Photo: Fight For Children

The following article was originally published in the Aspen Institute’s State of Play Washington D.C. report. The report assesses the opportunities and barriers for more children to access sports and physical activity in our nation’s capital.

Black children in D.C. played sports at a higher rate (51%) than the U.S. average (45%) in 2022 and 2023, according to the National Survey of Children’s Health. But the gap compared to White participants in D.C. (33 percentage points) was far greater than it was nationally (18 points).

Wards 7 and 8 are historically the most underserved communities in the District. They skew younger, more Black and lower income than the D.C. average. The highest number of young people live in Wards 7 and 8, representing 37% of D.C. residents who are under age 18.

Children in Wards 7 and 8 played at least one sport in the past 12 months at relatively lower rates than every other ward, according to predictive analysis by Kinetica. Participation in almost every sport or physical activity, except football and basketball, is lower in Wards 7 and 8 than in Ward 3, which is the most affluent area of the District.

Yet the demand exists to play sports. Compared to all of D.C., Wards 7 and 8 have a higher percentage of parents with children who don’t play sports but expressed interest in their child participating, according to Kinetica.

Costs are the biggest challenge. Parents in Wards 7 and 8 expressed a higher level of agreement with the statement, “I am reducing the amount I spend on sport and recreation due to cost-of-living pressures,” than parents in the rest of the District.

“It’s definitely a financial strain,” said a mom of a youth football player. “It’s easily $500 per football season with all the extra costs. That’s tough.”

Transportation is also a major barrier. District children from low-income homes are driven to sports activities by family members at much lower rates than high-income youth, according to our youth survey. Children from low-income homes are three times more likely to use public transportation for sports than their high-income peers.

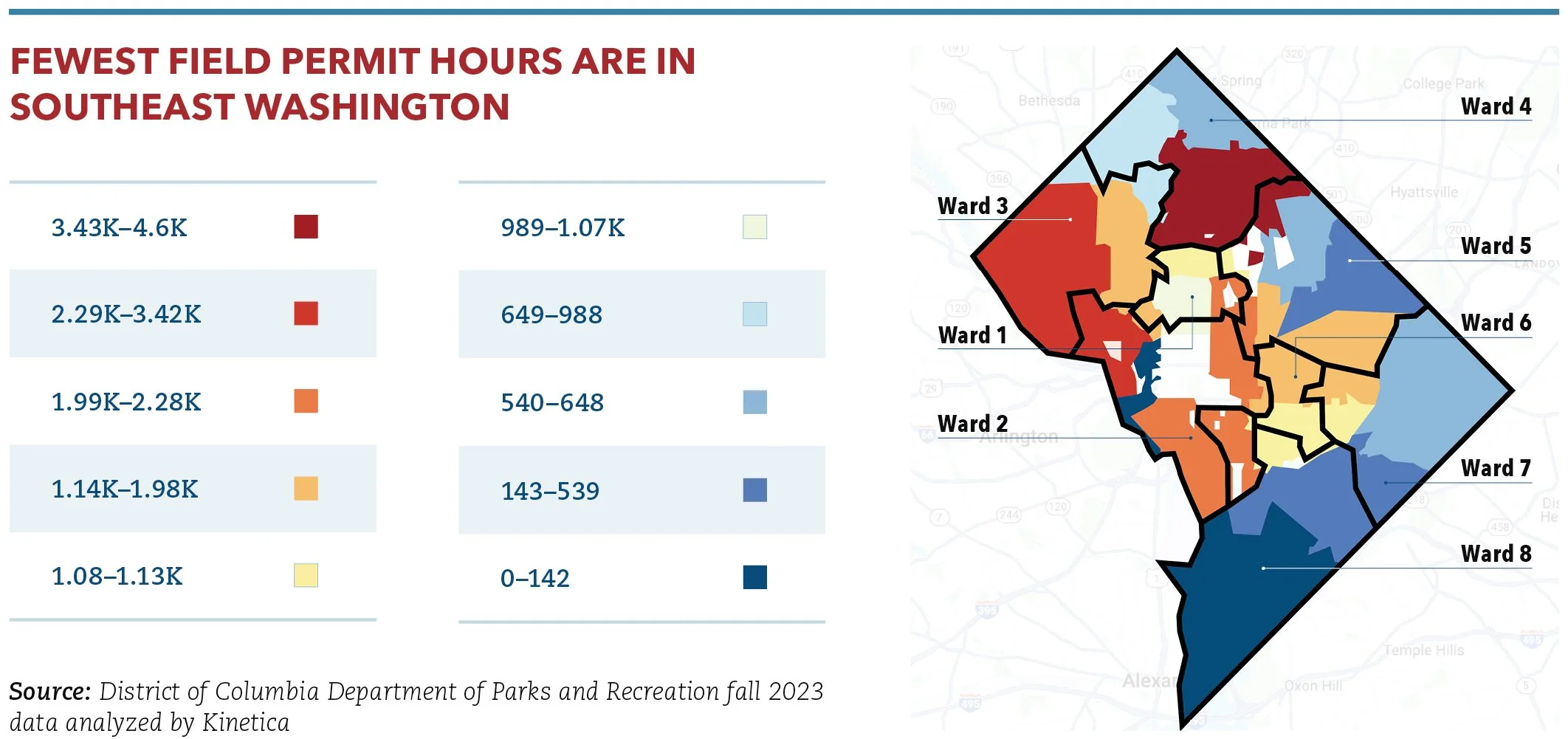

Another barrier in Wards 7 and 8 is access to quality fields. In fall 2023, 15 of the 20 most- permitted DPR fields throughout the District were in the more affluent areas of northwest Washington, according to DPR data analyzed by the Aspen Institute. None of the 20 most-used fields by permit hours were in Wards 7 or 8.

