Photo: Getty Images

The Aspen Institute’s Project Play initiative partnered with Utah State University and Louisiana Tech University to survey youth sports parents, releasing in March 2025 with a 148-page report that helped inform several sessions at Project Play Summit 2025. Now, we’re analyzing key findings in depth. This fifth story in our year-long series examines the time commitment that parents spend on sports.

If you’re the parent of a child in sports, chances are your life gets extremely hectic. It’s not just the extra costs with sports, although a 46% increase on family spending since 2019 that surpassed U.S. inflation leaves parents frustrated. It’s also their time commitment.

Being a sports parent almost equates to holding a part-time job.

The average sports parent spends 3 hours, 23 minutes every day their child has a practice or game, according to the Aspen Institute’s parent survey in partnership with Utah State University and Louisiana Tech University. That’s time spent driving and attending activities, washing uniforms, maintaining equipment, preparing meals, talking with their child about their sports experiences, and communicating with coaches and other parents.

As sports resume for many families this fall, the time needed to be a sports parent is about to intensify again.

When a child’s primary sport is in-season, children average almost three days each week spent on coach-led practices, two days on individual practice or training, two days playing on their own, and almost two days on games or competition. That adds up to the equivalent of nine days of sports – which feels right for some parents trying to navigate a seven-day week.

“The daily grind for parents is real and amounts to a second or third shift in many cases,” said Travis Dorsch, co-author of the Aspen Institute parent study and founder of the Families in Sport Lab at Utah State University. “It’s not uncommon for a parent to get off work at five and spend two hours chauffeuring a child to practices and competition, then have to come home and prep meals, do laundry, organize equipment – all in time to get to bed late and start all over again in the morning.”

The fact that children’s activities count on this much of parents’ time “speaks to a deeply dysfunctional enterprise,” said Linda Flanagan, author of “Take Back the Game: How Money and Mania Are Ruining Kids’ Sports – and Why It Matters.”

“For ordinary households, this much time must be burdensome,” she said. “But for low-income households, and those with working parents and multiple children, such outlays are prohibitive, revealing how exclusive pay-to-play sports truly are. By any normal measure, this much time devoted to any activity on the part of grown-ups constitutes a part-time job. Any youth sports organization, league or school that expects this much from parents is doing it wrong.”

The intensity of the youth sports life for some families is reflected in another finding: children ages 11-14 average slightly more days playing games in their primary sport than those who are 15-18, and children ages 6-10 play the same number of games as teenagers. That’s contrary to the American Development Model, which recommends that children under 12 should focus on diverse sports and play, with limited structured practice hours, while older children and teens can increase participation hours gradually.

The number of sports days are even more for parents of kids who play on multiple teams in the same season, or those with more than one child playing sports simultaneously.

“I am nothing but a Uber all day long,” said a mom who drives three of her children to sports activities across Portland, Oregon.

Not surprisingly, parents from the highest-income homes spend 30% more time driving their child to practice and games than the lowest-income parents, some of whom work multiple jobs, can’t get off work or don’t own a vehicle. White parents spend 39% more time driving their child to sports than Black parents and 17% more time than Hispanic/Latino parents.

