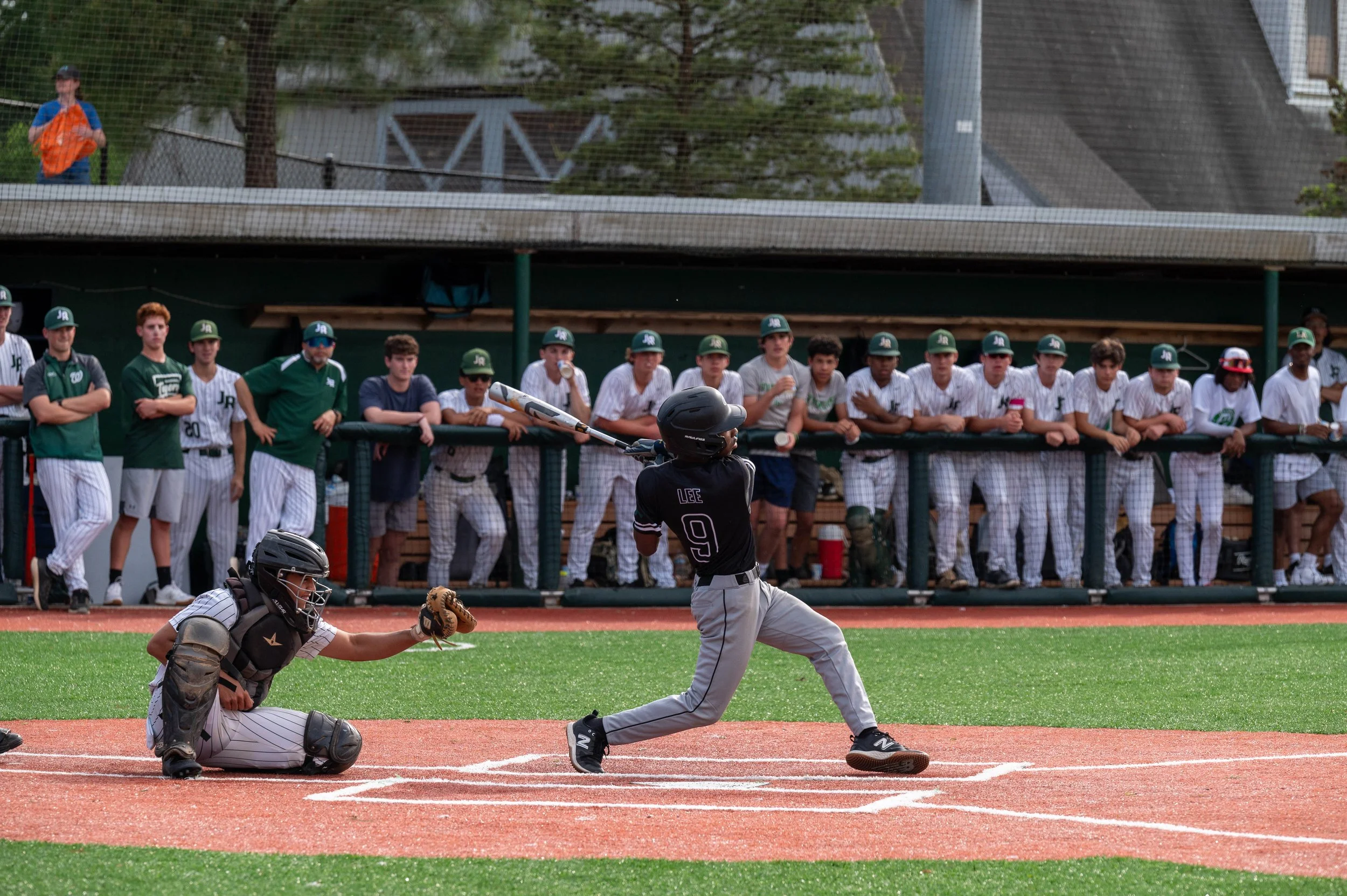

Photo: DCIAA

The following article was originally published in the Aspen Institute’s State of Play Washington D.C. report. The report assesses the opportunities and barriers for more children to access sports and physical activity in our nation’s capital.

Washington D.C. is filled with many quality and well-intentioned sports providers, coaches and government and school officials who want to make a difference in the lives of children. They just often operate in silos and without a cohesive vision to leverage assets and help grow quality access to sports for all children.

Youth sports are a messy, siloed space. Club and school coaches don’t communicate well with each other. Programs fight for facilities space and get frustrated with maintenance. Efforts to reach underserved populations are scattershot.

