Tom Farrey speaks at “Benched: The Crisis in American Youth Sports and Its Cost to Our Future,” December 16, 2025. Photo: House Subcommittee on Early Childhood, Elementary, and Secondary Education.

Tom Farrey submitted the following written testimony to the House Subcommittee on Early Childhood, Elementary, and Secondary Education for the hearing “Benched: The Crisis in American Youth Sports and Its Cost to Our Future” on December 16, 2025.

Chair Kiley, Ranking Member Bonamici, and Members of the Committee,

Thank you for inviting me to testify before the committee today on the crisis in youth sports and the impact on our children, communities and nation. My name is Tom Farrey and I am founder and director of the Aspen Institute’s Sports & Society Program, the mission of which is to convene leaders, facilitate dialogue and inspire solutions that can help sport serve the public interest. Our signature initiative is Project Play, which develops insights, ideas and opportunities to build healthy children and communities through sports.

We started at the base of our disjointed U.S. sports ecosystem. In 2015, Project Play released the nation’s first framework to provide all youth through age 17 access to safe, quality, affordable sport activity. A resource aggregating the most promising opportunities to emerge from two years of roundtables with 300+ leaders, “Sport for All, Play for Life: A Playbook to Get Every Kid in the Game” offers a unifying model anchored in the values of development, with eight strategies for the eight sectors that touch the lives of children.

The framework quickly became one of the most-read reports ever produced by the Aspen Institute, making Project Play one of its most prominent, respected, and influential domestic initiatives.

Since then:

20,000+ leaders from the sport, health, education, media, philanthropy and tech sectors have joined our network, seeking guidance and learnings from our work.

ESPN, NBC Sports, NBA, MLB, US Tennis Association and other sports leagues and national bodies have launched or shaped symbiotic initiatives. With our partners and Kobe Bryant, we created the largest media campaign in the history of youth sports, #DontRETIREKid, which won 37 national and international awards.

We’ve helped 16 states, counties and cities develop original research and recommendations that empower local leaders to grow access to sport. Community foundations have reorganized their grant-making, guided by our strategies. More than $140M in funding from philanthropy, business and government has been unlocked for local sport providers. New York became the first state to legalize sports betting with a cut for youth sports, an Aspen Institute idea.

Our program created free resources for parents, coaches and sport administrators. We also introduced the first-ever playbook for principals and school sports leaders, aggregating the most innovative ideas from school sports programs around the U.S.

Project Play staff and ideas helped shape the U.S. federal government’s first-ever National Youth Sports Strategy. And with our guidance, the private-sector National Physical Activity Plan added its first-ever recommendations for the sports sector.

Data and insights from surveys which we commission for parents, coaches and youth are cited by the national media, shaping public discourse on youth sports.

We have established the nation’s premier annual vehicles to convene stakeholders to take measure of and push forward the movement — the Project Play Summit and State of Play report. Our State of Play 2025 report was released today, identifying trends in participation, coaching and other topics of interest to stakeholders.

We now serve as field catalyst at each level of the largest youth sport system in the world:

Local/community: We develop comprehensive State of Play reports that help unlock and shape grantmaking, policies and new partnerships, creating the conditions for Collective Impact. Just one example: In 2021, we partnered with the foundation of NBA superstar Stephen Curry to landscape the state of play across the city of Oakland. Since then, the foundation has worked with local partners to lift participation in middle school sports from 17 percent to 62 percent.

State: We connect silos across stakeholder organizations in Colorado, via Project Play Colorado, where youth sport participation rates have grown in recent years and have the capacity to grow further through collaboration and shared agendas.

National: We convene and partner with dozens of leading organizations in sports, tech and media, education, public health, and community recreation to share knowledge and drive action. Today, as a companion to the national State of Play report, we released the 2025 impact report of our 63X30 national roundtable, comprised of 20 organizations committed to act meaningfully in support of our call to help the nation get 63 percent of youth playing sports by 2030. In the past year alone, the roundtable trained more than 263,000 coaches, engaged 3.5 million parents, and invested more than $71 million in youth sport access, safety, and infrastructure.

