Photo: DCSAA

Meet Jasmine, a mom we spoke with during one of several focus groups with D.C. parents. Jasmine, whose name we changed for privacy reasons, needed help for her children after her husband died. Every grief counselor she called had wait lists.

“When I say I was lost, I was literally looking for anything,” Jasmine said.

Through word of mouth, she stumbled upon a one-day grief camp offered by the Nationals Youth Baseball Academy. Because her children attended the camp, Jasmine learned the academy also offers a nine-month program that, through trained coaches and staff, has since helped her children cope with their emotions. She was lucky to find the right program. Many do not.

“You learn by random social media posts and word of mouth,” Jasmine said. “I used to drive around and see the signs (for sports programs).

The marketing is not there anymore. If you don’t get it from another parent, you’re just not going to get it. And if you do get it, you probably missed the deadline to register.”

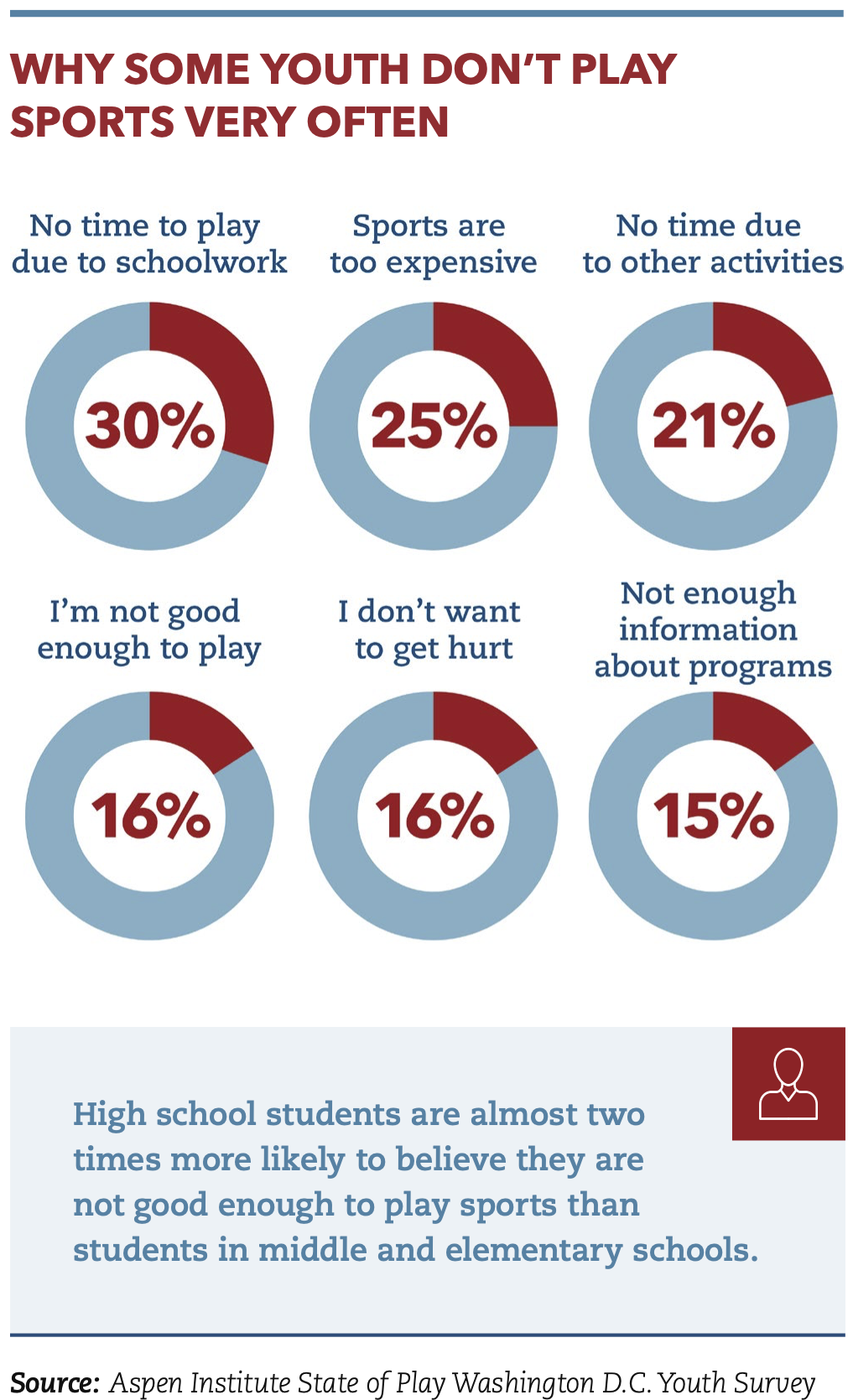

Young people notice this challenge too. In our youth survey, children who indicated they don’t play sports very often cited lack of program information — it was the sixth-most-popular reason among 16 answer choices.

Low- and medium-income youth are two to three times more likely than the wealthiest children to lack enough information on sports programming.

The District’s Out of School Time initiative (OST) has a program finder that includes sports activities such as basketball, baseball, cheerleading, bowling, flag football, soccer, running, volleyball and tennis, plus other types of extracurricular activities. The sports programs are often connected to life skills (like poetry, behavioral support, academic tutoring, nutrition, leadership, character development and conflict resolution).

OST often hears from families that they lack a streamlined way to learn about programs. So, it’s investing several million dollars to develop a platform launching in 2025 to better search for activities beyond the current directory of afterschool grantees.

The portal will include information such as whether the activity is free or costs money, how many spots are available, and how to apply or indicate interest in a program.

District officials hope to include activities at public schools, public charter schools, DPR and other entities — including organizations that are not funded by a government agency. They expressed interest in adding public or private sports programming to the directory in future years.

Solution: Create a youth sports online directory of programs for multiple uses

A good example for D.C. to learn from is the City of Boston, which launched the Boston Youth Sports Directory and Boston Sports Facilities Map in 2024 to help families locate nearby facilities and organizations and for government analysis. The District might operate a directory differently, and creating it could be a joint effort through a D.C. Athletic Council. Still, Boston’s directory offers a glimpse of its benefits and challenges.