Although rarely enough, some valuable investments in youth sports are being made in the District. Examples include grantmaking, pro sports investments, new facilities, expanded middle school sports programming, robust elementary school sports offerings, and collaboration by nonprofits. (Go to as.pn/DCInvestments for a list of some valuable investments made in the District in recent years.)

What’s missing is a more coherent system that creates a long-term pathway for more District children to engage in sports and physical activity. How can these various entities leverage their knowledge and resources to create quality, affordable local opportunities for children to play at every age through programming that’s welcoming and fun?

Like many communities, D.C. lacks a shared vision for what a youth-centered sports ecosystem looks like and why we want children to play. Is the goal simply to create more college and professional athletes? That has value, within reason. But most young people who play sports quit well before then, having been weeded out at young ages due to costs and ability.

During focus groups with many District children, we heard common themes about why they play sports — to be with friends, to find joy, to distract from problems, and to identify a positive pathway in life away from violence. Some young people said they lack parental support to access sports, meaning it’s up to the child to find a way to play.

“If I hadn’t played sports, I probably wouldn’t behere,” said a 19-year-old male now attending the University of the District of Columbia. “If you don’t play sports, there are a lot of bad things you could do. My parents didn’t really care. In my 11th grade year, I started playing to save myself.”

Research shows that when high schools have strong sports participation rates, they report lower levels of major crime and fewer suspensions. Other studies find physically active children receive more physical, social, emotional and academic benefits, including being less likely to skip school. (Learn more about the impact sports can have on absenteeism in D.C. schools at as.pn/DCAbsenteeism.)

To be clear, playing sports doesn’t in and of itself result in these benefits. While sports can help personally develop young people, the opposite can be true too. If sports are not a youth centered experience, they can damage a child’s mental health or cause children to quit.

D.C.’s sports participation rate is 62% — above the national average, according to 2022 and 2023 data from the National Survey of Children’s Health. D.C. is nearing the goal of 63% by 2030 set by the federal government and championed by Project Play. But dig deeper and there are tremendous disparities by gender and race, often due to costs, transportation and some sports environments that are not as welcoming as they could be.

Solution: Create a D.C. Athletic Council to connect silos

Across the DMV region, local governments are paying closer attention to how sports in their areas are organized and made available to youth. Fairfax County, Virginia, and Montgomery County, Maryland, are leaders in this effort, forming advisory groups in which community representatives regularly meet to balance competing interests and address issues ranging from field permits to facility rental prices to programming costs.

These issues, and more, can be found in the District of Columbia as well. We recommend the D.C. government support the creation of its own advisory group, drawing on the templates created by other communities and adapting as appropriate, in consultation with citizens and stakeholders, to determine the mission, scope and representation. The group could sit inside or outside the government and would have governmental support either way.

Athletic Council members could include representatives from the most popular sports, as well as District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS), Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR), District of Columbia State Athletic Association (DCSAA), the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Education (DME), and the Office of Out of School Time Grants and Youth Outcomes (OST Office). Other members could include representatives from pro sports teams, businesses, public entities and community sports providers. Fight For Children, a collaborative network of nonprofits using the power of sports to improve the lives of children, would be an essential member of the council and could serve as its convener.

The council could target its collective and individual efforts by aiming for 63% participation by all subgroups of children tracked in the research who are playing sports at lower rates, such as girls, Black children and those with special needs.

Thennie Freeman, director of DPR, signaled support for a more coordinated approach to sports during public testimony on permitting in 2024. “I would like to see a unified system,” she said “One thing Mayor (Muriel) Bowser spoke about is how do families know what the access points are for sports? Where would one hear about these organizations and activities unless you’re already in that particular circle?”

Another option is the city government could endorse or financially support a non-government entity that serves as a coalition of stakeholder groups with the responsibility to increase youth sports opportunities in partnership with government agencies. This model, too, has been effective in some cities.

The city of Philadelphia financially supports the Philadelphia Youth Sports Collaborative (PYSC), a coalition of grassroots organizations that acts as an intermediary between the city and everyone else. The city allocated $3 million in 2025 to a youth sports agenda. PYSC has received more than $1 million through contracted work with the parks and recreation department and another $525,000 from the city to distribute grants to small, neighborhood-based nonprofits.

No matter how silos across the District get connected, members of the “State of Play Washington D.C.” advisory group see value in creating a venue to continue to develop shared solutions to common problems. Many advisory group members who helped guide this research found the collaboration invigorating. They came from city government, schools, parks and rec, police, nonprofits, pro sports teams and more — a rare opportunity for these leaders to learn from each other and find opportunities for collaboration.

