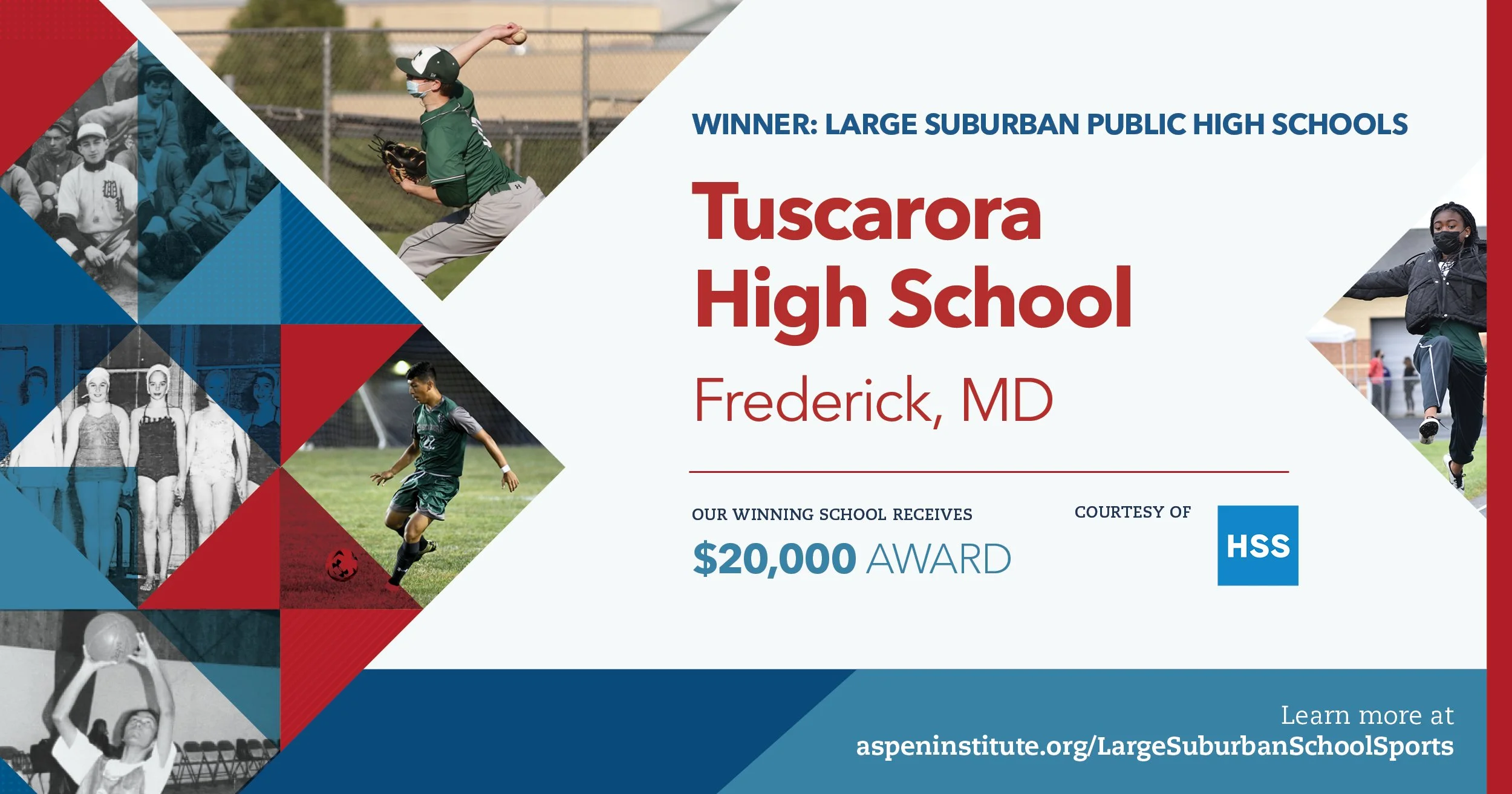

Large Suburban winner:

Tuscarora High School

Frederick, Maryland

As a freshman, Jackson VanTassell was ready to transfer from Tuscarora High School to a private school. He had his baseball career mapped out – travel ball tournaments up and down the East Coast, high school success and then college baseball. His plan did not account for a struggling baseball team at Tuscarora.

When a PE teacher was hired as the new baseball coach, VanTassell decided to stay. He’s thankful he did, given friends he made at Tuscarora from so many different backgrounds, whether through his role coaching special-needs students in sports, playing with less-talented classmates in physical education class and intramurals, or building lasting relationships with his PE teachers.

“Tuscarora’s diversity made me into the person I am today,” says VanTassell, a senior who will play baseball at Radford University starting in 2021. “I will never judge anyone by what they look like because of what I learned here. Playing with all kids at PE and intramurals is a big part of that.”

