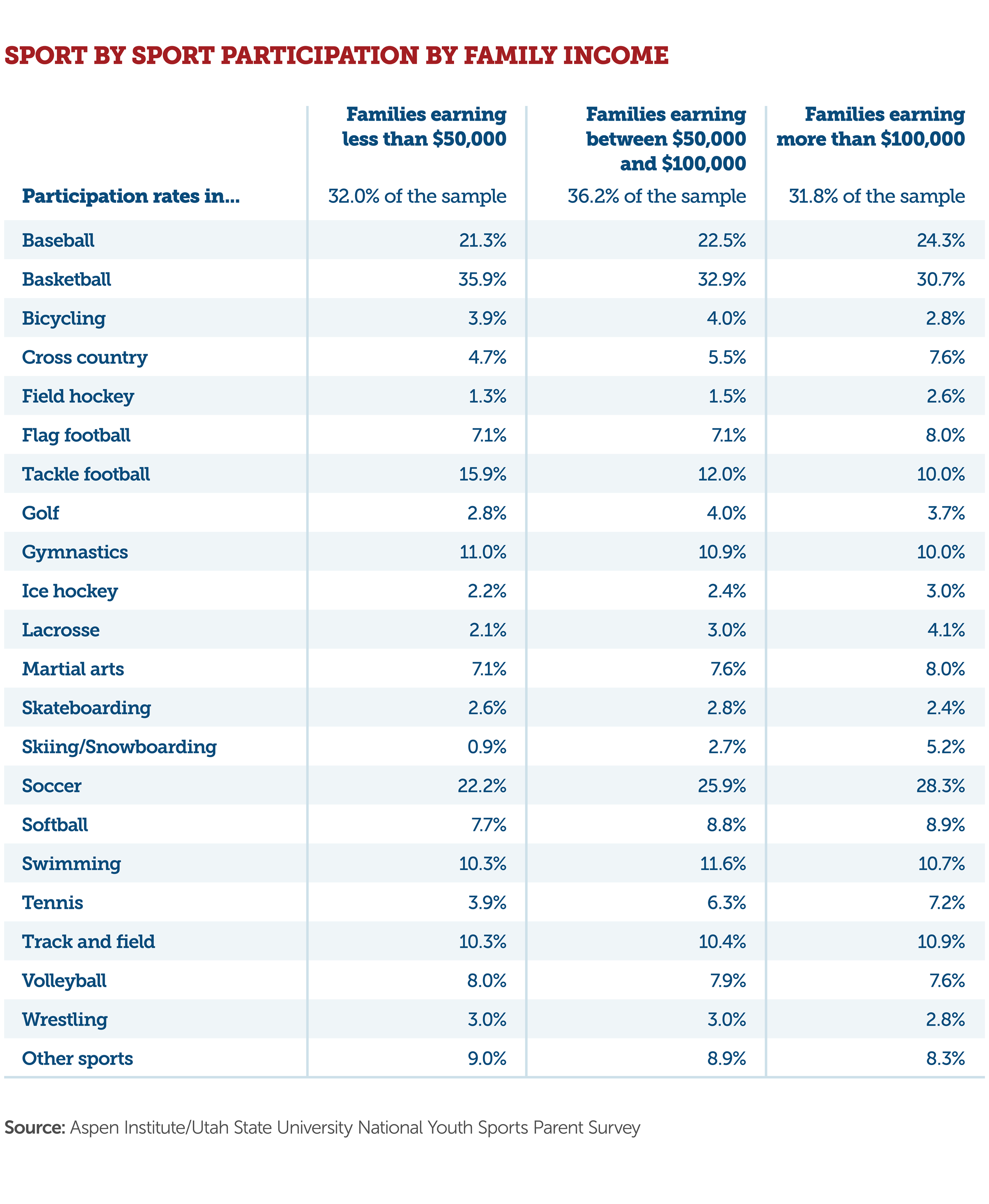

Family income shape the sports that youth play. Children from high-income homes were at least twice as likely to play field hockey, lacrosse, and tennis, or to participate in skiing/snowboarding than kids in low-income homes. Children from low-income homes were more likely to play tackle football and basketball. Children from all households participated at relatively equal rates in bicycling, flag football, golf, gymnastics, skateboarding, swimming, track and field, and wrestling. “While most sports remain relatively accessible, it is evident that certain sports are easier for low-income youth to engage in while others are more aligned with high-income families,” Dorsch said. The survey asked parents how often their oldest child regularly participates in sports, which the Aspen Institute defined as at least 35 practice, training or competition days within the previous 12-month period.

