Participation Trends

The trends below come from the Aspen Institute’s State of Play 2025 report, informed by interviews with leaders in the youth sports space, data analyzed by the Project Play team, or articles and research produced by other entities.

1

Fourteen states reached the 63% sports participation target

The federal government has a national public health goal for youth sports participation to reach 63% by 2030, an effort being championed by Project Play through our 63X30 roundtable organizations. There was progress in 2023 – the most recent year of data. Across the country, 55% of youth played organized sports, up from 54% in 2022, according to the National Survey of Children’s Health.

Progress was made as 14 states and the District of Columbia reached the 63% mark – Vermont (72%), South Dakota (69%), New Hampshire (68%), Massachusetts (65%), Iowa (65%), Minnesota (65%), Washington D.C. (65%), Colorado (65%), North Dakota (64%), Nebraska (64%), Rhode Island (63%), Wyoming (63%), Maine (63%), Hawaii (63%) and Montana (63%). Kansas, Wisconsin and Illinois were within one percentage point of 63%. Thirty-four states increased their participation in 2023.

Nevada (43%) had by far the lowest participation rate, followed by Delaware, Florida, West Virginia and Texas. Each of those states ranked among the lowest for female participation.

2

Casual forms of organized play are surging

Over the past year, something pretty significant quietly happened – 6% more children ages 6-17 played a team sport at least once in 2024 compared to 2023. No matter the age, casual participation was up 6%-7% for both the 6-12 and 13-17 age groups. All told, 65% of youth 6-17 tried sports at least once in 2024 – a significant jump from 59% in 2021 and the highest on record tracked by the Sports & Fitness Industry Association dating to at least 2012.

“For the last five years, we were expecting growth and it’s nice to finally see it,” said Alex Kerman, SFIA senior director of research operations and business development.

Meanwhile, core sports participation (i.e. playing on a regular basis) increased for the third straight year for kids ages 6-12. And for the second straight year, regular sports participation for kids 6-12 reached its highest level since 2015. However, teenagers ages 13-17 continued to regularly play sports at lower rates, with their participation dropping by 3% in 2024.

Coming out of the pandemic, SFIA had seen increased physical activity and sports participation among adult Americans, but it had not trickled down to youth until 2024. Kerman said the pandemic fundamentally changed how Americans think about physical activity, including how sports get offered to children in more casual and infrequent settings, such as the NFL’s investment in flag football with RCX Sports.

“You’re seeing this big change in how pro leagues are offering sports to children,” he said.

3

Participation among Latinos grew faster than any demo

For many years, Latino youth played sports at lower rates than their peers. That changed in recent years based on annual data Aspen tracks from SFIA.

In 2024, 65% of Latino youth ages 6-17 tried sports at least one day over the previous 12 months – a higher rate than Black and White youth, according to SFIA data. ELLA Sports Foundation co-founder Patty Godoy attributes the increase to greater representation of Latinas in college and pro sports. “When young girls feel represented, they are empowered to dream and to succeed in life,” Godoy said. “This representation is inspiring and motivating for young Latinas to play sports and stay in sports.”

Participation among Latina girls rose from 39.5% in 2019 to 48.4% in 2024, outpacing the growth of their non-Latina peers, according to “Unlocking the growing power of Latino fans,” new research published by McKinsey Institute for Economic Mobility. The report attributes this success to the work of many organizations – such as ELLA Sports Foundation, Girls on the Run, Sports 4 Life and the Women’s Sports Foundation – that have launched programs targeting historically underrepresented groups.

Still, there are challenges. Latino parents cite scheduling conflicts more than non-Latinos as a barrier for their child to play sports, according to SFIA. Also, research by McKinsey and U.S. Soccer Federation found that Latino and Black children are three times more likely than White children to stop playing soccer because they feel unwelcome.

Latino youth still regularly play sports at lower rates than White youth based on SFIA’s core participation statistic, which tracks the number of times someone plays team sports many times in a given year. But since 2019, Latino youth regularly played sports at higher rates than Black youth in all but one year – a change from more than a decade ago.

