Photo: Getty Images

The Aspen Institute’s Project Play initiative partnered with Utah State University and Louisiana Tech University to survey youth sports parents, releasing in March 2025 with a 148-page report that helped inform several sessions at Project Play Summit 2025. Now, we’re analyzing key findings in depth. This sixth story in our year-long series examines the sports experiences of parents of children with disabilities.

Fourteen-year-old Andrew once felt invisible on the playground, the only child in a wheelchair, left behind and battling depression as he struggled to accept his new reality. But when his family moved from the East Coast to Portland, Oregon, for better medical care and access to adaptive sports, everything began to change for Andrew.

“My son was really frustrated in elementary school when he was the only child in a wheelchair,” said Andrew’s mom. “Kids would leave him behind and they didn’t understand him, so he was really wanting to have wheelchair friends. He’s had depression since he was injured as a child and thought he would become all the way better. He didn’t really accept that this is his reality and he needed to find a way to grow into his current ability and body to feel great about himself. It’s pretty tremendous to get him in sports.”

Now in his second season of wheelchair racing — with rock climbing, kayaking, and even rugby on the horizon — Andrew (not his real name for privacy reasons) has found not just competition, but community, confidence and the chance to be seen as an athlete.

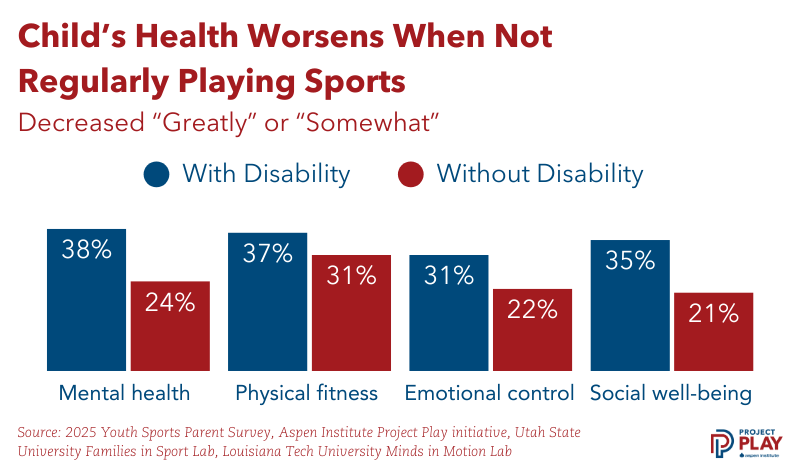

Andrew’s challenges are not uncommon. Disabilities often prevent access to sports. Even among children who play, those with disabilities annually participate almost one month less in practices or competitions than their peers without disabilities. The lack of play can be impactful – parents of children with disabilities are more likely to believe their child’s health worsened when not regularly playing sports.

The findings are among the latest results analyzed by the Aspen Institute’s youth sports parent survey in partnership with Utah State and Louisiana Tech University. In the survey, 23% of respondents indicated their child has a documented disability, such as a physical or intellectual disability, autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, vision, hearing, learning, chronic disease or other disabilities.

Figure 1. Child’s Health Worsens When Not Regularly Playing Sports. See notes for descriptive text.

Our survey’s key findings:

On average, children with disabilities who participate in sports play about five months during the year compared to 5.7 months for those without disabilities. The survey only accounted for parents with a child currently playing sports, not those whose children don’t participate at all.

For the most part, children with and without disabilities who participate enjoy similar sports. Basketball, baseball, soccer, tackle football and dance are the most-played activities. The data may be similar because many of the survey respondents had children with mild or cognitive disabilities who may play in mainstream sports rather than children with physical disabilities.

Safety is more important for parents of children with disabilities. They ranked abuse prevention training for coaches as more important than parents without a disabled child.

Sports parents of children both with and without disabilities show almost no difference regarding athletic aspirations for their child. For instance, they believe their child can reach the Paralympics (10%) or Olympics (11%).

In 2022-23, 47% of children with special health care needs played organized sports at least once in the previous year vs. 58% of kids without special health care needs, according to separate data collected by the National Survey of Children’s Health.

Figure 2. Top 5 States for Children with Special Health Care Needs. See notes for descriptive text.

Figure 3. Bottom 5 States for Children with Special Health Care Needs. See notes for descriptive text.

Traditional school and club-based sports often lack the resources to effectively include children with disabilities, leaving families reliant on nonprofit organizations to fill the void, said Julia Ray, programs director at Move United, which offers more than 70 different adaptive sports.