In sum, Project Play has established itself as the non-government, non-partisan engine to reimagine youth and school sports in America — in their best form. By developing insights, ideas, and opportunities with our network of networks, we have helped lay the groundwork to make healthy sport activity accessible to all, regardless of zip code or ability.

Collectively, as a nation, we’re making progress. The latest data from the National Survey of Children’s Health, via the U.S. Census Bureau, shows that 55.4 percent of youth ages 6-17 played organized sports in some form in 2023, That’s up from just over 49 percent in 2021 as the nation emerged from COVID. We have prevented what happened during the last major societal disruption, the 2009 economic crisis which gutted municipal budgets and sport programs.

Still, the nation is behind where it was in 2016 when the government first started collecting data through this instrument — and 58.6 percent of youth played sports. That’s when an inter-agency group working through Healthy People 2030, our nation’s public health objectives, set the target of 63.3 percent of youth playing sports (a 10 percent lift) by the end of this decade.

Now, a host of new pressures on being brought to bear on the games that children play:

Private equity, which is flooding into the space, chasing the more than $40 billion a year that families alone are spending — more cash than ever is flowing through college sports, the NFL or any professional league in the world. They’re buying up clubs and facilities and software companies that register the 30 million or so youth who play.

Technology, which is turning kids into content from moment they slip on a uniform. Advances in streaming technology mean that some kids today will have nearly every moment of their sports journey captured on video, via apps. Artificial intelligence will cut up that video into highlights, and some adult will monetize those highlights — might YouTube, might be the tournament organizer, might be their parent.

Youth sport tourism, the investments made by cities and counties into the construction of vast, so-called “mega-cilities” with lots of fields and gyms that are designed for tournaments that draw families from out of the area and into hotel rooms that can support municipal budgets. Want to get the most heads in beds? Host an AAU national basketball championship tournament for second graders (yes, such a thing exists) because you’re more likely to get the whole family to come. And you can charge each of them a fee to park their car and enter the gym where their seven-year-old chucks balls from their hip under the scrutiny of bellicose parents. Outside of Orlando, there’s a youth sports site being built that costs $1 billion.

And NIL, otherwise known as sponsor dollars. You think what’s happening in college sports is madness? Look downstream to middle school athletes, some of whom — a select but influential few — now can make millions not long after they hit puberty. With no legal guardrails that ensure they won’t be exploited by adults.

To be clear, none of these developments are necessarily or at least automatically bad. In a commercialized landscape, athletes who create value should derive value. Most of us would argue that capitalism is good, and technological innovation no less so. But we want sports to remain an exercise in transformation — of the child — and not just transaction. We need to protect against the inertia of a market-based economy when it seeks to turn children into yet another opportunity to, first and foremost, make a buck.