It remains to be seen what impact, if any, current immigration raids may be having on Latino sports participation rates that appear in future analysis. Schools are seeing increased absenteeism. For example, a study by Stanford University found that recent raids in California’s Central Valley coincided with a 22% increase in daily student absences.

“It’s affecting our community-based (sports) programs and parks programs. It’s not a surprise,” LA84 Foundation President & CEO Renata Simril said in a conversation about community wellness in sports hosted by the Aspen Institute Latinos & Society Program.

Sports participation for Latina girls rose over the past five years, outpacing non-Latina peers. (Photo: Getty Images)

Throughout 2025 and into 2026, media accounts documented many fears due to immigration raids.

A youth baseball coach in Manhattan said a group of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents approached members of his team while they were practicing in a park, resulting in the coach defending the legal rights of his players.

In Los Angeles, attendance was down across summer sports programs in parts of the city after immigration raids.

Soccer Without Borders, which provides immigrant children with opportunities to play soccer, reported some players are staying away in the Bay Area over fear of ICE arrests.

In Kenner, Louisiana, the Jambalaya Soccer Academy paused programming in November 2025 when only about 10 of 120 children were showing up due to parents’ fears about local Border Patrol operations. The academy did not reopen in January 2026 as planned.

The Oregon Youth Soccer Association (OYSA) announced that as many as 16 teams withdrew from competition in Portland after people reported ICE activity in community parks.

“People will have different views about immigration and enforcement actions – and that’s understandable,” OYSA Executive Director Simon Date wrote to parents. “But wherever you stand on the politics, we stand unapologetically with kids not being scared to be at our events. Every child deserves to play soccer without fear, and that will always be our north star.”