Tuscarora High School, located in Frederick, Maryland, embraces physical activity during school hours as a co-curricular asset tied to education. Intramural volleyball and basketball activities, plus table tennis, badminton and strength training clubs, are periodically available during daily flex periods. Unified sports teams in tennis, bocce and track and field allow Tuscarora students with disabilities and general education students to play and learn together.

These efforts are led by a group of PE teachers who students say possess a unique ability to relate to them in ways very few teachers can. For its ability to find joy, relief and meaning through physical activity during the school day, Tuscarora is recognized as the Aspen Institute’s Project Play winner in the Large Suburban Schools category of our Reimagining School Sports initiative.

“Somehow along the way we lost the notion that kids in high school don’t want to play or be physically active, and that’s not accurate,” Tuscarora Principal Christopher Berry says.

Too often, Berry says, high schools incorrectly assume that interscholastic sports teams meet the needs of students to be active, when in reality many students arrive in high school without a competitive sports background and thus won’t make their team. “This leaves kids with this belief that sports are not for me, and therefore exercise in school is not for me, and that’s too bad,” he says.

Parents also play a role in creating this misperception by believing every activity must have a purpose and firm structure, Berry says. “What you’re doing by offering an extension of PE class is giving kids an opportunity to just have fun,” he says. “It doesn’t have to be something you put on a resume. Learn something new and hang out with your friends in a way that allows you to burn off some energy, and maybe you’re more focused in class.”

Research shows physically active children score up to 40% higher on test scores and are 15% more likely to attend college. Nationally, 68% of suburban high school students report they enjoy PE class and 13% say they dislike it, according to a survey by the Aspen Institute. Another 14% have never taken high school PE.

At Tuscarora, a school of 1,600 students, the only required PE section is a health and fitness course. But before the pandemic, students regularly signed up for more than one course. Usually, about one-third of the students takes PE at any given time, says Howie Putterman, the school’s athletic director and a PE teacher.

In 2019-20, 1,108 Tuscarora students enrolled in PE, taking 90-minute courses like health and fitness (414 students), strength training (275), team sports (90), basketball (80), sports medicine (63), volleyball (60), soccer (40), coaching (23) and Unified (15). In addition, school officials estimate about 300 students participated in intramurals or clubs involving physical activity, many of which are led by PE teachers Mike O’Brien, Dean Swink, Mark Angleberger, Jess Valentine and Putterman.

“PE is popular with students because of the teachers,” VanTassell says. “They’re the most personable people in the building by far and they’re always willing to go the extra mile for you. They’re so interested in your success and not their own agenda. It’s such a healthy relationship with all of them.”

Rachel Nichols, a senior lacrosse player, enjoys talking with O’Brien (or Coach OB, as he’s called) about how to be a leader and handle problems within her team. It doesn’t matter that O’Brien isn’t her coach. “They all really understand where you’re coming from,” Nichols says.

When a Tuscarora student died a couple years ago, senior Mallory Brown remembers Swink was the first person to comfort her and calm her down. “Anything you ever need to talk about, the PE teachers are the people everybody goes to,” Brown says. “I think of them like family.”

Many times, the conversations between students and PE teachers dive into difficult issues. Politics, college choices, financial trouble at home, sexual orientation, and boyfriend/girlfriend trouble get discussed.

“That probing, that interest in what’s on the kids’ mind, is what draws the kids to the PE teachers,” says Putterman, noting that more Tuscarora students ask to be classroom helpers in PE than any other subject. “Kids’ lives are controlled for seven hours a day. We still have a curriculum, rules and things we have to do in PE. But they’re dying to be adults, and we give them some freedom and the ability to have adult conversations.”

Sometimes, conversations between Tuscarora PE teachers and students lead to new intramural sports or clubs. The strength training club started after a student asked a PE teacher to lift at school since he lacked access to a gym. That became a club with 20-50 students working out each day, many of them non-athletes.

In the pre-COVID era, intramurals were very popular during flex period, a county-wide time designed for students to receive tutoring, make up schoolwork and participate in clubs. It’s a 35-minute daily window, usually from 10:35-11:10 am, that the Tuscarora PE department turned into an opportunity for physical activity.

There have been seven-week volleyball tournaments in which students selected teams based on class (two teams each for the freshman, sophomore, junior and senior classes). Two or three games were played each flex period. The final four teams played at the winter pep rally, with the winning student team advancing to play a staff team in front of the whole school.