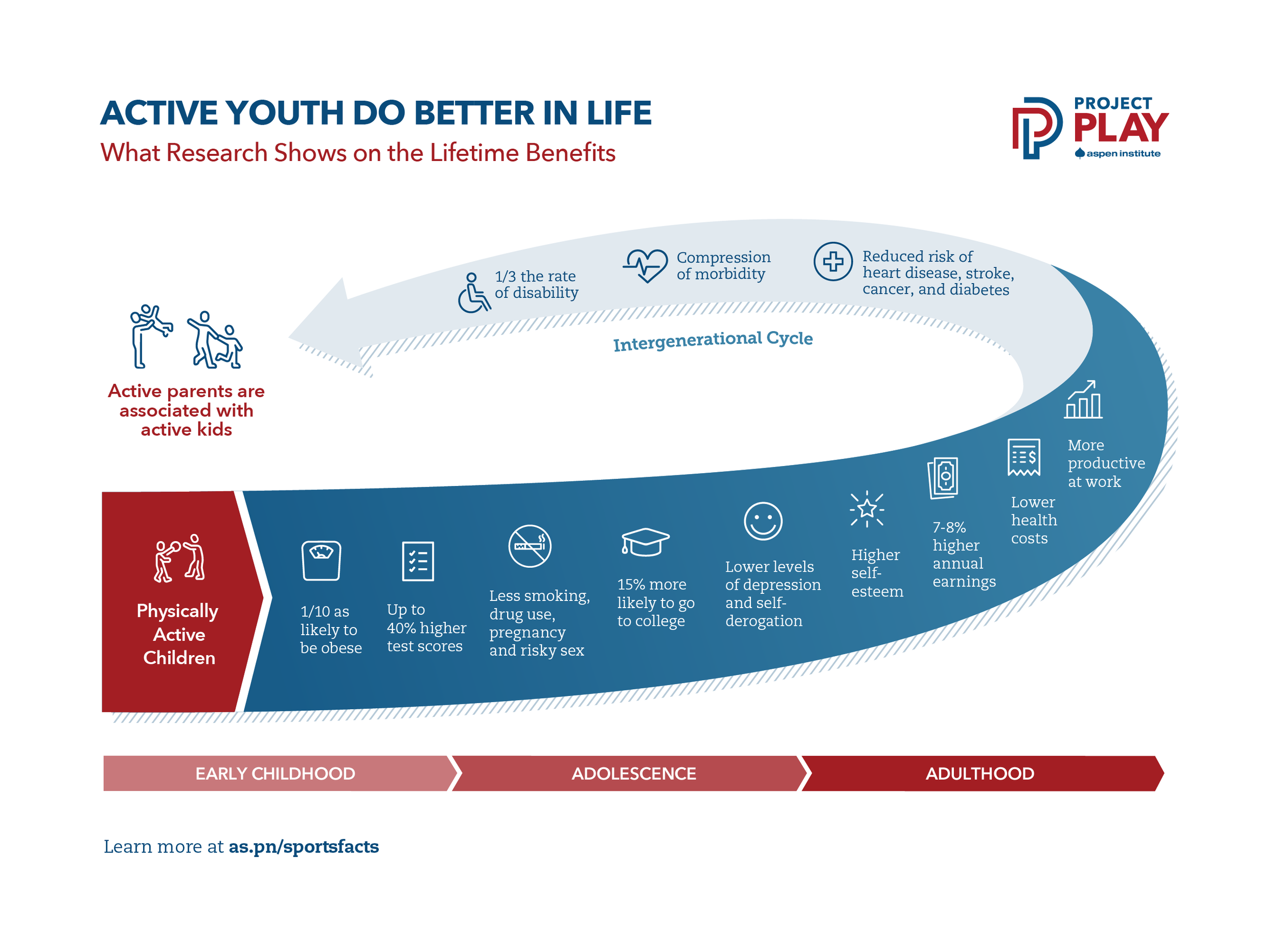

Sport is just too valuable of a social institution for that. Consider what the research says about the benefits that flow to children whose bodies stay in motion through adolescence:

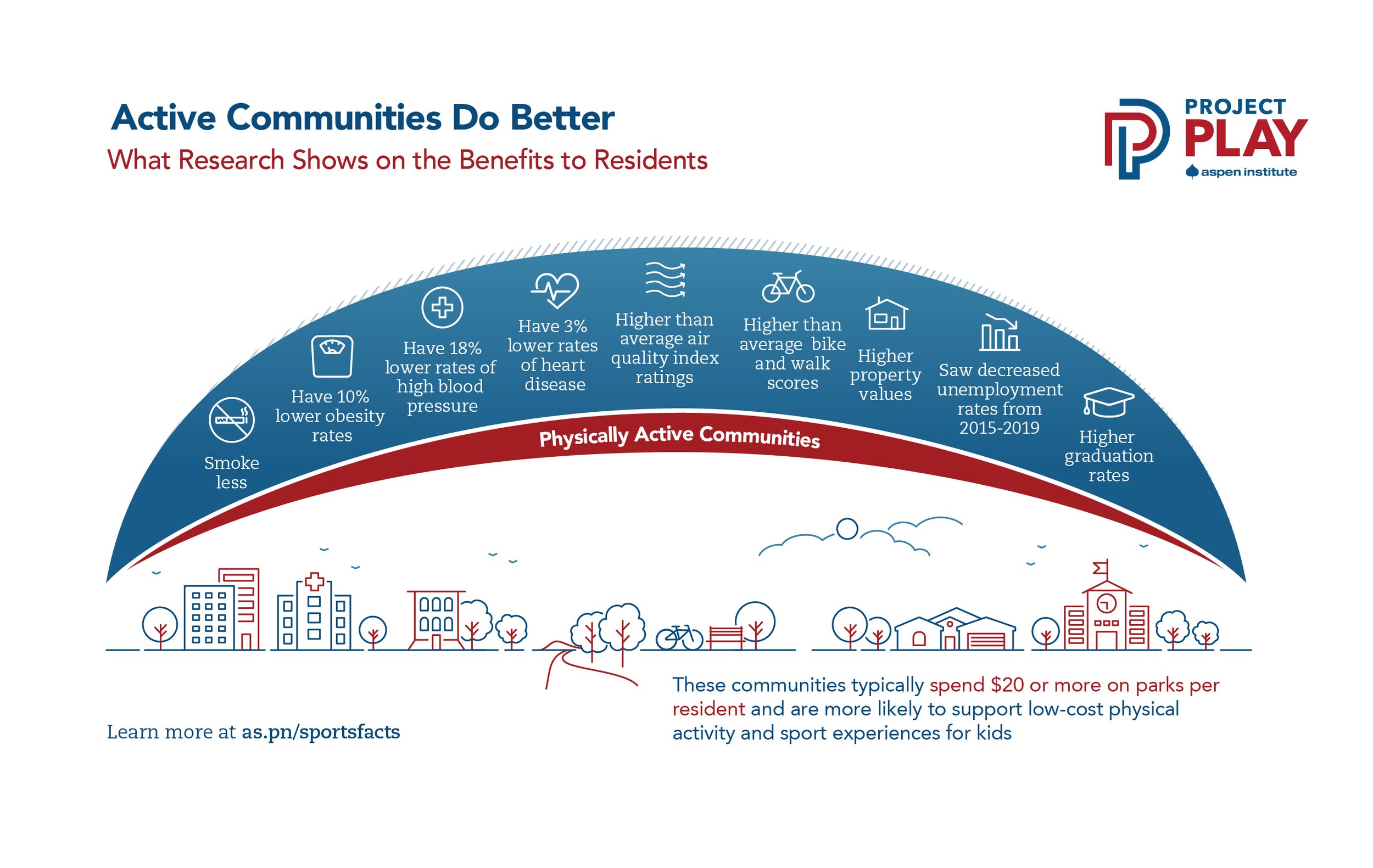

Consider the benefits that flow to communities:

The mental and physical health benefits of playing sports are profound. Reaching the federal government target of 63 percent participation could deliver more than 1.8 million Quality Years of Life, plus a $80 billion in societal benefits from direct medical costs saved and greater worker productivity, according to a study published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine by researchers from the Institute, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and leading universities.

This is the real value proposition for youth sports. It’s the child who falls in love with sports, moves their body, and learns teamwork and resilience — skills that will propel them as they move into adulthood. It’s the games and practices that take the cell phone out of kids’ hands for a couple hours at time. It’s the ability to compete within the rules of a game — the rule of law — and respect those on the other side as opponents, not enemies.

Chairman Kiley and members of this subcommittee, I want to commend you for calling this hearing, the first that I’m aware of that addresses youth sports in a direct way. Congress has held plenty of hearings on college sports, plenty of hearings on Olympic sports. This — youth sports — is the largest and most important layer of our sport ecosystem, the layer that American families care about the most. Because once you have a child, your favorite athlete is no longer LeBron James or Bryson DeChambeau — it’s the kid down the hallway. That’s the athlete you invest the most in, emotionally and financially. That’s who you most want to succeed on the field and in life. That’s who you want to have an opportunity to play. And that’s who your constituents want you to support, most of all. Surveys bear out this fact. Three years ago, the Aspen Institute served as fiscal agent for the Commission on the State of U.S. Olympics and Paralympics that was set up by Congress. In a survey for that commission, more than half of U.S. adults (52 percent) said taxpayer support for sports would have the greatest impact at the youth and school sports levels. The other levels received much smaller numbers: The Olympics (14 percent), Paralympic Games (7 percent), college sports (6 percent) and professional leagues (5 percent).