4

Girls flag football and boys volleyball are exploding

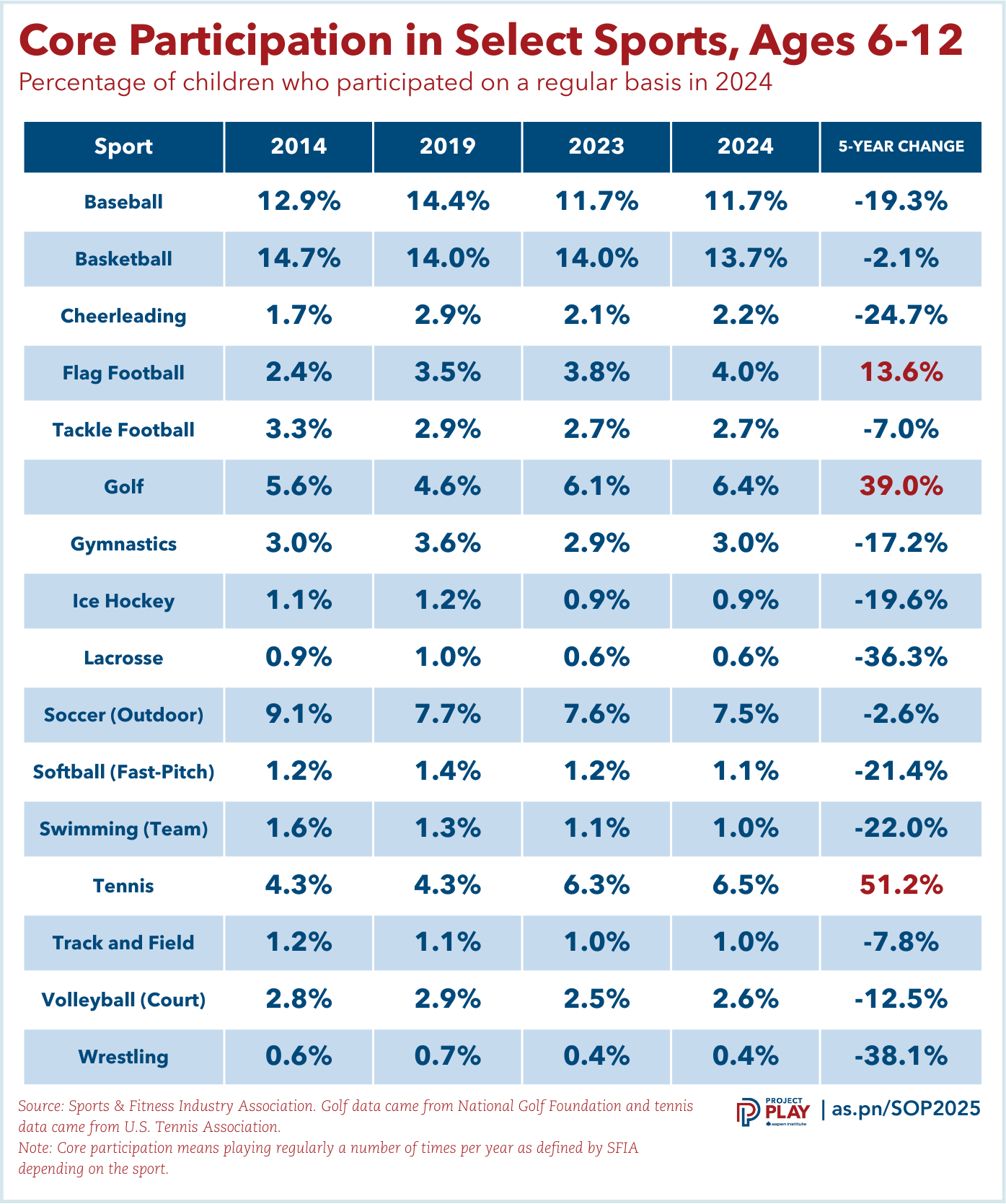

In the decades to come, we may view youth sports as two eras – before flag football exploded and after. We’re currently in the early stages. Consider what happened from 2019 to 2024: flag football was the only team sport tracked by SFIA that experienced growth in regular participation among kids ages 6-17. (Tennis and golf increased as individual sports through separate data shared with Aspen.)

Baseball was down 19%. Tackle football was down 7%. Soccer was down 3%. Basketball was down 2%. Flag football? Up 14%.

In 2017, flag surpassed tackle as the most commonly-played form of the game for kids 6-12. The gap continues to widen at that age, with 4% playing flag in 2024 vs. 2.7% playing tackle. Among youth ages 13-17, it’s important to note that tackle (6.4%) is still much more popular than flag (2.8%). And the number of high school 11-man tackle participants increased in three of the past four years – a trend not seen since the mid-2000s.

At younger ages, tackle football is not the only sport impacted by flag. Within soccer circles, some leaders privately worry that flag football is pulling away would-be soccer players. In 2012, soccer participation exceeded flag participation among kids ages 6-12 by 6.4 percentage points, and by 2024, soccer’s advantage was down to 3.5 percentage points.

Flag’s growth is largely attributed to the NFL, which has invested in the sport more as some parents delayed or walked away from tackle due to the risk of brain injuries and shifting U.S. demographics. NFL FLAG serves more than 620,000 youth ages 4-17 in 50 states. The NFL has also campaigned to bring flag football to high schools for girls, and 28 states now either sanction girls’ high school flag or are in various stages of pilot programs.

Soon, kids will see their idols playing the sport. In October, the NFL announced plans to launch women’s and men’s professional flag leagues in the next couple years ahead of flag debuting at the 2028 Los Angeles Olympics. “The demand is there. We’re seeing colleges in the states and universities internationally also that want to make it part of their program,” NFL commissioner Roger Goodell told reporters. “If you set that structure up where there’s youth leagues, going into high school, into college and then professional, I think you can develop a system of scale. That’s an important infrastructure that we need to create.”

Future infrastructure will need to include developing a pathway for boys to continue playing flag into high school. Currently, the opportunities dry up for boys because high schools focus on tackle. How leaders handle flag’s meteoric rise will be fascinating to observe. Will coed and affordable grassroots opportunities remain? Will tackle football benefit from the rise of flag? Will America’s highly commercialized youth sports industry produce more costs, time commitment and pressure for kids to specialize in flag? Will coaches be trained to minimize injury risks, given that cut-and-pivot sports have the highest rates of ACL tears? Or can the sport avoid the pitfalls felt by other sports and create health-promoting, inclusive structures?