Children in Wards 7 and 8 also have fewer opportunities to continue playing sports as they get older. High schools in Wards 7 and 8 average about two fewer sports offered than the rest of D.C. No public high school in Wards 7 or 8 offers soccer, even though our analysis by Kinetica shows that soccer is the third-most played sport in the city. At all other D.C. public high schools, 71% of them offer soccer.

“We have to address that in some places the pipeline doesn’t continue. It just stops,” said Zoe Wulff, community relationships manager for the Washington Spirit. “What sort of pipeline are we building? Are we building a pipeline for kids who are incredibly talented and are being recruited by big colleges, or a pipeline for kids and adults who know how to play recreationally as they age, not just as a 10-year-old? That’s one of the biggest sticking points for youth sports in general.”

Solutions

Efforts exist to provide quality sports opportunities in Wards 7 and 8. More investment is needed, especially through sustainable funding, strategic community partnerships with schools and bringing sports near where children live to reduce transportation challenges.

Two soccer organizations – one well established, one up-and-comer – offer intriguing models for others in the District to emulate no matter the sport. They intentionally teach life skills off the field, not just soccer.

DC SCORES

DC SCORES represents what a sustained, legacy project from a major sporting event (the 1994 World Cup held in D.C.) can produce. By focusing on youth development as much as soccer, partnering with local pro teams and operating within schools, DC SCORES opens doors for more children to play sports and develop as young people.

DC SCORES is a member of the Fight For Children Leadership Council and serves more than 3,000 District children, at 64 elementary and middle schools with free soccer, poetry, and service- learning programs in seven of D.C.’s eight wards. Typically operating in Title I schools with high rates of poverty, DC SCORES has a heavy footprint in Wards 7 and 8. Its parent organization, America SCORES, reaches over 20,000 students nationally.

During the fall, beyond practicing and competing in soccer matches, DC SCORES kids work with writing coaches to compose poetry about their passions and the world through their eyes. In the spring they translate the poems into a service- learning project to help their communities. Projects include neighborhood and school cleanups, raising money for the homeless, and awareness campaigns about immigration rights, suicide prevention and gun violence in schools.

Schools serve as an equalizer of sorts to help lower-income children play sports, even though many children in D.C. change schools during their academic career. Since D.C. schools do not provide busing for students to attend school, DC SCORES spends $500,000 to $600,000 annually to help transport children to activities.

“We consistently hear from families that transportation is the biggest barrier,” said Katrina Owens, executive director at DC SCORES. “Many of our kids travel from school from a different neighborhood than where they live, so ensuring that consistency and access to play spaces is critical. Utilizing teachers and staff from within the community to lead them has also been a powerful connector because families already know those people. They trust them.”

DC SCORES has a waiting list of 14 schools that want to join. “The goal is once we’re in a school, we stay there forever,” Owens said. “Even if a kid moves schools within Ward 7, there’s a good chance they’re going to be in a DC SCORES school and can find a home in a new building.”

Open Goal Project

In 2015, former MLS player Amir Lowery and former DC Scores coach Simon Landau started Open Goal Project, helping dozens of D.C. youth soccer players overcome financial obstacles, transportation challenges and logistical hurdles to play club soccer in more affluent communities. Then they came to the realization that the existing American youth soccer model was not working for these kids.

“The system has to be there in their communities, just like it’s in everyone else’s community,” Lowery said of underserved children.

In 2019, Open Goal Project launched the District of Columbia Football Club (DCFC), a fully funded soccer club that’s completely free for players. Rather than making children travel to affluent suburbs on teams with excessive costs and different cultural environments, Open Goal Project brings resources to the children.

Landau said the equity gap in marginalized D.C. communities is not about access to rec soccer, but rather club soccer. With largely Black and Hispanic players from lower-income homes, DCFC competes against clubs with predominantly White, upper-middle class players. “The impact on kids removed from their community and getting socially and emotionally dumped into a situation where they don’t feel safe or relatable to coaches and teammates was really core to building this,” Landau said.

Open Goal Project is a member of the Fight For Children Leadership Council and serves 500 D.C. children between its tryout-based club team, summer and college identification camps, and an in-house rec league through MLS GO for kids ages 5-12. Open Goal Project plans to start programming in Wards 7 and 8 in 2025.

All of Open Goal Project’s practices are intentionally held within walking distance of public transportation. DCFC plays an independent club schedule to mitigate travel costs within manageable distances. Bilingual coaches help assimilate the club’s players who speak Spanish.

“I tried out for a club team in Arlington (Virginia) and there was not a single Black or Hispanic,” said an 18-year-old Hispanic girl who plays for DCFC. “I felt like if I said something wrong, they would say I should leave.”

Lowery and Landau acknowledge that their model of free club soccer may not be replicable everywhere. Their total program costs about $550,000, and they’re trying to scale up, piecing funding together through DME and DPR grants, relationships with the Mayor’s Office on Latino Affairs, and individual donors and sponsors. Open Goal Project also offers academic tutoring, mentorship, SAT prep, college counseling, health and wellness support, and Friday night events in a safe and supervised environment.

“Youth sports alone isn’t going to drive funding for sports providers to succeed,” Lowery said. “You have to build a holistic program that will address community needs and attract funding sources that are available.”

Jon Solomon is Community Impact Director of the Aspen Institute’s Project Play initiative. Jon can be reached at jon.solomon@aspeninstitute.org.