In calling this hearing, you recognize what Teddy Roosevelt and the original promoters of youth sports and recreation figured out at the start of the 20th century — that sport is a tool of nation-building and personal development. President Roosevelt used the White House pulpit to promote boxing, football and sport overall as a tool of masculinity and toughness. Muscular Christians saw sport as an agent of moral and health development, so they invented games like basketball and volleyball. At the time, an era of colonial expansion, we were fighting wars around the world, and military recruiters viewed sport as a way to build soldiers. Titans of industry like the Carnegies and Rockefellers saw sport as a model and training ground for American competitiveness, with its sorting of winners and losers.

Interscholastic sports. The Playground Movement that got thousands of parks built in the first couple decades of the 20th Century and got many adolescents off of urban streets. The introduction and growth of physical education classes in schools. All of this helped us build our economy, fight wars, and create a sense of belonging and freedom in our society.

Indeed, if the 20th century was the American Century, then I would argue that in no small way that youth and school sports helped make that happen. It’s why we now see China investing significantly in PE and sports like basketball and soccer, building facilities and requiring students to pass fitness tests in order to advance to universities. It’s why we see Saudi Arabia building entire cities with an eye toward sport for all. They know sports works.

To compete globally, we need to up our game. And that starts with a clear-eyed view of the moment, the barriers to entry that sideline nearly half of all kids and adolescents today.

That begins with:

The Cost Crisis in Youth Sports

Across nearly every sport, the cost of participation has skyrocketed — 46 percent since 2019, according to Project Play research. What used to cost a family a small seasonal fee now runs an average of $1,016 for registration, equipment and other expenses, our 2024 survey of sports parents found. Families with adolescents playing club sports often pay far more, sometimes $10,000 or more with travel.

This is creating a two-tiered system of access:

kids whose families can afford to play, and

kids whose families cannot.

Then there’s the time ask — the average parent spends more than three hours a day on their child’s sport activities — planning, driving, watching, washing, traveling for practices and games, according to our research.

The result is predictable: high attrition rates, uneven access, and lost opportunity — particularly for children in low-income, rural, and minority communities. In the Olympic reform commission survey, half of Americans who played youth sports or who have children who have played said they have struggled to afford the costs to participate. The issue impacts a broad swath of Americans of all backgrounds, including 66 percent who are Latino/a, 62 percent of 35-49-year-olds, 58 percent of those with high school educations, 57 percent of lower-income adults, and 56 percent of Republicans, and 56 percent of those who rent their homes. More than 4 in 5 Americans say sports should be more accessible to those in underserved communities, as well as for athletes with physical disabilities.

And for youth whose parents can afford to underwrite a decade in the youth sports arms race? We see growing pressure to perform at levels that justify their family’s investment and rising rates of overuse and other serious injuries. Since 2007, teenage athletes have experienced a 26 percent rise in ACL injuries, which can limit movement abilities into adulthood.

Fox News coverage of “Benched” hearing, December 16, 2025. Video courtesy House Subcommittee on Early Childhood, Elementary, and Secondary Education.

Fox News coverage of “Benched” hearing, December 16, 2025. Video courtesy House Subcommittee on Early Childhood, Elementary, and Secondary Education.

The Rise of the Commercial Ecosystem

Part of the cost crisis stems from the dramatic growth of the for-profit youth sports industry. Youth sports now generate tens of billions of dollars annually. Much of this revenue is pulled out of communities and families, rather than being reinvested into coaching education, safety programs, facility access, or reduced fees.

For-profit operators are not inherently bad actors — many provide valuable services. But the rapid expansion of commercialized programming has created systemic problems:

Price Inflation: Families effectively subsidize private companies extracting profit from what used to be community-based sport.

Perverse Incentives: Business models depend on more tournaments, more travel, more specialization — often at the expense of child well-being.

Resource Drain: Dollars that could sustain local recreation leagues, school programs, and community coaching are instead flowing to private operators who are under no obligation to reinvest.