“This creates an unnecessary barrier when solutions are readily available,” Ray said. “Sport providers – whether community-led programs, after-school initiatives, or individual coaches – can embrace current inclusion best practices and available resources. A coach is fundamentally someone who adapts instruction to meet athletes’ varying skills and motivations. Athletes with disabilities are no different. We need a fundamental shift in mindset to create meaningful change, similar to what Title IX accomplished for women’s and girls’ sports.”

Photo: Getty Images

Isolation is a critical concern

More than 3 million children in the U.S. have a disability, representing 4% of the population under the age of 18. Yet while 15% of public school students receive special education services, less than 1% participate in adaptive sports programs or Unified programs at schools, even as high school sports participation grew to 8.3 million participants in 2024-25.

Efforts have been made by policymakers to address such deficits, with mixed results. The American Disabilities Act of 1973 requires schools and community programs to give students with disabilities an equal chance to participate in sports. In 2013, the U.S. Department of Education wrote a clarifying Dear Colleague letter that offered guidance for schools:

Don’t make assumptions or stereotypes about disabilities. Schools must evaluate students individually and apply the same criteria to everyone.

Make reasonable modifications to policies and procedures so students with disabilities have equal opportunities to sports. Provide necessary aids and services unless doing so would fundamentally alter the athletic activity.

Strongly consider creating sports opportunities for disabled students who play in existing programs. This could include disability-specific teams such as wheelchair basketball, and consider developing a district-wide team to have enough students.

“We’ll never know if the letter was impactful because there weren’t any measurements or metrics built into the letter,” said Dawna Callahan, CEO of All in Sport Consulting, which helps advance adapted sports. “As a person with a disability, it very much seemed like a nice, friendly reminder, ‘Hey, don’t forget there’s these disabled students you need to support too.’ I don’t think it’s had much impact because I still hear about the same issues today as I did back in 2013. If there has been an impact, I think it has to do with general awareness and exposure, not necessarily due to the letter.”

The 2013 “Dear Colleague” letter has been cited in legal cases and public commentary. However, courts generally treat these letters as guidance rather than binding law. Plaintiffs still must prevail under controlling statutes. Several state high school athletic associations have settled lawsuits over issues addressed in the “Dear Colleague” letter.

The result of no sports can be consequential for all children. But the Aspen survey notably shows parents of children with disabilities witness worse mental health, physical fitness, emotional control and social well-being when their child did not regularly play sports.

“Isolation is a critical concern for youth with disabilities,” Callahan said. “This stat really highlights the importance of sport for those with disabilities. It not only helps with their fitness, but is also important for social well-being and mental health. Sport may be their community and connection, so if the sport opportunities decrease, the various stressors increase.”

From Project Play Summit 2025: Youth with disabilities often face the greatest barriers to sport participation. We unpack the challenges for the populations falling within this category, with an eye toward solutions that can be scaled.

The difference for months spent in sports aligns with other research showing that programming for children with disabilities often occurs in school sports through partnerships with national and state associations.

“Unlike programming that is non-school related that can be offered year-round, the school-partnered programming is limited to the school’s calendar,” said Dr. Andrew Parks, assistant professor of kinesiology at Louisiana Tech University. “These partnerships differ from school-sponsored activities as they are not authorized and run by the school itself, but are arranged to be run by the external organization with the schools’ support.”

For the most part, children with and without disabilities who participate enjoy similar sports. Basketball, baseball, soccer, tackle football and dance are the most-played activities.

Figure 4. Top Primary Sports Played by Children With Disabilities. See notes for descriptive text.

Figure 5. Top Primary Sports Played by Children Without Disabilities. See notes for descriptive text.

Parents of children with a disability reported feeling more pressure from their child and other parents to encourage their child to specialize in their main sport. “While this is a factor for both populations, children with a disability and their parents may perceive this as a greater pressure due to the even more limited opportunities for positions in these sports the higher the competition level gets,” Parks said.

Parents of children with disabilities ranked abuse prevention training for coaches as more important than those without a disabled child. That’s in line with separate research showing that athletes with physical or intellectual impairment are up to four times more likely to be victimized than athletes without impairment.

In Aspen’s survey, almost one in four parents of children with disabilities (24%) indicated their child has faced inappropriate pressure or exploitation in sports. The rate was 19% for parents of children without a disability. Parks said children with impairment can feel heightened vulnerability, fear retaliation and believability, and impaired ability to protect oneself.

“Coaches are the most common perpetrator of this and often lack training for how to effectively support children with disabilities,” he said. “As a result, this can present an added challenge for parents of a child with a disability to navigate the process of thoroughly vetting a program and coaches prior to their child participating.”

Photo: Getty Images

Providers struggle with promotion

What the Aspen parent survey doesn’t show is the large number of children with disabilities who have never accessed sports at all. The survey only accounts for those kids already playing sports; many others are sitting out.