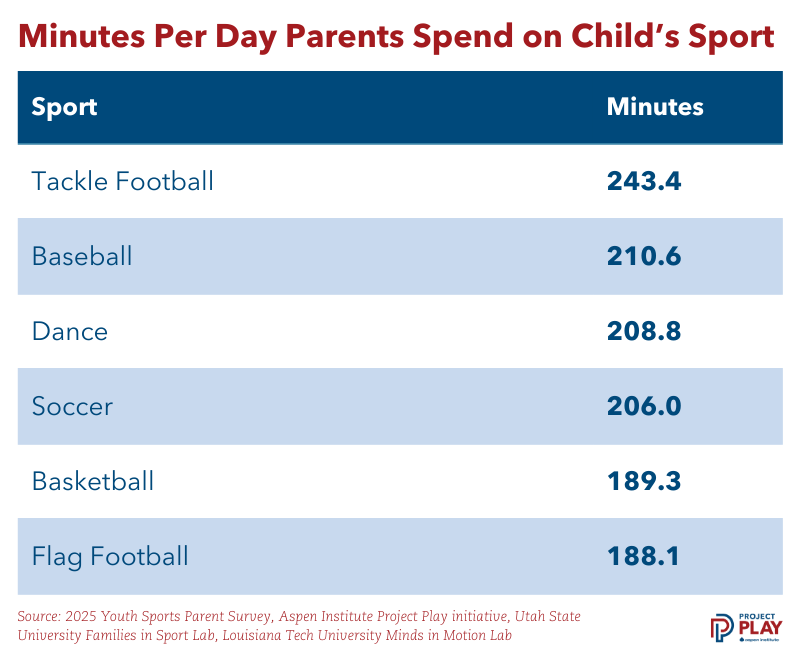

Parents of children ages 15-18 invest more time (223 minutes) than those with children ages 6-10 (179 minutes). Rural parents report spending more time on their child’s sports activities (225 minutes) than suburban parents (208 minutes) and urban parents (189 minutes).

“For rural families especially, this significant time investment reflects more than dedication; it’s born from practical necessity,” said Jordan Blazo, co-author of the parent study and associate professor of kinesiology at Louisiana Tech University. “With fewer local facilities and specialized coaching options available, these families are likely facing longer commutes and greater logistical challenges, making their commitment all the more remarkable.”

Tackle football parents reported spending the most time on their child’s sports activities during the season. It’s almost one hour more per day than flag football parents. This factors in time spent at practices and competitions, communicating with other parents, talking to their children about sports experiences, and laundering equipment or uniforms.