We must ask a basic question: Is the youth sports ecosystem designed to serve children, or to serve those making money off children?

Governance Failures in the Non-Profit Youth Sports Space

At the same time, we must be honest about governance challenges within the non-profit sector as well.

Many local youth sports organizations operate as isolated fiefdoms with:

minimal transparency,

inconsistent financial oversight,

weak or outdated governance structures, and

limited accountability to the families they serve.

Meanwhile, some organizations masquerade as non-profits while operating like for-profit enterprises —charging high fees, restricting access, and reinvesting little back into development. That’s not true in every case of course, as there are many good sport providers who have the best interests of children in mind. But many simply specialize in poaching and aggregating talent from other clubs, as that’s what the system rewards.

The 1978 Amateur Sports Act represented our nation’s first stab at sports governance. Rather than create a centralized body within the government to coordinate sport activity as is the case in other countries, it outsourced that role to a non-profit corporation, what is now called the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee, and its affiliated National Governing Bodies of Sports. NGBs undergo audits by the USOPC and U.S. Center for Safe Sport, and grassroots providers that are members of these organizations must abide by certain rules — such as coaches passing background checks and SafeSport abuse training. But most youth sport providers are not NGB members and sit outside of the so-called “Olympic Movement.” And even within that umbrella, NGBs struggle to hold affiliated organizations accountable to best practices in athletic development or program service. This dual failure — unregulated commercial extraction and inadequate nonprofit governance — has created a fragmented, uneven, and increasingly predatory landscape.

Witnesses, L-R: Tom Farrey (Aspen Institute), Steve Boyle (2-4-1 Sports), Katherine Van Dyck (consumer advocate), and John O’Sullivan (Changing the Game Project). Photo: House Subcommittee on Early Childhood, Elementary, and Secondary Education.

What Reform Should Look Like

Reform must be comprehensive, bold, and grounded in the principle that youth sports exist for the benefit of children — not for the enrichment of adults or the protection of entrenched interests.

Congress has an opportunity to address the systemic vulnerabilities that allow financial exploitation, uneven access, and governance failures to persist.

I encourage consideration of the following areas:

Full Transparency and Oversight of Non-Profit Youth Sports Organizations

To protect families and restore trust, Congress should consider:

Mandatory financial transparency for any youth sports organization claiming non-profit status, including public disclosure of revenues, expenditures, executive compensation, and use of proceeds.

Clear board governance standards, including term limits, conflict-of-interest disclosures, and minimum requirements for independent directors.

Accountability mechanisms tied to tax-exempt status for organizations that fail to meet baseline governance expectations.

Investigation of National Governing Bodies (NGBs) for Structural Risk

Non-profit status alone does not guarantee integrity. The Olympic and grassroots sports system includes NGBs and regional affiliates with layered 501(c)(3) structures that can obscure financial flows, shelter profiteering, and complicate oversight.

Reform should include:

Systematic review of each NGB’s corporate structure, including subsidiaries, affiliates, regional bodies, and any arrangements that could mask conflicts of interest or divert funds from athlete development.

Independent conflict-of-interest audits to determine whether decision-makers are benefiting — directly or indirectly — from programs, vendors, or events under their oversight.

Greater transparency obligations regarding partnerships, event ownership, related-party transactions, and vendor relationships.

NGBs should be held to the highest possible standard — not because they are failing, but because children and families deserve a system protected from structural vulnerabilities.

Guardrails for the For-Profit Youth Sports Industry

Congress should consider establishing reasonable safeguards that ensure families are protected from predatory practices:

Clear fee transparency

Consumer protection standards

Transparency of ownership and profit structures

Limits on coercive or misleading program requirements

Oversight of models that push extreme travel or early specialization

These measures don’t stifle innovation — they ensure fairness.

Incentives for Community-Based, Low-Cost Participation

To counteract rising costs and commercialization, Congress should consider:

Federal grants or matching funds to municipalities, schools, and non-profits offering affordable programming

Tax incentives for facilities providing low-cost access

Support for shared-use agreements reducing barriers to gym and field access

Access begins with affordability.