Four in 10 individuals with disabilities that do not play sports want to play sports, and 7 in 10 individuals with disabilities are not aware of organizations that can support them, according to Lakeshore Foundation in Birmingham, Alabama. Children with disabilities need more opportunities to learn about physical health literacy, how their body moves and what they are good at and enjoy physically, said Amy Rauworth, chief research and innovation officer at Lakeshore Foundation.

“Yet too many of these opportunities are still not accessible to youth with disabilities,” she said. “The playground is not accessible, the afterschool program does not have the staffing or programmatic knowledge to be inclusive, and it is left up to the parent to prioritize their child being physically active, and they already have a long list of things to address.”

For sports providers who serve children with physical disabilities, the biggest challenge is getting the word out to parents that programs exist for their child to play.

“Parents don’t believe their kid can play basketball because they’re in a wheelchair,” said Stan Weston, president of Kansas City-based Midwest Adaptive Sports. “I tell them, ‘Bring them out. Let us show you.’ Parents don’t understand that their kids can do it.”

In some communities, disabled children have no choice but to travel in order to play sports, both locally for practices and regionally for games. In Kansas City, a bi-state metropolitan area with over 2.2 million people spanning 14 counties, only one wheelchair basketball team exists for each age group. With no one to play locally, families must travel to cities like Wichita, St. Louis, Omaha and Minneapolis for weekend tournaments.

“You’ve got all those expenses taking your family on a three-day vacation about six times a summer, and that’s a real drawback,” Weston said. “We try to have fundraisers, grants and donations to help out with that, but you don’t get it all covered.”

When the Aspen Institute held focus groups in Portland, Oregon, with disabled youth and their parents, they spoke of the need to educate all students about the challenges faced by children with disabilities and for schools and sports providers to take proactive measures.

“Schools often react to needs once you tell them rather than proactively creating inclusive sports programs,” said one mom. “That leads to a lack of options for children with disabilities because a lot of parents and children don’t speak up or know what’s possible.”

In Aspen’s survey, the settings where disabled children play sports were relatively similar to all children. Parents of disabled children reported slightly more engagement in free play, community-based sports, and intramural settings and slightly less engagement in interscholastic, travel/elite or club and independent training settings.

Figure 6. Setting Where Children Regularly Play their Primary Sport. See notes for descriptive text.

“While the American with Disabilities Act ensures an inclusive environment for all youth to engage in sports programming, there is often a lack of training and understanding how to best include these individuals and serve them,” Parks said. “In community-based programs, free play or intramural, the adaptations to rules, equipment and strategies are more readily applied. Adaptation is more challenging at the interscholastic, travel, elite or club level due to the competition level of the program.”

Callahan, a national expert on disabled sports, said Aspen’s findings showing differences in travel sports participation reflect the most important gap in the U.S. Paralympic athlete development pipeline. “If this figure was higher for youth with physical disabilities, it would show up in a more robust U.S. Paralympic pipeline,” she said.

Interestingly, sports parents of children both with and without disabilities express similar aspirations for how far their child can take organized sports.

Figure 7. Highest level of sports parents believe their child can reach, by the child's disability status. See notes for descriptive text.

Parents believe in their children, no matter if they have a disability or not. Whether that narrative happens more often throughout society remains to be seen.

“This non-difference across all levels is intriguing as it does not fit the common misperceptions of ability for children with disabilities,” Parks said. “Instead, it more accurately fits the research models of physical activity, motor development and sport participation that most children with disabilities are highly capable of engaging in physical activity and sport. Opportunity is often the greatest limiting factor.”

Youth with disabilities, such as this child with a cochlear implant, face unique barriers to participation. Photo: Getty Images.

Jon Solomon is Community Impact Director of the Aspen Institute Sports & Society Program. Email him at jon.solomon@aspeninstitute.org.

Survey Methodology

The Aspen Institute’s National Youth Sports Parent Survey, in partnership with Utah State University and Louisiana Tech University, utilized a nationally representative survey of 1,848 youth sports parents whose children participate regularly in one or more sports activities. Of those surveyed, 426 people (23%) identified they have a child with a documented disability. Parents in the survey documented intellectual (66%), physical (8%), sensory (7%) and multiple disabilities (19%). The survey was conducted online in November and December 2024 with parents of children ages 6-18 from every state and the District of Columbia. The research sought to address patterns of youth sports participation, parents’ involvement in that participation, and the characteristics of the settings in which participation occurs. Read the full survey results comparing sports parents of children with disabilities to all sports parents. The Aspen Institute will publish additional analysis of the full parent results throughout 2025.