Flag football continues to outgrow tackle football among ages 6-12. (Photo: Tacoma Public Schools)

Meanwhile, volleyball participation is growing faster than any other high school boys sport, with a 13% increase in 2024-25, according to National Federation of State High School Associations. Boys roster numbers increased by 51% over a six-year period, reaching 95,972 spots in 4,303 schools during 2024-25. Volleyball is nearing the top 10 of the most-played high school sports by boys, trailing No. 10 swimming and diving by 23,000 roster spots. A decade ago, the gap was 83,000 between volleyball and swimming among boys.

What’s changed is a partnership between the First Point Volleyball Foundation and American Volleyball Coaches Association to help sanction volleyball in new states. Over the past six years, nine states have added varsity boys volleyball: Oregon, Kentucky, Indiana, Utah, Colorado, Michigan, Minnesota, South Carolina and Missouri.

In Oregon, after the sport was sanctioned in 2025, Portland Public Schools elected not to add volleyball as a varsity sport, citing budget issues and Title IX concerns. Dozens of high-school age players attended a school board meeting and tried to convince the district to change its mind. As of late 2025, the plan is for Portland schools to remain club volleyball teams, not state-sanctioned varsity teams.

“It’s hard to explain how important this sport and community is to so many people (across the school district),” volleyball player Jack Coracci told the board. “But it’s really not just about us right now. There are so many kids that will try volleyball and fall in love, just like I did, so to strip that opportunity away from them is disheartening. It’s hard to think about. All we want to do is play, so let us play.”

5

Lack of access among low-income youth is limiting growth

Too many children are still left behind and the gap is growing. In 2012, 35.5% of kids ages 6-17 in homes with incomes under $25,000 regularly played sports vs. 49.1% who played from homes earning $100,000 or more – a difference of 13.6 percentage points. By 2024, the gap was 20.2 percentage points, according to SFIA data.

Boys 6-17 regularly played sports in 2024 at their highest level since 2015, marking a 2% increase over one year. It was the second straight year boys participation ticked up. Still, boys participation has resided at 42% or lower for nine straight years after half of all boys regularly played sports as recently as 2013. The Aspen Institute and American Institute for Boys and Men are studying the trend to identify the causes and potential solutions.

Girls participation, while still trailing boys, increased for the third straight year. The 2024 rate of 37% was the highest for girls tracked by SFIA since at least 2012.

Federal data tells a similar story about disparities due to wealth. Children from the lowest-income homes played sports in 2023 at half the rate of those from the highest-income group.

Meanwhile, the Aspen Institute’s national survey of youth sports parents found that children from the wealthiest households play their primary sport more frequently than their peers in community-based settings, schools, travel teams and independent training. Children from homes earning $100,000 or more are two times more likely to play travel sports than those in homes making under $50,000.

Another way children experience sports differently due to wealth is free play. Free play means unstructured or casual play – situations where kids make up their own games and play with friends for hours on end, largely absent of adult-led competition or rigid scheduling.

In recent decades, the loss of free play has been cited as costing children opportunities to exercise creativity, set and achieve goals, learn problem-solving without adult intervention, and develop a love of play for its own sake. Children from the lowest-income homes and those in urban environments engage in free play more than the wealthiest children and those living in the suburbs. Boys and younger children also participate in free play at higher rates.

Free play is also healthier. Researchers believe that overuse injury risks do not appear to be strictly related to the volume of activity, but perhaps are more related to the type of physical activity. The unstructured movement patterns in youth athletes during free play may counteract the repetitive movements of specialization, promoting more balanced neuromuscular strength and development, which may be protective against injury.

More free play is especially needed for female athletes, who have higher rates of overuse injuries and sport specialization than males. The same national research shows females participate in fewer free play hours per week and play their main sport for more months of the year than boys. The percentage of athletes that exceed the recommended 2-to-1 ratio of organized sport to free play hours is significantly higher in females (90%) than males (79%).