More than 300 organizations of all sizes — both for-profits and nonprofits — are in the Boston Youth Sports Directory, accounting for an estimated 60% of providers in or near the city limits. Families can search for the sports organizations that make sense to them, using filters by sport, age, neighborhood, season, gender, competitive level of the activity, language and cost. Schools are not included in the public-facing database because their information was incomplete and city leaders wanted the activities to be open to anyone, unlike school sports that often require tryouts.

Clicking on organization names in the directory reveals additional information about them. Do they conduct safety training for coaches? Do they offer transportation support? Do they carry insurance? Do they provide equipment for athletes? Do they conduct background checks on coaches? Do they make accommodations for differently abled youth? Organizations can also describe on their page who they are, their costs, registration timeline and process, extra enrichment opportunities (such as academic tutoring), and who to contact.

Not only can the directory help families, but it also helps the city focus more on the community’s needs and communicating opportunities.

Boston uses the directory to share information about grants, events and coaching development, and evaluate how government and other potential funders can help. Learn more about Boston’s efforts at as.pn/BostonDirectory.

Fight For Children, a local youth-development sports organization, has considered building a somewhat similar directory in D.C. to help families of its nonprofit partners search for programming by sport, geography and youth development components such as mentoring and academic tutoring. Several sports providers in D.C. said such a directory would be valuable.

“I wouldn’t understate the importance of building a platform so people could identify a program like ours,” said the director of a small sports club that includes youth development components.

“It would be knowledge and information that can serve as the starting point to address a lot of these inequities with access to quality sports opportunities. At the same time, it could be difficult for some providers to keep up with new demand from this new exposure on a directory without more funding to build the capacity to serve more children.”

In addition, the District’s existing Youth Sports Day could be built out to include partners of the D.C. Athletic Council, which would expose more families to sports programming. In 2024, the annual event hosted by Fight For Children brought nearly 2,000 attendees to The Fields at RFK, where kids participated in sports and received free backpacks, school supplies, health exams and haircuts.

Jon Solomon is Community Impact Director of the Aspen Institute’s Project Play initiative. Jon can be reached at jon.solomon@aspeninstitute.org.