6 in 10 sports parents volunteer in some way

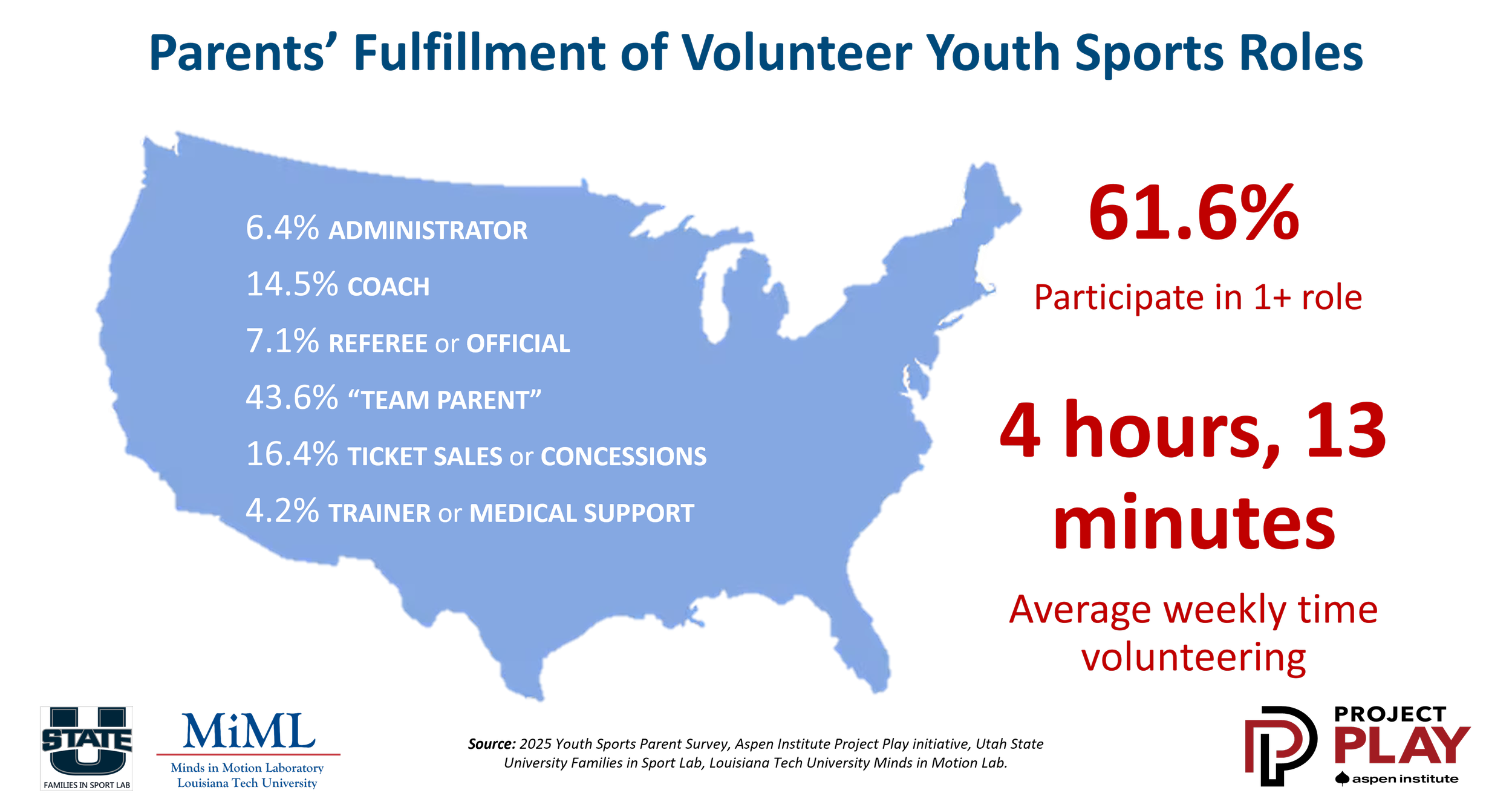

Being a sports parent can also mean giving your time to help the team. In Aspen’s recent survey, 62% of youth sports parents said they volunteer in some capacity with their child’s teams or clubs, averaging more than four hours each week. The most common role is “team parent,” a term parents were allowed to self-define what that meant to them.

Although coaching is a vital volunteer role in sports, slightly more parents reported helping with ticket sales or concession stands than serving as a coach. Parents with children in baseball and basketball are far more likely to serve as volunteer coaches than other sports.

The lack of volunteer parent coaches could be the result of more paid coaches as the youth sports industry has become more privatized. Also, sports organizations face significant challenges to find anyone to coach, whether paid or volunteer. Separate research from the Sports & Fitness Industry Association shows the number of current coaches decreased by 1.2 million from 2022 to 2024 after a major spike coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Source: Sports & Fitness Industry Association

Urbanicity, race and socioeconomic status influence volunteer patterns. In the latest Aspen parent survey, rural parents (45%) and suburban parents (43%) reported volunteering at higher rates than urban parents (32%). However, across almost every volunteer category, parents in urban communities volunteer at higher rates than those from suburban and rural communities. Urban parents also spend more hours volunteering than others.

Parents of Black and Hispanic children volunteer at higher rates and for more hours than parents of White children. And parents from households making $100,000+ volunteer at higher rates (66%) than those from households making under $50,000 (57%).

“It takes a village to run a youth sports program, and parents are typically the labor force, often contributing many hours a week without compensation,” Dorsch said. “And the number of tasks that need to be completed has increased exponentially with the proliferation of travel teams and leagues.”

Volunteering as a coach, referee or supervisors of sports teams accounted for about 9% of all volunteer activities in the U.S. as of 2015, according to data by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That ranked fourth behind fundraising, food distribution and tutoring.

Family eating habits are affected by sports

The rush to chauffeur children to sports can mean a lot of eating on the fly. More than half of youth sports parents (56%) say they eat out for two to four meals per week due to their child’s sports schedule, according to the latest Aspen survey.

Slightly more than 1 in 10 families eat out five to seven meals per week due to sports. Three in 10 families eat none or one meal out per week. Urban parents, parents of minority children and parents from more affluent households report eating out the most while juggling their child’s sports schedule.

A significant portion of surveyed parents (36%) believe that their family's commitment to youth sports contributes to unhealthy eating habits. The wealthiest families are more likely to say this is the case.

Is this the right sports model for families?

As parenting behaviors have changed broadly over several decades, so too have the roles and demands on parents in sports, which have become a highly commercialized and privatized industry. Expectations of what it means to be a sports parent have changed.

Research by Ohio State University found that parents today are spending more time on their child’s sports than previous generations. Adults born in the 1950s said their parents attended their sports events only a few times a year. But adults born in the 1990s said parents with a college degree came to their games about once a week while parents with lower levels of education came about once a month. The study essentially covered youth sports experiences from the 1960s through about 2015.

“Our findings suggest that recent changes in youth sport and parenting cultures have prompted parents to invest more time and money in their children’s athletic activities,” said Chris Knoester, lead author of the student and professor of sociology at Ohio State. “Since the 1980s, supporting a child’s athletic development has appeared to have required levels – or at least felt pressures – of involvement not demanded of parents in previous generations.”