Investment in Coaching, Safety, and Athlete-Centered Development

Reform should strengthen:

Coach education and certification pathways

SafeSport and child-safety standards

Evidence-based training models

Multi-sport developmental pathways

Programs shown to reduce injury, overuse, and burnout

Quality must be a universal expectation — not a privilege.

Strengthened Alignment Between NGBs, SafeSport and Local Providers

NGBs bring expertise, standards, and infrastructure; local programs deliver access and community touchpoints. The ecosystem works best when these efforts reinforce each other.

Congress can help drive stronger alignment through:

Shared accountability frameworks

Consistent safety and training standards

Transparent collaboration requirements between national, regional, and local organizations

Congress should consider requiring any organization providing sports for children to register with the U.S. Center for Safe Sport. That would create minimum common standards related to safety for children, including criminal background checks of and abuse training of coaches. It would also create, for the first time, a national database of organizations serving youth through sport, a mechanism for communicating best practices.

Role of State Governments

Some states are now regulating or proposing the regulation of non-school sport programs. Others are allocating new funding to support programs that serve vulnerable populations, and some legislatures have created sports commissions to recruit events and engage with youth sports stakeholders. At the Project Play Summit in May 2024, Maryland Gov. Wes Moore became the first governor to sign on to the Children’s Bill of Rights in Sports, a set of guiding principles drafted by the Aspen Institute that more than 500 athletes, organizations, counties and cities have endorsed.

Related materials:

Five leading examples: In recent years, some states have begun providing substantial public resources and setting up guardrails for young children involved in organized athletics. The absence of federal regulation and persistent problems with the youth sports ecosystem — low participation rates in poor communities, an epidemic of overuse injuries, and a lack of systematic training or oversight of coaches — have spurred the changes in state behavior. Colorado, Alabama, California, Minnesota and Massachusetts stand out for their leadership in addressing these oversights. Read Aspen Institute Report

How states can support: States have used five levers to address gaps in safety and access in youth sports:

Legislation and regulation;

Funding and support

Partnerships and collaborations;

Education and awareness campaigns; and

Monitoring and oversight.

Download a two-page resource with 20 examples of state actions.

Role of Local Governments

Even at the local level, youth sports is a messy, siloed space. Club and school coaches don’t communicate well with each other. Programs fight for facilities space. Efforts to reach underserved populations are scattershot. Some municipal and county governments have created boards to work through such issues.

Related materials:

Three leading examples: A handful of cities and counties have begun to pay closer attention to how sports in their areas are organized and made available to youth. Some local governments are working to coordinate and rationalize the way sports are offered to children and adolescents in their areas. Others are providing funds to neighborhood youth sports groups. Governments in three communities stand out for their leadership in improving youth sports: Fairfax County, Virginia; Montgomery County, Maryland; and the city of Philadelphia. Read Aspen Institute Report

Five ways cities and counties can support: A two-page resource with five mechanisms local governments can use to increase access and quality in youth sports programs:

Collaboration with schools and sports providers;

Permitting and regulation;

Funding and grants;

Facilities management; and

Community outreach and engagement.

Re-Centering Youth Sports Around Children

We must collectively reaffirm a simple principle: Youth sports exist for children — not for organizations, not for profit, and not for personal fiefdoms.

Every dollar extracted from families must be a dollar invested in development.

Every governance failure erodes trust.

Every child priced out represents a loss we all share.

If we commit to building a youth sports system based on accessibility, accountability, transparency, and reinvestment, then the transformative power of sport — the power we all believe in — will remain within reach for every child, in every community, across this country.

One final, important ask: Please consider the downstream impacts on youth and school sports, the largest layer of our sports ecosystem, when attempting to reform big-time college sports. College sports do not exist in a vacuum — what you decide to do on NIL, player agency and compensation, anti-trust and other topics are policies that will influence incentives, structures and practices that shape access, quality and safety in youth sports.

So, study the potential implications of any policies under consideration, with an eye toward building a youth-centered sport ecosystem that serves all — children, communities, nation.

Thank you for allowing me to share my thoughts on how America can win through sports.

Tom Farrey is the founder and executive director of the Aspen Institute’s Sports & Society Program.