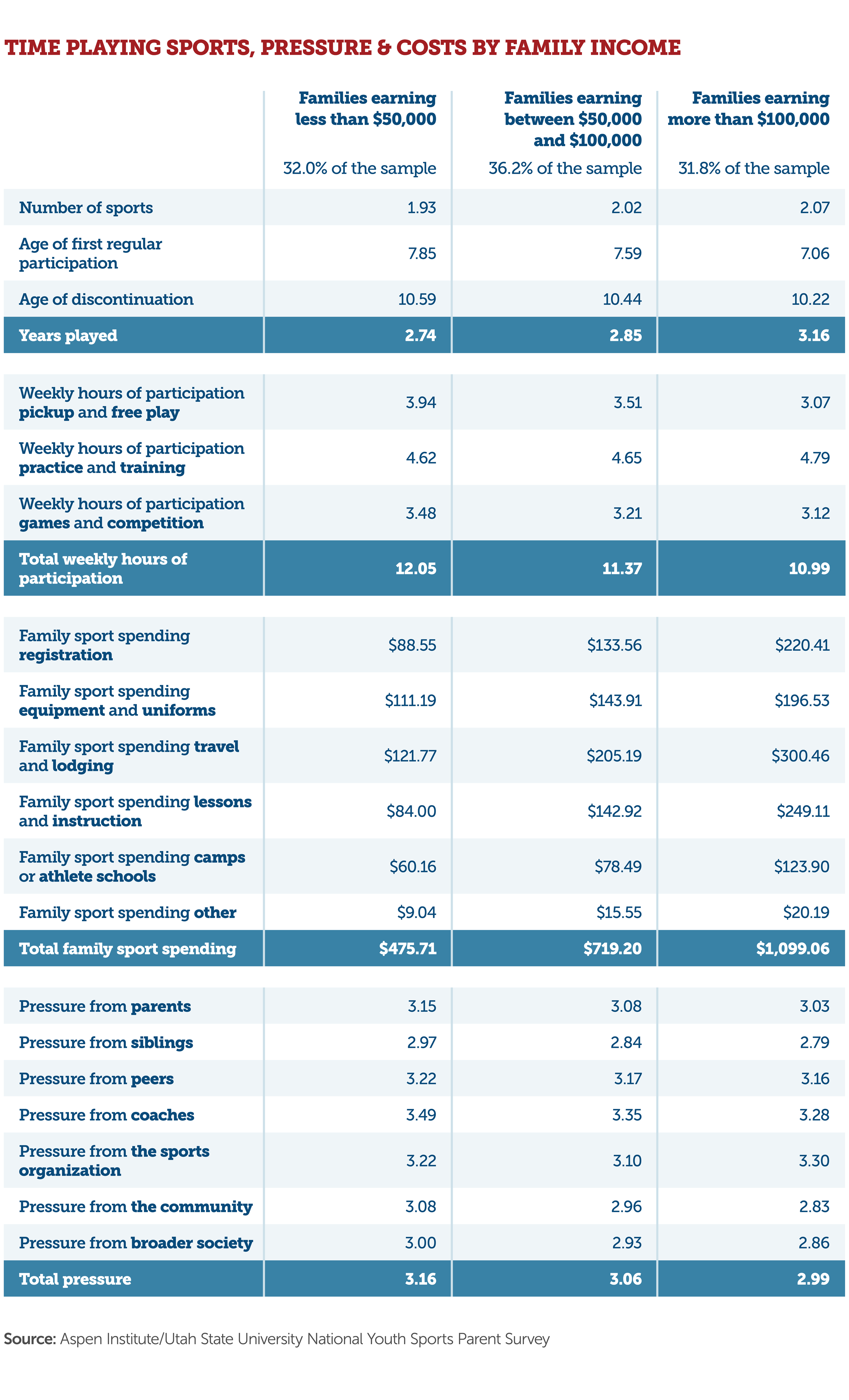

Kids from high-income homes start and end sports participation earlier. The average child in the high-income homes began regular playing sports around age 7 – almost a year earlier than the low-income youth, who stuck around slightly longer before quitting. Still, the high-income kids on average played one sport longer (3.16 years) than youth classified as middle-income (2.85) and low-income (2.74).

Poorer children who still play sports spend more hours on free play and competitive games; wealthy children participate more in dedicated practice and training. Parents from low-income households reported that their kids spend 12 hours a week on sports – one hour more than youth in the high-income homes. The biggest reason was low-income kids spend more time in pickup games and free play (3.94 hours per week, compared to 3.07 for the wealthiest kids). High-income kids spent slightly more time on practices and training (4.79 hours per week) than low-income youth (4.62).

Parents from low-income households believe their kids are more stressed. On a scale of 1 to 5, they reported their kids feel a moderate level of stress (3.16 average) while participating in sports – more so than high-income (2.99) and middle-income (3.06) families. When asked to rate what sources their child feels pressure from in sports, low-income and middle-income parents pointed the most to coaches. High-income parents reported the most stress on kids came from sport organizations.

Kids from wealthier families try more sports. The high-income parents reported that their child on average regularly plays 2.07 sports. That was higher than low-income (1.93) and middle-income (2.02) households. Project Play along with many national sports organizations and doctors encourage multisport sampling to reduce the risk of burnout and overuse injuries. Lately, there are anecdotal signs that kids may be sampling more sports – but often they are doing so in the same season, meaning their bodies and minds could still be stressed.

Wealthier parents spend much more money on sports. This is no surprise, though it’s still worth noting. The high-income households reported spending on average $1,099 annually for one child, compared to $719 for middle-income homes and $476 for low-income homes. High-income parents paid twice as much on registration fees, travel and lodging, lessons and instructions, and camps as low-income parents. “This is an important stratification,” Dorsch said, “as it provides an added and sometimes unnecessary barrier to participation for many middle- and low-income kids and their families.”

Even some kids are noticing the costs. Owen Norwood was a 10-year-old baseball player from Mobile County, Alabama when his team reached the Cal Ripken World Series in 2017 and traveled to Hammond, Indiana. The cost for each child to attend the World Series: about $3,000. Owen’s mom, Kimberly Gordon, wasn’t prepared for fees this high, so fundraisers helped them get there – something not all kids can manage.

“It’s very crazy. It’s ridiculous,” Owen said of the costs. “Maybe make sports not cost so much. Like, why can’t we not pay for the uniforms? Maybe the park can pay for the uniforms.”

Over the next year, Project Play will share and explore more findings from our national parent survey. Read Part 1 of the survey analysis. Find free tools that can be used to get and keep kids involved in sports are our new Parent Resources page. Sign up for our newsletter via the Parent Resources page.

Follow us on Twitter and Facebook as new analyses and resources are released. Do you have a question about youth sports? Send it to jon.solomon@aspeninstitute.org for consideration to publish in our monthly Project Play Parents Mailbag.