Research by the Harris Poll showed almost 8 in 10 parents today support reducing travel for sports, while 72% want a model with fewer games and more practice. Nearly the same percentage of parents (73%) say youth sports have lost sight of their original purpose – fostering fun and teaching teamwork.

“The status quo is serving a select few who could one day become WNBA All-Stars or major championship winners in golf,” wrote The Harris Poll CEO Will Harris. “But what about the rest of America’s sports families? The system may not be broken for the few, but it’s looking more and more so for most.”

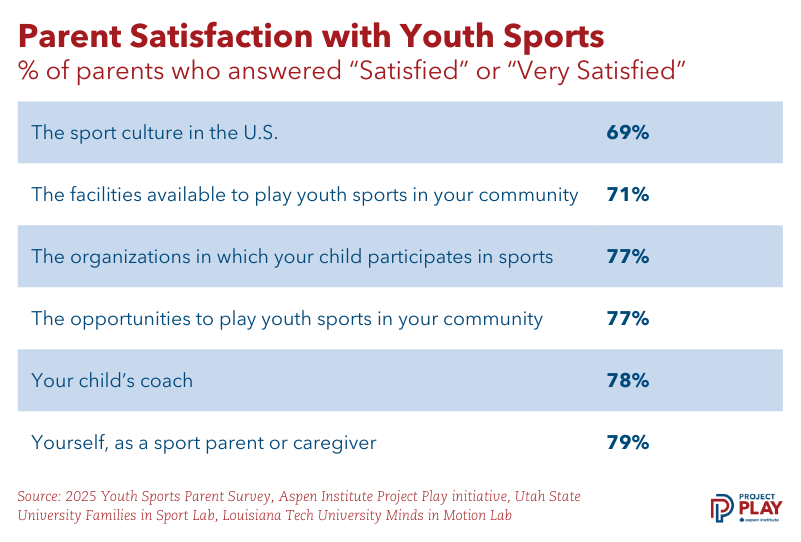

In our Aspen survey, 69% of youth sports parents reported being satisfied with the sport culture in the U.S. Generally, parents rated individuals and entities progressively worse the more distant they were to their family.

And yet it’s still a major time commitment. For an average of 3 hours and 23 minutes each sports day, parents are tied to their child’s sports experience.

That number uncovers the extent of modern parents’ anxiety over their children’s futures, illustrating how tightly tethered parents are to their children’s lives that they would give up their own adult relationships, leisure and health along the way, Flanagan said.

“At the same time, if the typical sports parent devotes 20 hours a week to his or her child’s athletic development, coaches and leagues should expect lots of parent interference in the way things are done,” Flanagan said. “Squabbling over playing time, strategies, positions and other coaching decisions are the natural outgrowth of parents’ outsized devotion to their kids’ sports.”

Developing tools and strategies to better serve parents is a focus this year of 63X30, a roundtable of 20 leading organizations in the sport, health and tech sectors that the Aspen Institute has convened to help get 63% of youth playing sports by 2030. This survey was funded with support from the initiative, various members have introduced new campaigns or programs, and Aspen recently released Project Play Parent Checklists – 10 questions that parents can ask themselves, their child and their local sport provider to get and keep their child in the game.

“Parents will do just about anything for their child to keep them involved in sports,” said Tom Farrey, executive director of the Aspen Institute's Sports & Society Program. “That’s why they give themselves high marks for supporting their child – because it’s a lot. We hope the results of this survey cause sport providers to build new models that aren’t so taxing on parents’ time or wallet. At some point, there’s just not more time in the day to give or funds to expend.”

Jon Solomon is Community Impact Director of the Aspen Institute Sports & Society Program. Email him at jon.solomon@aspeninstitute.org.

Survey Methodology

The Aspen Institute’s National Youth Sports Parent Survey, in partnership with Utah State University and Louisiana Tech University, utilized a nationally representative survey of 1,848 youth sports parents whose children participate regularly in one or more sports activities. The survey was conducted online in November and December 2024 with parents of children ages 6-18 from every state and the District of Columbia. The research sought to address patterns of youth sports participation, parents’ involvement in that participation, and the characteristics of the settings in which participation occurs. Read the full survey results. The Aspen Institute will publish additional analysis of the results throughout 2025.