Each March, Tuscarora usually holds a three-on-three intramural basketball tournament during flex period. There’s an NBA division for advanced players and an NCAA division for less-skilled students playing for fun. Badminton and table tennis clubs plus flag football powderpuff preparation have also occurred during flex period. If anything, some students say they wish Tuscarora had more intramurals, such as capture the flag, handball, dodgeball and cornhole.

The school’s English Language Learners use physical activity during the day to recharge their minds. They often visit the gym once a week to play soccer. Learning for Life, a structured classroom for students with developmental and cognitive disabilities, also regularly takes its students to shoot baskets, play hockey or just go for a walk in the gym.

“My best friend is my bocce partner since freshman year,” says Brown, a senior. “She has Down syndrome. Everybody gets to benefit from playing Unified sports.”

Tuscarora, located about one hour northwest of Washington D.C. and Baltimore, in some ways represents how suburban schools are evolving. The days of suburban schools being predominantly White are changing. Although Frederick County, where the school is located, is 81% White, only 41% of Tuscarora’s students are White. Tuscarora pulls from inner-city Frederick with gang violence, rural communities with farms, and affluent families with single-family homes.

“There are students on public assistance and students living in million-dollar homes,” says Berry, the principal. “As an educator, you have to really understand who the kids are in front of you because there’s not a typical Tuscarora kid.”

PE can be a safe haven. Some students with behavioral issues in academic classes excel in PE – and later boost grades in other classes – because it’s an opportunity to let loose and gain confidence, O’Brien says.

Some students want nothing to do with PE, so O’Brien keeps those conversations positive and the goals attainable. He doesn’t require those students to change into gym clothes, which can be a barrier to participate. He tells those students just try the activity today to see if they like it, and tomorrow they can try something else.

“We have kids used to middle school where you have to change and play basketball for three to four weeks,” O’Brien says. “We can find something that’s a little niche and it develops into something they didn’t realize they would like. It’s all about talking to a student, because there are kids who don’t hear anything positive throughout a school day, and that positive comment can light a spark.”

Putterman is concerned about Tuscarora’s immediate future with PE. Not surprisingly, enrollment in PE plummeted during COVID as the school went remote and then reopened. “Hybrid PE is unfortunately a joke,” Putterman says. “No one signed up for PE to write papers on researching the Premier League. That’s work, not play. We teach you things through PE, but it’s through play.”

The PE department lost two sections of strength training and one section each on volleyball, soccer, and coaching (a class in which students learn coaching philosophies and financial budgets and also coach classmates during intramurals). Because fewer students registered for PE in 2021-22, Tuscarora lost the equivalent of half a PE teacher, dropping to five-and-a-half positions among six staff members. The 2021-22 student PE enrollment numbers will probably be the lowest since Tuscarora opened in 2003, a concern of school officials who know they will inherit more mental health challenges due to the pandemic.

“Half of the school won’t know us,” Putterman says. “I think kids haven’t signed up for PE because they didn’t get to know our teachers. They’re just not drawn to come down to us at any moment like they used to be.”

Sometimes students find their way back to PE. Nichols, a highly competitive senior lacrosse player, says she had no time for PE as a sophomore and junior due to college-level classes and club lacrosse during pivotal recruiting years.

Then Nichols got appendicitis that knocked her out of club tournaments. Then COVID hit. Suddenly, she had not committed to a college yet by the summer before her senior year. “All of that led to massive burnout (on sports),” says Nichols, who will play lacrosse at Frostburg State University. “Burnout is for real.”

As a senior, she took a PE strength training class. “It was my chance to be active and just decompress.”

Often, that’s all students need from physical activity during school hours – a chance to breathe.

Strategies that Tuscarora High School uses that stood out as exemplary to the Aspen Institute and our project advisory board:

Let kids shadow high school athletes

To grow fan attendance and encourage younger children to play sports, Tuscarora allows students in grade school to occasionally shadow varsity players before a game. The child experiences the pre-game meal, player warmups and the coach’s speech. Athletic Director Howie Putterman says the event works especially well for girls’ teams. “For a 10-year-old girl to go into a team room, that’s like you or I walking into Ravens Stadium,” he says.

“Create “Free Play Friday” in PE”

On Fridays at Tuscarora, every PE section mixes together so students participate in whatever sport or activity they want. Some play basketball, volleyball, badminton or soccer. Some toss a football. Some lift weights or do cardio exercises. Some fast walk around the gym. Some dance to Just Dance videos on the TV. The point: Students, not adults, choose what they want to play.

Use team practices to promote academics

One in three Tuscarora students are academically ineligible, often due to lack of educational support at home, trauma in their life, or periods of interrupted education. Ineligible students cannot play games or travel with their team, but unlike the policy of a neighboring county, they can still practice. “At first I wasn’t sure I liked this policy,” Putterman says, “but it’s a huge carrot and it keeps some kids engaged.”