Initiatives by the council

Building long-term collaboration will not happen overnight. The “State of Play Washington D.C.” advisory group is committed to continue meeting and determine how to create a sustainable council, which would require public and/or private funding for multiple years to succeed.

The council could address high-impact areas outlined in this report, with a strong focus on reducing barriers for girls and children of color to access quality sports opportunities. Other areas of focus could include training more coaches and creatively improving sports providers’ access to and quality of public facilities.

The council could focus on short-term, medium-term and long-term projects while celebrating wins as they happen. Wins build momentum.

Short-term examples

Provide more training and mentorship opportunities for coaches. There is a need for sustained development of coaches at all ages around positive youth development — and more than just one-time trainings.

Create a master list of sports facilities and fields in the District and who permits them. Compile them into one central location, like a website, for sports providers to visit and learn how to access play spaces run by various D.C. entities (schools, DPR, Events DC and National Park Service).

Develop more after-school partnerships between OST and community sports providers. OST supports the equitable distribution of high-quality, out-of-school time programs to D.C. youth through coordination among government agencies, grant-making, data collection and evaluation, and technical assistance to service providers. These service providers, who largely don’t offer sports, figured out the bureaucracy to get their programs into public schools. The goal is to help more sports providers learn how to partner with OST and encourage some OST non-sports providers of the benefits to add a sports component to their work.

Medium-term examples

Build an online youth sports directory. Help families identify the right league, team and pathway for their children. Use data collected from sports providers to identify systemic challenges in D.C. and build sustainable solutions.

Provide sustained investment in programming for underserved populations. Members of the council could advocate for greater public funding for sports opportunities. This could include expanding the city’s $1 million annual allocation to Events DC for grantmaking of youth extracurricular activities, including sports.

Align pro team investments around girls sports. The audience for women’s sports is booming, but far too few girls in the District play. The Washington Mystics (WNBA) and Washington Spirit (NWSL) are focused on growing girls’ participation. Other D.C. teams could join them to invest in multisport programs for girls, education and distribution of sports bras, and initiatives to attract more women into coaching.

Long-term examples

Public awareness campaign on the value of sports. It’s not enough to hope the public understands how sports can help keep children safe, improve their academics, and boost their physical, emotional and social health. Attention spans are short and the public focus on sports often centers on game results. With a media partner, the council could collaborate on a campaign to educate D.C. residents about the value of sports participation that also attracts sports investments from public and private sources.

Recruit college athletes as youth coaches. There are 22 colleges and universities in Washington D.C. With youth coaches hard to find, the council could recruit and train college students to coach children for university credit and/or stipends.

Create one comprehensive permitting system for facilities. Fields are incredibly scarce in D.C. Currently, DCPS and DPR share permitting software, but every entity that operates public fields (such as DCPS, DPR, Events DC, and the National Park Service) has different rules and guidelines. This can be confusing and inefficient for the public. While it would be challenging for agencies to give up authority given their own needs for facilities, the council could work toward the goal of creating a more functional system.

Collaboration is never easy. It requires give and take, along with investments of time, money, trust and energy — all of which are in short supply. But the payoff of such an entity in D.C. could be significant, even by starting small as a knowledge-sharing group with smart, thoughtful leaders who want to collaborate, learn from one another and help all D.C. children.

Athletic Council Model in the DMV Region

Fairfax Co., Virginia

Since the 1970s, the Fairfax County Athletic Council has served in an advisory capacity to the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors, the school district board and county agencies on sports-related matters. Why the 23-member council is effective:

Representation exists across districts, sports, and government bodies.

Historical knowledge of the county’s residents, programs, facilities and systems ensures thoughtful and knowledgeable insight, which confers legitimacy.

Manageable size allows the flexibility to act.

Includes sports representatives close to the ground with authorities from essential governing bodies (park authority, school district, county government).

Appointed representatives are respected among their constituents and have a longstanding interest in sports.

The Board of Supervisors continues to support the council.

Montgomery Co., Maryland

Concerned about inequities in access to sports during COVID, the Montgomery County Council in 2022 established its Sports Advisory Committee to make more effective use of county resources. Why the 17-member committee is effective:

Diverse group of members are united in their desire to improve the quality and availability of programs.

Montgomery County Council is fully supportive.

Each of the county’s seven districts are represented.

Committee appointments follow the standard county process for selecting and confirming appointments.

The committee has a “let’s-get-stuff-done” approach to the work.

It’s a standing committee with staggered three-year terms, which creates continuity and fosters institutional knowledge.

Jon Solomon is Community Impact Director of the Aspen Institute’s Project Play initiative. Jon can be reached at jon.solomon@aspeninstitute.org.